Aging of the immune system

Overview of the latest research on the aging immune system and its relationship with inflammation

Highlights

1 – Aging is a multifactorial process driven by various intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including genomic instability, telomere shortening (DNA sequence changes) [A], epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, impaired macroautophagy, altered nutrient sensing [B], mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, altered intercellular communication, chronic inflammation, and dysbiosis. These factors are closely related to aging, and research has shown that inducing them can accelerate aging, while modifying them can slow, halt, or even reverse the aging process.

2 – Molecules secreted by senescent cells (senescence-associated secretory phenotype SASP [C]) promote chronic inflammation and can induce senescence in normal cells. At the same time, chronic inflammation accelerates the senescence of immune cells, resulting in weakened immune function and the inability to eliminate senescent cells and inflammatory factors, creating a vicious cycle of inflammation and senescence.

3 – Inflammaging [D] (chronic, low-grade, and persistent inflammation) is a recognized hallmark of aging, linked to morbidity and mortality. Inflammaging is so closely intertwined with the aging process that highly accurate aging clocks, predictive of morbidity and mortality, can be constructed using inflammatory markers.

4 – Although coniderable variability in aging exists among individuals, the aging process generally involves chronic inflammation, tissue homeostasis disorders, and dysfunction of the immune system and organ homeostasis disorders, and dysfunction of the immune system and organ functions, functions, readily causing cardiovascular, metabolic, autoimmune, and neurodegenerative diseases associated with aging.

5 – Gerotherapeutic interventions such as caloric restriction, ketogenic diet, or exercise may support healthspan in part by attenuating immune aging through unified immunometabolic mechanisms.

Researches

1 – The immune system offers a window into aging. 2025 Nature Aging.

The immune system permeates and regulates organs and tissues across the body, and has diverse roles beyond pathogen control, including in development, tissue homeostasis and repair. The reshaping of the immune system that occurs during aging is therefore highly consequential.

During aging, the ability of the immune system to efficiently and precisely respond to new antigenic, infectious or neoplastic challenges wanes, and the reactivation and refinement of memory responses falters. One of the earliest manifestations of aging is the involution of the thymus (the site of T cell development), which occurs during puberty. In later life, the immune system increasingly shifts from its homeostatic and protective roles towards a state that is char acterized by heightened proinflammatory activity, with a propensity for autoreactivity. Rather than safeguarding the host, the aged immune system may contribute to systemic dysfunction and pathology.

In this Focus, Nature Aging introduces a series of reviews and opinions that cover recent advances in immune aging. Building on their studies defining immune aging as a driver of organismal aging, Delgado-Pulido and colleagues explore how aging transforms the immune system ‘from healer to saboteur’, and describe the deterioration of protective functions and the acquisition of pathogenic features of the aged adaptive immune system.

Majewska and Krizhanovsky zoom in on one of these protective immune functions that declines with age: namely, the clearance of senescent cells. Through surveying the interactions between senescent and immune cells (which may deteriorate during aging), the authors highlight the role of the aged immune system in facilitating the accumulation and propagation of senescent cells across tissues with age, and thereby fueling tissue dysfunction and disease pathogenesis.

The effects of immune aging on age-related diseases are far-reaching. The fatal consequences of immune aging were demonstrated by impaired infection control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Immune aging has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of non-infectious age-related diseases, including cardiovascular, fibrotic and metabolic diseases, cancer and dementia. Indeed, both peripheral immunity and central neuroinflammation are recognized as contributors to, markers of and potential therapeutic targets in neurodegenerative conditions, and inflammaging is a recognized hallmark of aging linked to morbidity and mortalityrk. Pa and colleagues call attention to resident tissue macrophages as particular culprits of inflammaging and propose that restoring resident tissue macrophages by targeting the niche or myelopoiesis in the bone marrow could attenuate their contribution to tumori- genesis and promote healthy aging.

Inflammaging is so closely intertwined with organismal aging that highly accurate aging clocks, predictive of morbidity and mortality, can be built using markers of inflammation. Tracking individual immune aging trajectories could inform on disease risks as well as contribute to the suits of biological age-predictive biomarkers. However, both aging and the immune system hold considerable complexity and diversity. Franceschi and colleagues survey immune aging clocks through the lens of personalized inflammaging. They highlight that each individual’s unique combination of genetics, lifetime exposures and lifestyle factors results in heterogeneous manifestations of inflammaging, pose that precision measures and interventions should be prioritized, and spotlight a potential role for artificial intelligence in navigating this complexity.

Research on the biological processes of aging is often conducted using model organisms or in vitro models, yet thanks to the ease of access to human blood samples, the immune system offers a window into aging in humans. Immune aging can also be leveraged in clinical trials of aging, by testing the strength of vaccine responses or infection control. Trials that test emerging tech nologies or gerotherapeutic interventions could not only identify strategies to improve immune responses but also stand to inform our understanding of the plasticity of aging in humans and offer important milestones in refining the design of trials conducted with older adults. Discussing strategies to boost immune responses to vaccination in aging, Hofer and colleagues highlight the potential of enhancing vaccines by using gerotherapies to attenuate immune aging.

As well as providing an overview of the hallmarks of immune aging, Kim and Dixit further explore gerotherapeutic interventions, through an immunometabolic lens. They explore how gerotherapeutic interventions such as calorie restriction, ketogenic diet adoption or exercise may sustain healthspan in part through attenuation of immune aging via unified immunometabolic mechanisms. They also highlight adipose as an immunological organ with considerable physiological influence on aging.

Across these articles, the immune system stands out as an early target during aging: the loss of its protective capacities facilitates tissue degeneration and pathology. Weyand and Goronzy, however, highlight the acquisition of autoreactive functions during immune aging, and reflect on recent data that unexpectedly report an increase in autoimmune conditions with age. They propose that autoimmunity during aging constitutes inappropriate immune youthfulness and suggest that wan ing immune activity during aging could be beneficial in calibrating autoreactivity.

As a tractable and targetable window into aging in humans, the aged immune system holds opportunities for translationally valuable discoveries and constitutes a potential broad target to extend healthspan. We are very grateful to the authors and reviewers who have contributed to this issue. Our goal for this Focus has been to stimulate interest and promote cross-pollination of ideas across disciplines. We look forward to supporting immune aging research and sharing exciting findings from this field in the years to come.

References

1. Yousefzadeh, M. J. et al. Nature 594, 100–105 (2021).

2. Desdín-Micó, G. et al. Science 368, 1371–1376 (2020).

3. Bartleson, J. M. et al. Nat. Aging 1, 769–782 (2021).

4. Sarazin, M. et al. Nat. Aging 4, 761–770 (2024).

5. López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. Cell 186, 243–278 (2023).

6. Sayed N. et al. Nat. Aging 1, 598–615 (2021).

7. Conrad N. et al. Lancet 401, 1878–1890 (2023).

The immune system offers a window into aging. Volume 5; Agosto 2025 Nature Aging. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-00948-5

2 – Recent Advances in Aging and Immunosenescence: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Shuaiqi Wang1 . Cell. 2025

Introduction

Population aging is currently one of the major global challenges [1]. With the intensification of population aging, delaying aging and improving the quality of life for elderly people have become important tasks. Aging is a multifactorial process driven by various intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, disabled macroautophagy, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, altered intercellular communication, chronic inflammation, and dysbiosis [2]. These factors are closely related to organismal aging, and research has shown that inducing them can accelerate aging, while intervening in them can slow down, halt, or even reverse the aging process [2]. Thoroughly studying these aging factors to elucidate the mechanisms of aging can help identify interventions to delay aging, such as caloric restriction, nutritional interventions, and gut microbiota transplantation, as well as clinical treatments for aging-related diseases, eases, including senolytics, stem cell therapy, and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory including senolytics, stem cell therapy, and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory treatments.

These approaches can mitigate aging and aging-related diseases, thereby achieving healthy achieving healthy aging and longevity [3–5].

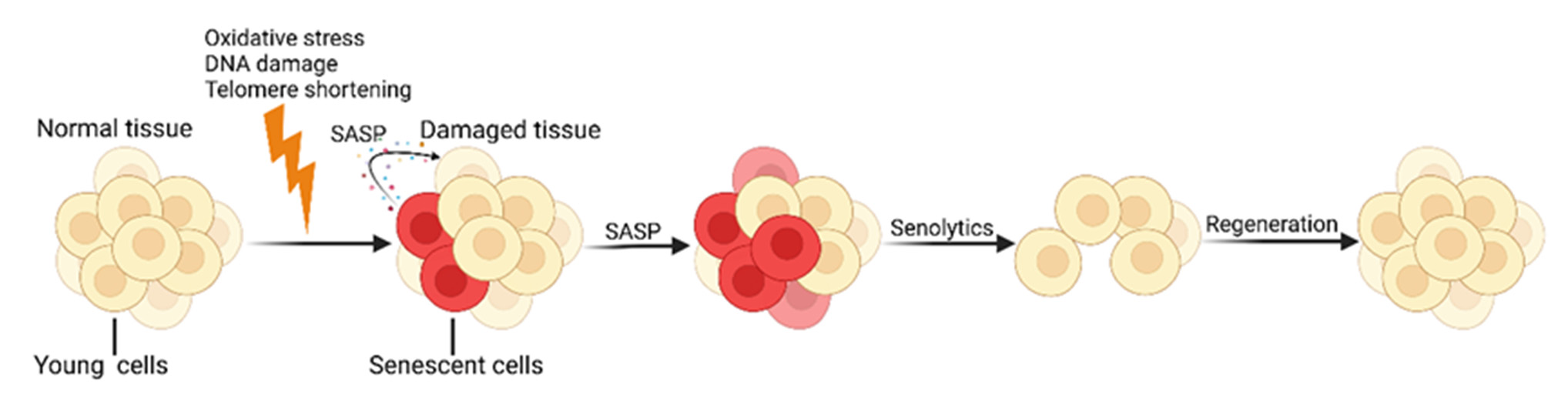

Among these factors, cellular senescence is a key contributor to organismal aging. Targeting senescent cells (SCs) holds promise for developing novel and practical antiaging therapies [6]. Cellular senescence is an irreversible state of cell cycle arrest caused by varivarious factors, such as DNA damage and telomere shortening [7,8]. Additionally, the process whereby immune system function gradually declines or becomes dysregulated whereby immune system function gradually declines or becomes dysregulated with human aging is known as immunosenescence [E] [9]. Although coniderable variability in aging exists among individuals, the aging process generally involves chronic inflammation, tissue homeostasis disorders, and dysfunction of the immune system and organ homeostasis disorders, and dysfunction of the immune system and organ functions, [2] functions, [2] readily causing cardiovascular, metabolic, autoimmune, and neurodegenerative diseases associated with aging [5,10–13]. Existing research indicates that transplanting SCs into young mice induces bodily dysfunction, while transplanting them into aged mice exacerbates aging and increases the risk of death [6].

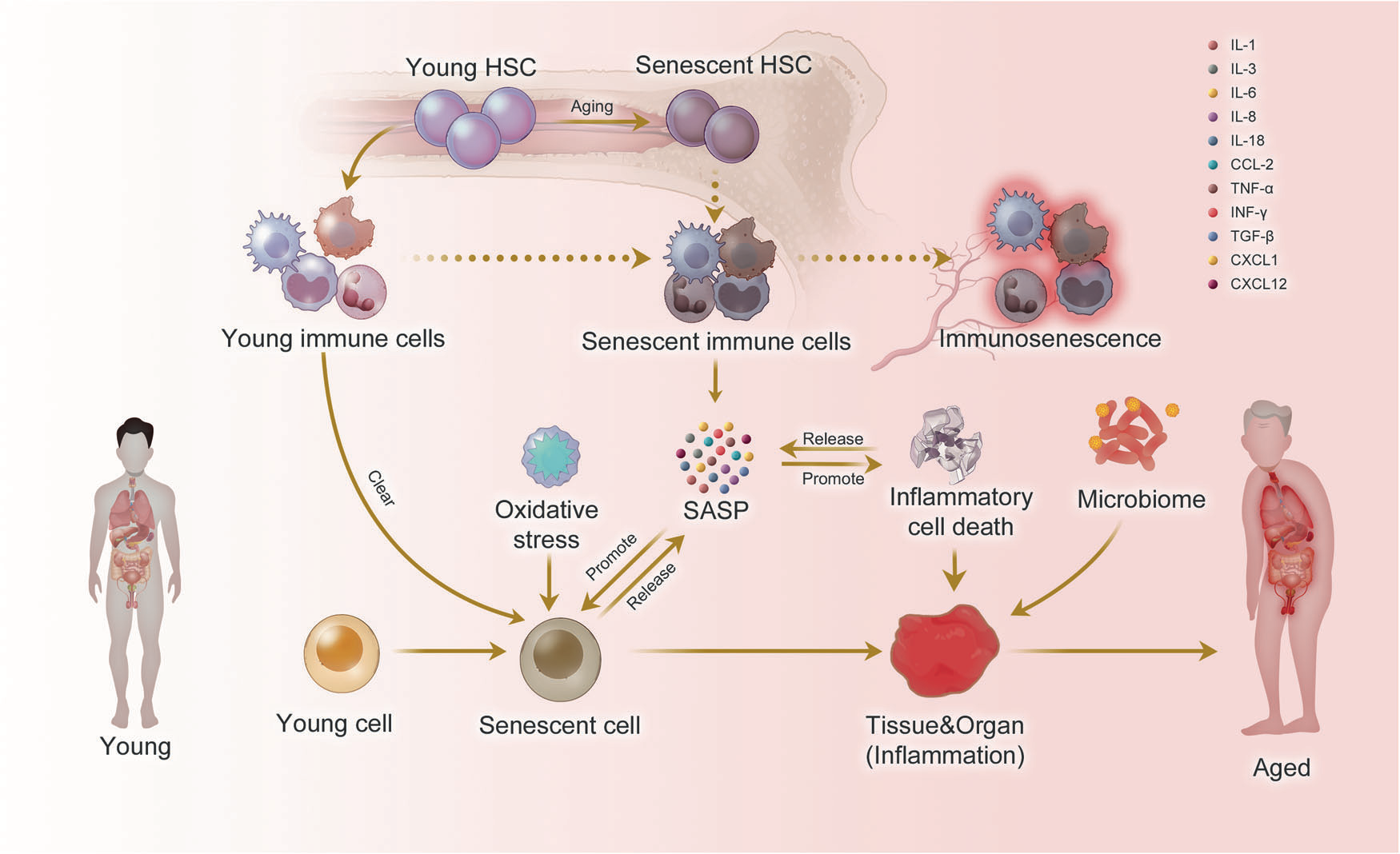

This suggests that SCs accelerate organismal aging. The specific reason is that SCs release the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) into the tissue, promoting chronic inflammation and inducing senescence in surrounding tissue cells and immune cells [14]. SCs and chronic inflammation interact and crosstalk, forming a vicious cycle of inflammation and aging.

Therefore, in-depth research into the key characteristics and underlying mechanisms of cellular senescence, immunosenescence, and inflammation, identifying drug intervention targets, and developing targeted interventions can help mitigate aging and aging-related diseases, thereby promoting healthy aging in the elderly. In recent years, based on the establishment of a series of aging-related cellular and animal models (Table 1), the latest research has revealed the molecular mechanisms of cellular senescence and immunosenescence and the body’s regulation of aging from an immune response perspective.

Moreover, based on new mechanisms, strategies targeting the elimination of SCs have become a promising treatment method for alleviating aging and age-related diseases.

Later, it was discovered that some that small-molecule senolytic senolytic drugs target proteins in cell senescent antiapoptotic pathways (SCAPs) can selectively kill SCs (Figure 1).

Currently, effective, safe, and selective immunotherapy selective approaches targeting SCs are becoming promising a treatment method. Some teams research have teams have already already developed senolytic CAR T cells [19], senolytic vaccines [20], and immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies to achieve the clearance of SCs [21].

Figure 1. 1. Cellular Cellular senescence and senolytics. SCs continuously produce numerous pro-inflammatory senescence and senolytics. SCs continuously produce numerous pro-inflammamolecules and tissue-remodeling molecules, known as the SASP, which further accelerates the aging tory molecules and tissue-remodeling molecules, known as the SASP, which further accelerates the process. Senolytics promote the regeneration of new healthy cells by identifying and clearing SCs. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 10 May 2024).

…….omissis

Summary and Prospects

The global issue of population aging is becoming increasingly severe, with elderly individuals being more susceptible to infections and age-related diseases, leading to higher morbidity and mortality rates [5]. Cellular senescence and immunosenescence are closely linked to aging; therefore, this review focuses on immunotherapies targeting aging. It revisits significant recent discoveries in the mechanisms of cellular senescence and immunosenescence that have propelled the development of new treatment paradigms for aging and age-related diseases.

Recent Advances in Aging and Immunosenescence: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Shuaiqi Wang1 . Cell. 2025

Department of Immunology, CAMS Key Laboratory T-Cell and Cancer Immunotherapy, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and School of Basic Medicine, Peking Union Medical College, State Key Laboratory of Common Mechanism Research for Major Diseases, Beijing 100005, China; b2023005058@pumc.edu.cn (S.W.); huotong1998@pumc.edu.cn (T.H.); b2022005055@student.pumc.edu.cn (M.L.); s2022005053@student.pumc.edu.cn (Y.Z.); zhangjianmin@ibms.pumc.edu.cn (J.Z.). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14070499

3 – Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Brain Structure in the Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults. 2024

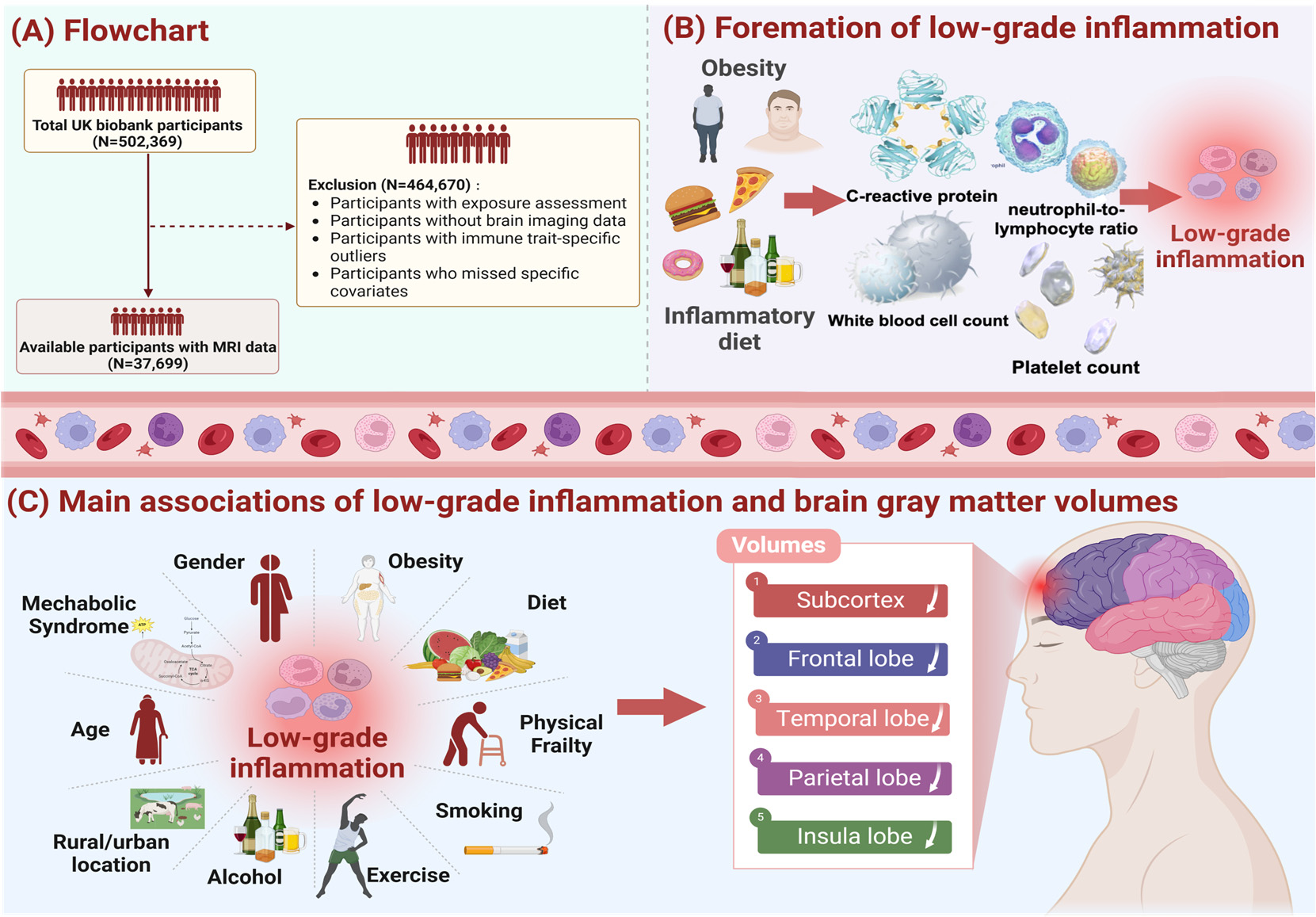

Abstract: Low-grade inflammation (LGI) mainly acted as the mediator of the association of obesity and inflammatory diet with numerous chronic diseases, including neuropsychiatric diseases. However, the evidence about the effect of LGI on brain structure is limited but important, especially in the context of accelerating aging. This study was then designed to close the gap, and we leveraged a total of 37,699 participants from the UK Biobank and utilized inflammation score (INFLA-score) to measure LGI. We built the longitudinal relationships of INFLA-score with brain imaging phenotypes using multiple linear regression models. We further analyzed the interactive effects of specific covariates. The results showed high level inflammation reduced the volumes of the subcortex and cortex, especially the globus pallidus ( β [95% confidence interval] = −0.062 [−0.083, −0.041]), thalamus (−0.053 [−0.073, −0.033]), insula (−0.052 [−0.072, −0.032]), superior temporal gyrus (−0.049 [−0.069, −0.028]), lateral orbitofrontal cortex (−0.047 [−0.068, −0.027]), and others. Most significant effects were observed among urban residents. Furthermore, males and individuals with physical frailty were susceptive to the associations. The study provided potential insights into pathological changes during disease progression and might aid in the development of preventive and control targets in an age-friendly city to promote great health and well-being for sustainable development goals.

Figure 1. Study workflow.Figure 1. Study workflow. We screened 37,699 UK Biobank participants to explore the effects of

We screened 37,699 UK Biobank participants to explore the effects of low-

grade inflammationlow-grade(LGI) oninflammation (LGI) on thd brain system, and the exclusion criteria of our study population

thd brain system, and the exclusion criteria of our study population is

shown in pane (A).is shownAdditionally,in pane we(A).usedAdditionally,the weINFLA-score,used thecharacterizedINFLA-score, bycharacterizedC-reactivebyprotein,C-reactive protein, white blood cell, plateletwhite bloodcounts,cell,andplateletneutrophil-to-lymphocytecounts, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyteratio, to measureratio,andto measurequantifyandthequantify the levels of LGI, and relevantlevels of LGI,informationand relevantas showninformationin paneas shown(B). Asinshownpane (B).inAspaneshown(C),intakingpane (C),influen-taking influential tial factors of LGI intofactorsaccount,of LGIweintofit theaccount,multiplewe fitlinearthe multipleregressionlinearmodelregressioncontrollingmodel forcontrollingcovariatesfor covariates (age, sex, IMD, WHR,(age,healthysex, IMD,lifestyle,WHR, healthyprevalencelifestyle,of hypertension,prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and stroke)

diabetes mellitus and stroke)

and conducted subgroupand conductedanalysis bysubgroupage, sex,analysisWHR,bymetabolicage, sex,syndrome,WHR, metabolicphysicalsyndrome,frailty. Thephysicalmainfrailty. The results demonstratedmaina significantresults demonstratedassociationa ofsignificantLGI withassociationatrophyofofLGIbrainwithregions,atrophy ofincludingbrain regions,sub- including cortex, frontal lobe,subcortex,temporalfrontallobe, parietallobe, temporallobe andlobe,insulaparietallobe.lobe and insula lobe.

…omissis

Conclusions

To sum up, the conceptual and design framework of our investigation is to characterize the associations between LGI and brain imaging phenotypes, thus showing that LGI may lead to subclinical cognitive decline or neuropsychic diseases partly via structural neural pathways. Moreover, our analyses revealed that more significant associations of LGI with the atrophy of brain structure among male or individuals with physical frailty. These findings not only contribute to the evolvement of clinical diagnosis and therapy, but also provide a novel perspective for the development of new preventive strategies, namely, when brain lesions are subclinical and without any apparent clinical sign, inflammatory intervention, such as diet therapy, is an early preventive strategy.

Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Brain Structure in the Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults. Yujia Bao et al. School of Public Health, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China; bubble-y@sjtu.edu.cn (Y.B.); c.cctx@sjtu.edu.cn (X.C.); melody321@sjtu.edu.cn (Y.L.); scp-173@sjtu.edu.cn (S.Y.). Nutrients 2024, 16, 2313. https:// doi.org/10.3390/nu16142313

4 -Immunosenescence: Aging and Immune System Decline. Priyanka Goyani. et al. 2024

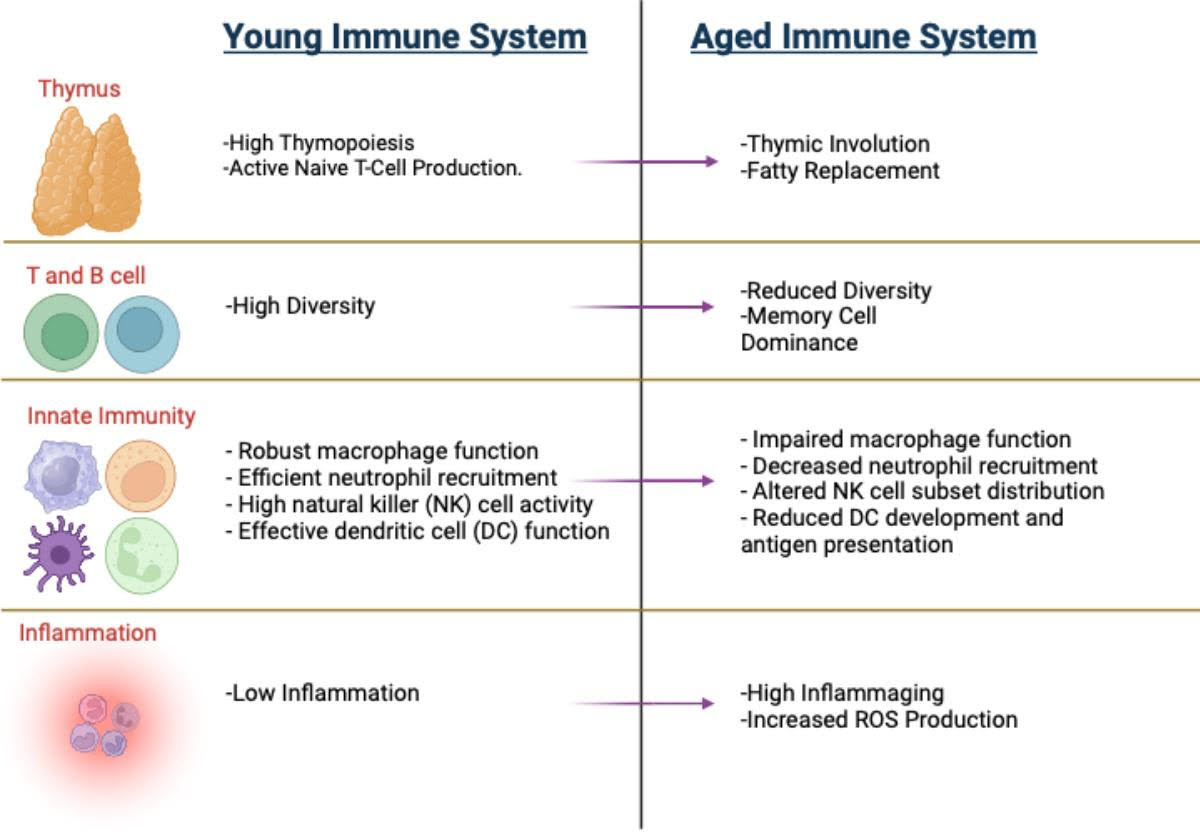

Abstract: Immunosenescence, a systematic reduction in the immune system connected with age, profoundly affects the health and well-being of elderly individuals. This review outlines the hall- mark features of immunosenescence, including thymic involution, inflammaging, cellular metabolic adaptations, and hematopoietic changes, and their impact on immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, T cells, dendritic cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. Thymic involution impairs the immune system’s capacity to react to novel antigens by reducing thymopoiesis and shifting toward memory T cells. Inflammaging, characterized by chronic systemic inflammation, further impairs immune function. Cellular metabolic adaptations and hematopoietic changes alter immune cell function, contributing to a diminished immune response. Developing ways to reduce immunose- nescence and enhance immunological function in the elderly population requires an understanding of these mechanisms.

Immunosenescence is an age-related decline in immune system function that makes people susceptible to autoimmune disorders, cancer, and infections. As the global popula- tion ages, understanding immunosenescence is becoming increasingly important for public health. The immune system’s gradual deterioration is a byproduct of complex interactions between intrinsic cellular aging changes and extrinsic factors.

…..omissis

Conclusion. Immunosenescence negatively affects the health and well-being of older populations by affecting various immune cells (see Figure 4 for comparison of young vs. aged immune systems). The complex interplay between genetic, molecular, and cellular processes plays a crucial role in the aging immune system. Key phenomena such as thymic involution, inflammaging, alterations in metabolic processes, and hematopoiesis underscore the multi- faceted nature of immune decline. These changes result in diminished immune surveillance, reduced vaccine efficacy, and heightened vulnerability to infections and age-related dis- eases, such as cardiovascular diseases, autoimmune diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, cancers, and COVID-19. Comprehensive approaches, including dietary supplementation, lifestyle interventions, pharmacological treatments, and physical activity, may help to manage age-related immune decline and promote healthy aging. By combining these approaches, it may be possible to develop effective strategies for enhancing gastrointesti- nal health, promoting a balanced gut microbiota, and improving immune responses in older adults.

Figure 4. Comparative overview of young and aged immune systems. Key differences between young and aged immune systems. Young immune systems feature high thymopoiesis, naive T cell production, diverse T and B cells, and robust innate immunity. In contrast, aged immune systems exhibit thymic involution, memory cell dominance, impaired innate immunity, and increased inflammation. Immunosenescence: Aging and Immune System Decline. Priyanka Goyani. et al. Department of Biological Sciences, Kean University, Union, NJ 07083, USA; goyanip@kean.edu Department of Radiology, School of Medicine, University of Patras, 265 04 Rio, Greece; up1063080@ac.upatras.gr Correspondence: evassili@kean.edu. © 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Keywords: cytokines; inflammation; immunoscenence; thymus; immune system

5 – Inflammation and aging: signaling pathways and intervention therapies, Xia Li et al. 2023.

Introduction

Aging is characterized by systemic chronic inflammation, which is accompanied by cellular senescence, immunosenescence, organ dysfunction, and age-related diseases. Given the multidimensional complexity of aging, there is an urgent need for a systematic organization of inflammaging through dimensionality reduction. Factors secreted by senescent cells, known as the senescence- associated secretory phenotype (SASP), promote chronic inflammation and can induce senescence in normal cells. At the same time, chronic inflammation accelerates the senescence of immune cells, resulting in weakened immune function and an inability to clear senescent cells and inflammatory factors, which creates a vicious cycle of inflammation and senescence. Persistently elevated inflammation levels in organs such as the bone marrow, liver, and lungs cannot be eliminated in time, leading to organ damage and aging-related diseases. Therefore, inflammation has been recognized as an endogenous factor in aging, and the elimination of inflammation could be a potential strategy for anti-aging. Here we discuss inflammaging at the molecular, cellular, organ, and disease levels, and review current aging models, the implications of cutting-edge single cell technologies, as well as anti-aging strategies. Since preventing and alleviating aging-related diseases and improving the overall quality of life are the ultimate goals of aging research, our review highlights the critical features and potential mechanisms of inflammation and aging, along with the latest developments and future directions in aging research, providing a theoretical foundation for novel and practical anti-aging strategies.

Fig. 1 Inflammaging at the molecular, cellular, and organ levels. During the aging process, almost all cells in the body undergo senescence, a state characterized by a dysfunctional state and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). While immune cells play a crucial role in recognizing and eliminating these senescent cells, they are also affected by SASP, leading to a phenomenon called immunosenescence. Immunosenescence can impair the immunity to respond to infections and diseases, making the organism more vulnerable to illnesses. Moreover, the accumulation of senescent cells can trigger inflammation in organs, leading to organ damage and an increased risk of age- related diseases. This process is exacerbated by positive feedback loops that drive the accumulation of inflammation and organ damage, leading to further inflammation and an even higher risk of aging-related diseases.

Inflammation and aging: signaling pathways and intervention therapies, Xia Li et al. 2023.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01502-8.

Note:

[A] Telomere attrition is the gradual shortening of telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, which occurs with each cell division and is a fundamental process in cellular aging. As telomeres shorten over time and reach a critical length, cells enter replicative senescence, a state where they stop dividing to prevent damage to the genetic code, thereby contributing to age-related diseases and the aging process itself. Telomere attrition is the gradual shortening of telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, which occurs with each cell division and contributes to cellular aging. This shortening triggers a process where cells stop dividing or die (apoptosis) to prevent genetic damage, but it also limits the body’s ability to repair and regenerate tissues, a key aspect of biological aging

[B] Nutrient sensing is the biological process where cells and organisms detect the availability of nutrients like glucose, amino acids, and lipids, initiating adaptive responses to maintain homeostasis and govern metabolism. This process involves specialized biochemical sensors that bind directly or indirectly to nutrients, triggering signaling pathways that control energy production (anabolism) and storage (catabolism) to ensure survival. Key nutrient-sensing pathways include AMPK (activated by energy stress to promote catabolism) and mTOR (activated by nutrient abundance to promote anabolism)

[C] Senescent cells secrete a complex mixture of factors known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which includes pro-inflammatory cytokines (like IL-6), chemokines (like MCPs), growth factors (such as TGF-β and VEGF), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). These factors can promote inflammation, tissue remodeling, and contribute to age-related diseases and cancer progression by altering the surrounding microenvironment.

Components of the SASP

The SASP is a diverse collection of molecules, including:

Cytokines:

These are signaling proteins that mediate inflammation, such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Interleukin-8 (IL-8).

Chemokines:

These attract immune cells to sites of inflammation, including monocyte chemoattractant proteins (MCPs) and macrophage inflammatory proteins.

Growth Factors:

Examples include Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which can influence cell growth and tissue repair.

Proteases:

These are enzymes like Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs), which break down the extracellular matrix, leading to tissue remodeling.

Role of SASP Factors

The SASP plays a significant role in both normal biological processes and disease development:

Physiological roles:

SASP factors contribute to developmental senescence, wound healing, and tissue plasticity.

Pathological effects:

They can drive chronic inflammation (inflammaging), promote fibrosis, and contribute to age-related diseases like atherosclerosis and cancer.

Reinforcing senescence:

The secreted factors create a feedback loop that can reinforce and spread senescence in a process called autocrine and paracrine signaling.

[D] L’inflammaging è un processo di infiammazione cronica, di basso grado e asintomatica che accompagna l’invecchiamento, caratterizzato dall’aumento di molecole infiammatorie che danneggiano progressivamente l’organismo. Questo stato infiammato, non legato a infezioni, contribuisce all’insorgenza di malattie legate all’età, come patologie cardiovascolari e neurodegenerative, e a modificazioni della composizione corporea, come la sarcopenia e l’aumento del tessuto adiposo

Avvertenze:

I numeri tra parentesi quadre si riferiscono alle referenze delle singole ricerche

Back