Human Microbiota and Toxin Metabolism

Abstract

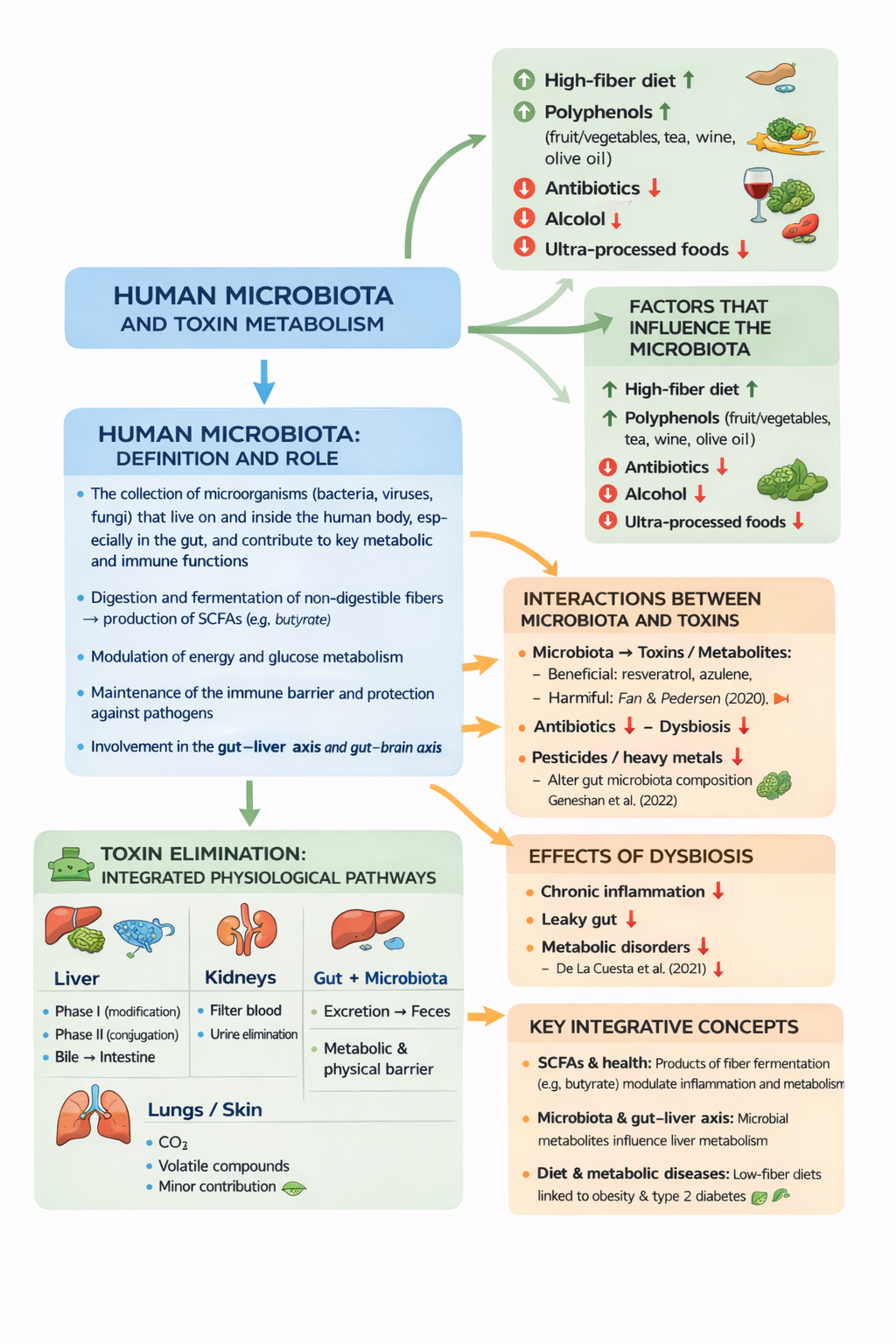

The human gut microbiota is a complex ecosystem of microorganisms that plays a central role in digestion, immune function, metabolic regulation, and the handling of dietary and environmental toxins. Through the fermentation of non-digestible carbohydrates and fibers, gut bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate, which act as key metabolic mediators between the microbiota and the host. These metabolites serve as essential energy substrates for intestinal epithelial cells, support gut barrier integrity, and modulate inflammatory responses and systemic metabolism.

In addition to carbohydrate fermentation, the gut microbiota is involved in the biotransformation of xenobiotics, including environmental toxins, drugs, and food-derived compounds, influencing their bioavailability and toxicity. Conversely, exposure to antibiotics, pollutants, alcohol, and ultra-processed foods can disrupt microbial balance, leading to dysbiosis, increased intestinal permeability, inflammation, and metabolic disorders.

This article explores the bidirectional interactions between the gut microbiota and toxins, the different types of bacterial fermentation (saccharolytic versus proteolytic), and the concept of energetic symbiosis between microbes and the human host. Understanding these mechanisms highlights the crucial role of diet—particularly dietary fiber—in maintaining microbiota functionality, metabolic health, and resilience against toxic and inflammatory challenges.

Keywords

Gut microbiota; Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs); Dietary fiber; Butyrate; Fermentation; Metabolic health; Inflammation; Gut barrier; Dysbiosis; Toxin metabolism; Gut–liver axis; Energetic symbiosis

1) Human microbiota: definition and role

Definition

The human microbiota is the collection of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, and fungi) that live on and within the human body, particularly in the gut, and contribute to critical metabolic and immune functions. (Nature)

Main functions

Digestion and fermentation of non-digestible fibers → production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate. (MDPI)

Modulation of energy and glucose metabolism. (Nature)

Maintenance of the immune barrier and protection against pathogens. (Nature)

Involvement in the gut–liver and gut–brain axes. (Atti dell’Accademia Lancisiana)

2) Interactions between the microbiota and toxins

2A – Microbiota → toxins/metabolites

The microbiota:

Ferments dietary fibers [1], producing beneficial metabolites (SCFAs). (MDPI)

Metabolizes xenobiotics (environmental toxins, drugs, additives), influencing their chemical form and toxicity. (MDPI)

Contributes to the intestinal barrier, limiting the absorption of harmful substances. (Atti dell’Accademia Lancisiana)

Recent research:

1. Fan & Pedersen (2020): link the gut microbiota to the metabolism of food-derived compounds and toxins in humans. (Nature)

2. Tu et al. (2020): review on the microbiome and environmental toxicity (concept of gut microbiome toxicity). (MDPI)

2B – Toxins → microbiota

Some agents negatively impact the microbiota:

Antibiotics → intestinal dysbiosis

Pesticides/heavy metals → alteration of microbial diversity

Alcohol and ultra-processed foods → emerging negative effects

Evidence examples:

Environmental and dietary factors can alter microbial balance and increase inflammation. (ScienceDirect)

2C – Effects of dysbiosis

Dysbiosis (microbiota imbalance) may lead to:

Intestinal inflammation

Increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut)

Metabolic disorders (obesity, insulin resistance)

Recent scientific evidence:

Reviews linking microbiota composition to metabolism and human health. (Nature)

3) Factors influencing the microbiota

Factor

Effect

High-fiber diet

↑ diversity and SCFA production (MDPI)

Polyphenols (fruit/vegetables, tea, wine, olive oil)

Positive modulation of the microbial community

Antibiotics

↓ biodiversity, ↑ dysbiosis

Alcohol

May damage the mucosa and promote permeability

Ultra-processed foods

Associated with dysbiosis (mechanisms still under investigation)

Key research:

1. Charnock & Telle-Hansen (2020): effects of fiber on the microbiota and metabolic health. (MDPI)

2. PubMed reviews (2023–2024): fiber and microbiota modulation with clinical implications in metabolic diseases. (PubMed)

4) Toxin elimination: integrated physiological pathways

Liver

Phase I: structural modification of toxins (oxidation)

Phase II: conjugation → increased solubility

Elimination via bile → intestine

The microbiota may modify these metabolites and influence their recirculation

Kidneys

Filter the blood

Eliminate water-soluble toxins through urine

Intestine + microbiota

Excretion of toxins via feces

Physical and metabolic barrier against the absorption of harmful compounds

Lungs and skin

Elimination of CO₂ and volatile compounds

Minor role in the detoxification of more complex molecules

5) Integrative key concepts

SCFAs and health

Products of bacterial fiber fermentation (e.g., butyrate) not only provide substrates for intestinal cells but also modulate inflammation and systemic metabolism. (MDPI)

Microbiota and the gut–liver axis

Microbial metabolites influence hepatic metabolism, with potential effects on toxin handling and lipid metabolism. (Nature)

Diet and metabolic diseases

Microbiota changes associated with low fiber intake are linked to obesity and type 2 diabetes. (PubMed)

Mini-summary

1. The gut microbiota is an ecosystem of microorganisms that supports digestion, immunity, and metabolism; its alteration (dysbiosis) is associated with metabolic diseases. (Nature)

2. Non-digestible dietary fibers are fermented by gut microbes into beneficial compounds (SCFAs). (MDPI)

3. Microbiota and toxins influence each other: the microbiota can degrade or transform xenobiotics, while substances such as antibiotics and pollutants can alter microbial composition. (MDPI)

4. The body eliminates toxins through the liver, kidneys, intestine (with microbiota involvement), lungs, and skin.

In-depth section “A”: Types of fermentation in the gut microbiota

Gut bacteria mainly ferment non-digestible fibers and complex carbohydrates, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that are beneficial to the host (and not only to the host [1]). However, when protein intake is high or fiber intake is insufficient, protein fermentation may increase, leading to the production of potentially harmful metabolites.

Fiber fermentation (beneficial):

Substrates: dietary fibers, resistant starches, complex carbohydrates

Products: butyrate, acetate, propionate

Effects: nourishment of colonocytes, strengthening of the intestinal barrier, modulation of inflammation and systemic metabolism

Protein fermentation (physiological but potentially harmful if excessive):

Substrates: undigested proteins reaching the colon

Products: ammonia, biogenic amines, hydrogen sulfide, phenolic compounds

Effects: increased intestinal permeability, inflammation, cellular stress, and dysbiosis if predominant

Fats

Fats are not fermented like fibers and carbohydrates, but they strongly influence the microbiota through modulation of bile acids and inflammation. The type of fat consumed (unsaturated vs saturated) contributes to shaping microbial composition.

In summary:

A healthy microbiota is characterized by predominantly saccharolytic (fiber-based) fermentation, whereas excessive protein fermentation reflects a dietary and microbial imbalance.

In-depth section “B”: Bacterial fermentation, carbohydrates, and energy in the microbiota

Intestinal bacterial fermentation does not exclusively involve dietary fibers but generally includes non-digestible carbohydrates and other substrates that reach the colon. It is important to distinguish between carbohydrates that are digested and absorbed by the human body and those that instead become metabolic substrates for the microbiota.

Digestible carbohydrates (such as glucose, sucrose, and refined starches) are absorbed in the small intestine and provide energy directly to the host. In contrast, dietary fibers, resistant starches, and non-digestible complex carbohydrates reach the colon, where they are fermented by gut bacteria.

During fermentation, bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—mainly butyrate, acetate, and propionate—which serve dual energetic and metabolic functions.

Butyrate is the primary energy source for colon epithelial cells (colonocytes), contributing to intestinal barrier maintenance and regulation of local inflammation. Acetate and propionate, on the other hand, are partly absorbed and utilized systemically, contributing to hepatic, lipid, and glucose metabolism.

It is essential to emphasize that fermentation is not only beneficial to the host but also represents the central energy mechanism of the microbiota itself. Gut bacteria are not passive entities: they require energy to maintain their metabolism, produce ATP, grow, and replicate. Fermentable substrates [1] therefore provide energy directly to microorganisms, while the produced metabolites represent the metabolic interface between the microbiota and the human organism.

This relationship can be defined as energetic symbiosis: the microbiota derives energy from dietary substrates unusable by humans, and in return produces metabolites that positively influence intestinal physiology, systemic metabolism, and immune regulation. Disruption of this system—such as through a lack of fermentable fiber—compromises both bacterial metabolism and host benefits.

In-depth section “C”: ATP production in gut bacteria and energetic interaction with the host

Gut bacteria predominantly live under anaerobic conditions and obtain energy through fermentative processes. During the fermentation of non-digestible carbohydrates and dietary fibers, intestinal microorganisms produce ATP for their own metabolism, which is necessary for cellular maintenance, growth, and replication.

Bacterial fermentation is less efficient than aerobic respiration in terms of energy yield, but it represents an essential metabolic strategy in the intestinal environment. In addition to bacterial ATP, this process generates final metabolites, particularly short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate.

Butyrate plays a central role in the microbiota–host interaction: it is the primary energy source for colonocytes, where it is oxidized in mitochondria to produce ATP. This energetic support is fundamental for maintaining the intestinal barrier, regulating inflammation, and preserving epithelial stability.

Acetate and propionate can enter the systemic circulation and contribute to hepatic, lipid, and glucose metabolism. In this way, products of bacterial metabolism directly influence the overall energy balance of the human organism.

This relationship represents a true energetic symbiosis:

the microbiota obtains energy from dietary substrates unusable by humans

the host benefits from the produced metabolites, which support metabolism, intestinal integrity, and immune homeostasis

A reduction in fermentable substrates, as occurs in low-fiber diets, compromises both bacterial metabolism and energy availability for the intestinal epithelium, promoting dysbiosis and metabolic dysfunction.

In summary

Gut bacteria produce ATP (adenosine triphosphate) for their own metabolism through fermentative processes and generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that act as energetic substrates for intestinal cells. In particular, butyrate is used by colonocytes to produce ATP, contributing to intestinal barrier maintenance and modulating inflammatory processes and systemic metabolism.

Clarification of terms

Modulating inflammatory processes means regulating the intensity and duration of inflammation, an essential defense mechanism that can become harmful if chronic.

Modulating systemic metabolism means actively influencing and regulating the chemical processes that convert food into energy throughout the entire organism.

Back