(The Role of Water in Reducing Low-Grade Inflammation and Anti-Inflammatory Foods in Maintaining Physiological Homeostasis*)

(with references to the scientific section)

See: Practical vademecum (Why water helps extinguish inflammation)

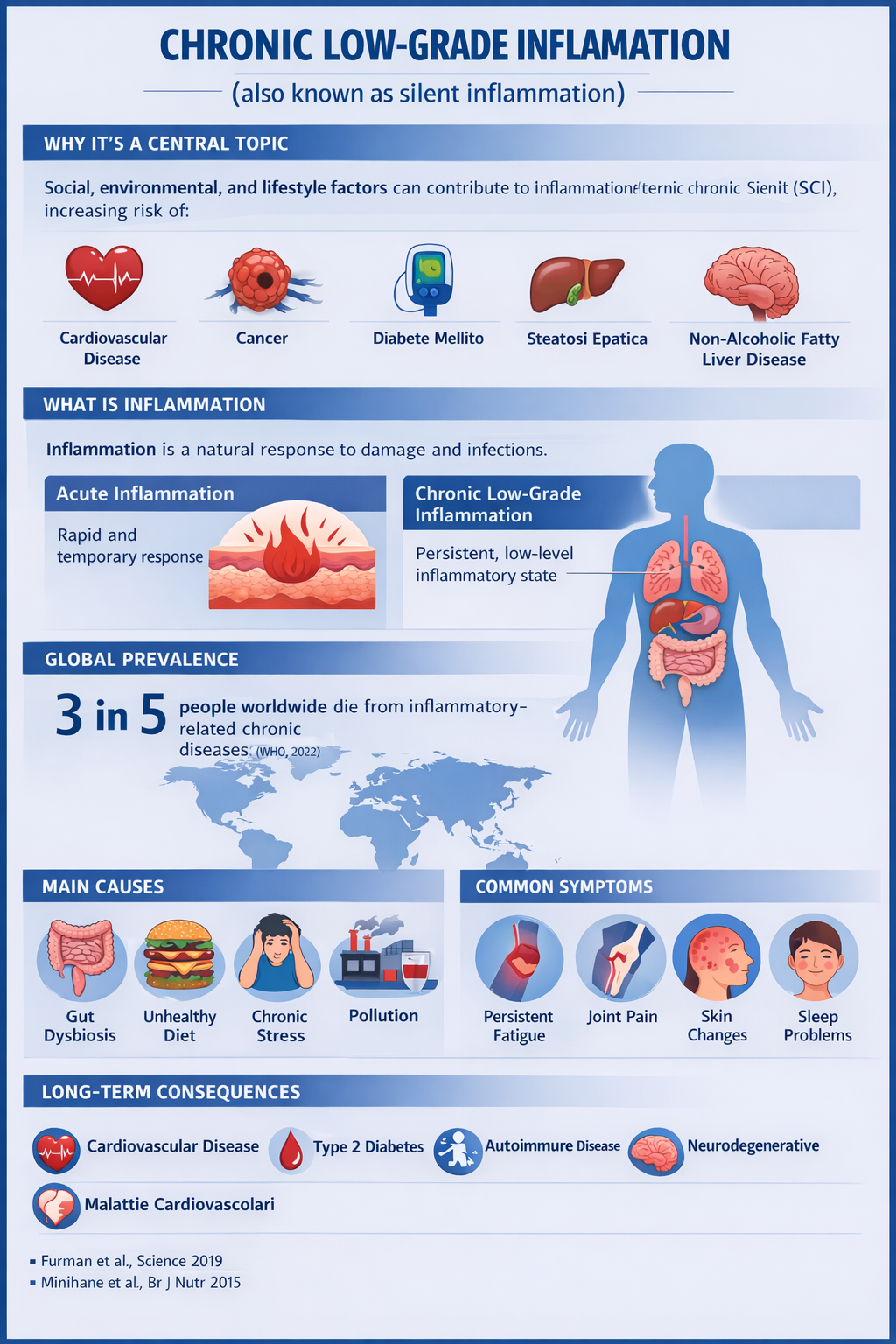

1. Introduction

Low-grade inflammation is a condition of chronic and mild activation of the immune system, associated with numerous metabolic and pathological conditions, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and gut dysbiosis (studiolendaroeflorio.com). Emerging scientific evidence indicates that chronic dehydration and suboptimal dietary patterns are factors that not only affect metabolic function but also contribute to the persistence of a subclinical inflammatory state (PMC).

2. Water as an Essential Nutrient: Physiology and Hydric Homeostasis

Water is the most abundant component of the human body, accounting for approximately 50–65% of body weight in healthy adults (gabrielepelizza.com). This molecule is not merely a solvent but actively participates in metabolic processes, nutrient transport, waste elimination, regulation of cellular volume, and maintenance of body temperature (PMC).

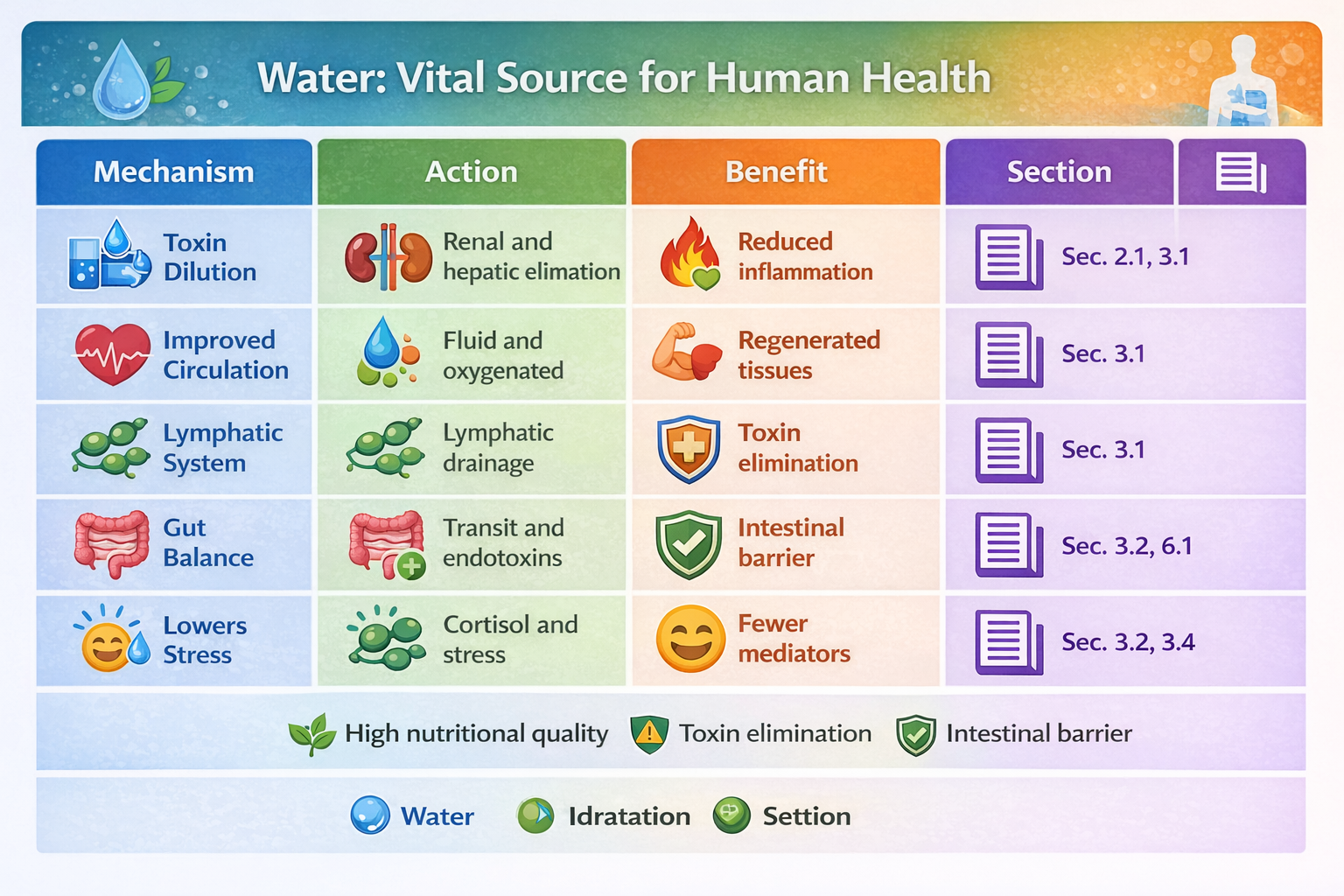

2.1. Transport and Elimination of Metabolic Substances

Water forms the fluid medium in which the following processes occur:

transport of essential nutrients to cells,

mobilization and elimination of metabolic catabolic by-products,

transport of pro-inflammatory mediators to excretory organs (kidneys, liver).

Adequate plasma water volume facilitates glomerular filtration and enhances the kidneys’ ability to eliminate metabolic residues that may stimulate inflammation when accumulated (PMC).

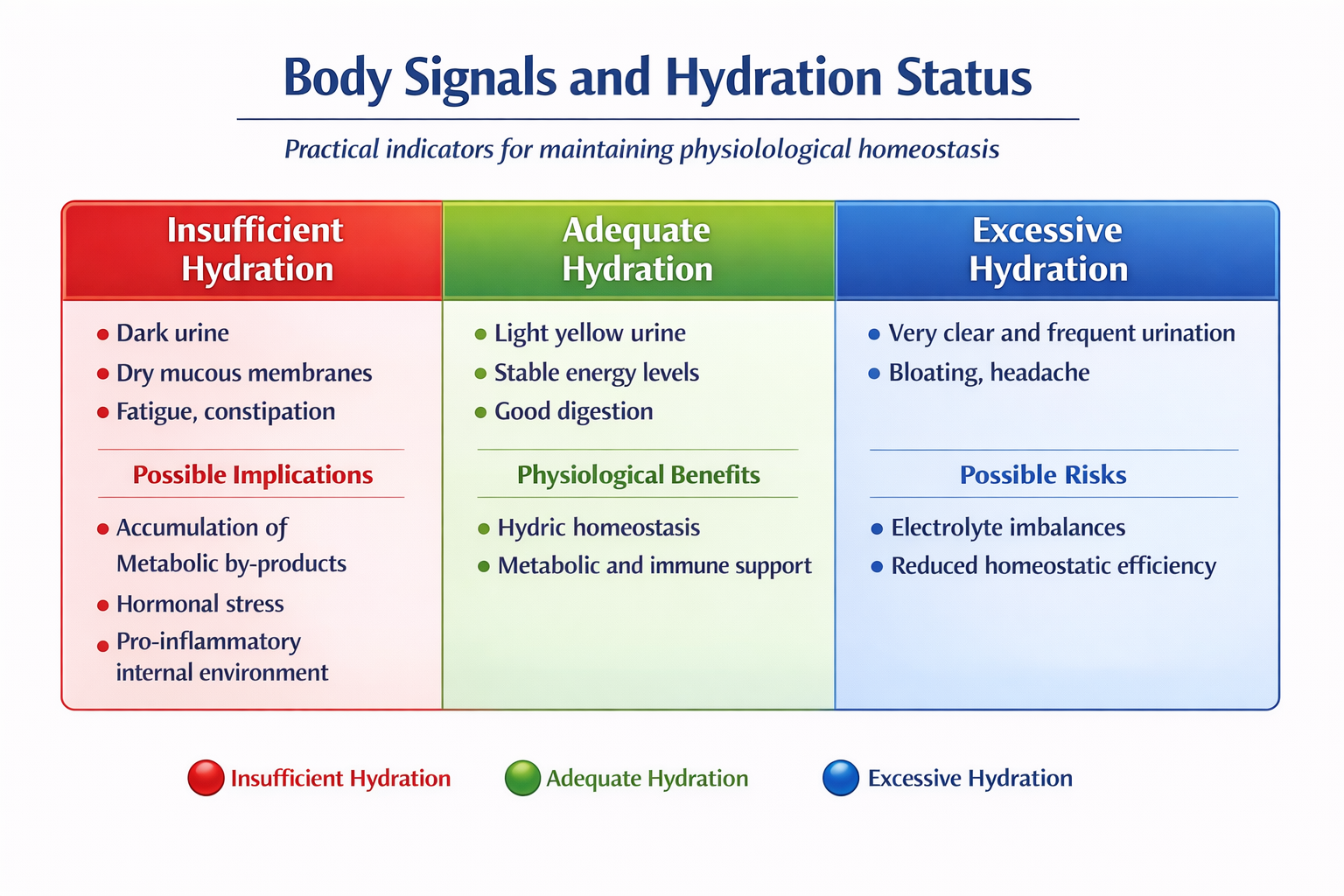

2.2. Hydration and Systemic Inflammation

Studies investigating the effects of water restriction have shown that dehydration can contribute to metabolic imbalances and alterations in cellular function that promote systemic inflammatory responses (PMC).

A recent study on the gut microbiota indicates that water restriction disrupts intestinal homeostasis, leading to a reduction in local immune elements such as Th17 cells—key regulators of mucosal inflammation—suggesting a link between hydration status and immune response (ScienceDirect).

3. Specific Mechanisms Through Which Water Reduces Inflammation

3.1. Improved Circulation and Lymphatic Drainage

Adequate hydration maintains lower blood viscosity, improving fluidity and enhancing the transport of oxygen and nutrients to tissues while facilitating the removal of pro-inflammatory metabolites. Although no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are specifically dedicated to this mechanism, basic cardiovascular physiology clearly describes these effects.

3.2. Effects on the Gut Microbiota

As previously mentioned, recent studies show that limited access to water alters the gut microbiota and reduces key immune cell populations in the colon, highlighting a connection between hydration and intestinal immune regulation (ScienceDirect).

3.3. Hydration and Reduction of Oxidative Stress

Adequate water intake is associated with lower circulating concentrations of free radicals and may reduce systemic inflammatory responses related to oxidative stress, at least indirectly through improved metabolic homeostasis and normal cellular function (limited but suggestive evidence from general clinical reviews) (Prevention).

4. Water as a Support to Immune Response

Hydration also affects general immune parameters. Preliminary evidence suggests that adequate water intake contributes to optimal immune system function, particularly under conditions of physiological stress or high antigenic load (ResearchGate).

5. Anti-Inflammatory Nutrition: Role of Specific Nutrients

An anti-inflammatory diet includes foods rich in:

Polyphenols (berries, green tea),

Omega-3 fatty acids (fatty fish, flaxseeds),

Antioxidants (colorful vegetables, spices such as turmeric and ginger),

Dietary fiber (legumes, vegetables), which nourish the gut microbiota.

These components are associated with measurable reductions in pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and TNF-α in several observational and clinical studies, although the strength of evidence for specific nutrients varies from moderate to weak or preliminary (e.g., polyphenols) (ScienceDirect).

6. Synergy Between Hydration and Anti-Inflammatory Nutrition

The synergy between water intake and anti-inflammatory nutrition is based on two main physiological mechanisms:

6.1. Nutrient Absorption and Bioavailability

Water is the medium in which:

digestion occurs,

chylomicrons are formed and nutrients are transported,

bioactive anti-inflammatory compounds are absorbed.

A well-hydrated intestine promotes optimal transit time, reduces pathological fiber fermentation, and supports a more balanced microbiota, which in turn produces anti-inflammatory metabolites such as butyrate (ScienceDirect).

6.2. Elimination of Inflammatory By-Products

Hydration facilitates the elimination of pro-inflammatory molecules through:

urine (water-soluble metabolites),

bile (certain lipids and metabolic products),

thereby improving the efficiency of the body’s homeostatic response.

7. Clinical and Practical Applications

Although no unified guidelines based on robust RCT evidence exist for anti-inflammatory hydration protocols, physiological principles and emerging evidence suggest that optimal hydration combined with an anti-inflammatory diet may help maintain a favorable physiological state, reduce low-grade inflammation, and support immune homeostasis.

8. Conclusions

Water is a physiologically active element in the modulation of inflammation and maintenance of health, not merely a passive solvent. Its role extends from fluid homeostasis and nutrient transport to regulation of the gut microbiota and immune support.

When combined with a diet rich in anti-inflammatory foods, water acts synergistically to:

improve nutrient absorption,

facilitate the removal of inflammatory mediators,

optimize gut microbiota composition,

support a balanced immune response.

These mechanisms are supported by studies in physiology, microbiology, and emerging research on the effects of hydration on immune modulation.

*Homeostasis is the ability of living organisms to maintain a constant internal environment (temperature, pH, blood sugar, etc.) by self-regulating, despite external variations.

In-Depth Focus: Carbonated Water and Digestion

✅ Potential Benefits

May stimulate digestion

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) mildly stimulates the gastric mucosa, increasing gastric juice secretion.

Helpful in slow digestion

Some individuals find it beneficial after heavy meals.

Promotes satiety

It may help reduce food intake in certain dietary regimens.

⚠️ Potential Discomforts

Bloating and gas

CO₂ is gas and may cause abdominal distension and belching.

May worsen reflux or gastritis

In individuals with gastroesophageal reflux or sensitive stomachs, symptoms may worsen.

Not ideal for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Gas can increase pain and abdominal distension.

Carbonated vs Still Water

Hydration level → equivalent

Digestive tolerance → still water is more neutral and generally better tolerated

General health → no issues if consumed in moderation

How Much to Drink?

For healthy individuals:

Suitable for daily consumption, preferably alternating with still water

Best avoided during meals in those prone to bloating

Summary

Carbonated water is not harmful to health but can influence digestion: it may facilitate digestion in some individuals while causing bloating or gastric discomfort in others. For this reason, alternating it with still water and tailoring consumption to individual digestive tolerance is recommended.

Selected References

Allen, M.D. et al. Suboptimal hydration remodels metabolism…, 2019 (PMC)

Sato, K. et al. Sufficient water intake maintains the gut microbiota…, 2024 (ScienceDirect)

Popkin, B.M. et al. Water, Hydration and Health, 2010 (PMC)

Özkaya, İ. & Yıldız, M. Effect of water consumption on the immune system…, 2021 (ResearchGate)

Clinical trial with anti-inflammatory implications (methodological limitations; further studies needed) (jamanetwork.com)