Gluten HMM subunits importance (update 20-01-2020)

Extract from the study: The structure and properties of gluten

“…..omissis. One group of gluten proteins, the HMM subunits of glutenin, is particularly important in conferring high levels of elasticity (i.e. dough strength). These proteins are present in HMM polymers that are stabilized by disulphide bonds and are considered to form the ‘elastic backbone’ of gluten. However, the glutamine-rich repetitive sequences that comprise the central parts of the HMM subunits also form extensive arrays of interchain hydrogen bonds that may contribute to the elastic properties via a ‘loop and train*’ mechanism. Genetic engineering can be used to manipulate the amount and composition of the HMM subunits, leading to either increased dough strength or to more drastic changes in gluten structure and properties.

….omissis. These properties are usually described as viscoelasticity, with the balance between the extensibility and elasticity determining the end use quality. For example, highly elastic (‘strong’) doughs are required for breadmaking but more extensible doughs are required for making cakes and biscuits. Omisdsis….The grain proteins determine the viscoelastic properties of dough, in particular, the storage proteins that form a network in the dough called gluten (Schofield 1994). Consequently, the gluten proteins have been widely stud ied over a period in excess of 250 year, in order to determine their structures and properties and to provide a basis for manipulating and improving end use quality.

*

…omissis. As a result of the formation of a protein matrix, individual cells of wheat flour contain networks of gluten proteins, which are brought together during dough mix ing. The precise changes that occur in the dough during mixing are still not completely understood, but an increase in dough stiffness occurs that is generally considered to result from ‘optimization’ of protein–protein interactions within the gluten network. In molecular terms, this ‘optimization’ may include some exchange of disulphide bonds as mixing in air, oxygen and nitrogen result in different effects on the sulphydryl and disulphide contents of dough (Tsen & Bushuk 1963; Mecham & Knapp 1966).

….omissis. HMM SUBUNIT STRUCTURE AND GLUTEN ELASTICITY. The HMM subunits are only present in glutenin polymers, particularly in high Mpolymers, the amounts of which are positively correlated with dough strength (Field et al. 1983). This provides support for the genetic evidence (see § 3) that the HMM subunits are the major determinants of dough and gluten elasticity.

Two features of HMM subunit structure may be relevant to their role in glutenin elastomers: the number and distribution of disulphide bonds and the properties and interactions of the repetitive domains. Direct sequence analysis of disulphide-linked peptides released by enzymic digestion of glutenin or gluten fractions has revealed a number of inter and intrachain disulphide bonds involving HMW subunits (Ko¨hler et al. 1991, 1993, 1994; Tao et al. 1992; Keck et al. 1995).

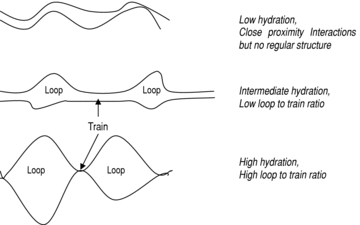

….omissis. Although it is now widely accepted that disulphide-linked glutenin chains provide an ‘elastic backbone’ to gluten, evidence from spectroscopic studies (using NMR and FTIR spectroscopy) of HMM subunits and of model pep- tides based on the repeat motifs suggests that non-covalent hydrogen bonding between glutenin subunits and polymers may also be important (Belton et al. 1994, 1995, 1998; Wellner et al. 1996; Gilbert et al. 2000). These studies have shown that the dry proteins are disordered with little regular structure, but that their mobility increases and β-sheet structures form on hydration. Further changes occur if hydration continues, with a further increase in protein mobility and the formation of turn-like structures at the expense of β-sheet. These observations led to the development of a ‘loop and train*’ model (Belton 1999), which is summarized in figure 6. This proposes that the low hydration state has many protein–protein interactions, via hydrogen bonding of glutamine residues in the β-spiral structures. As the hydration level increases the system is platicized, allowing the orientation of the β-turns in adjacent β-spirals to form structures that resemble an ‘interchain’ β-sheet. Further hydration leads to the breaking of some of the interchain hydrogen bonds in favour of hydrogen bonds between glutamine and water, which then leads to the formation of loop regions. However, it does not result in the complete replacement of interchain hydrogen bonds, and hence solution of the protein, as the number of glutamine residues is high and the statistical likelihood of all the interchain bonds breaking simultaneously is therefore low. The result is an equilibrium between hydrated ‘loop’ regions and hydrogen-bonded ‘chain’ regions, with the ratio between these being dependent on the hydration state.

The equilibrium between ‘loops’ and ‘trains’ may also contribute to the elasticity of glutenin, as an extension of the dough will result in stretching of the ‘loops’ and ‘unzipping’ of the ‘trains’. The resulting formation of extended chains may be a mechanism by which elastic energy is stored in the dough, thus providing an explanation for the increased resistance to extension that occurs during dough mixing. The formation of interchain hydrogen bonds between glutamine residues may also account for the observations that the esterification of glutamine residues results in decreased resistance to extension, while mixing in the presence of deuterium oxide (D2O) rather than water results in increased resistance (Beckwith et al. 1963; Mita & Matsumoto 1981; Bushuk 1998)”. Peter R. Shewry, Nigel G. Halford, Peter S. Beltonand Arthur S. Tatham. From: rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org on May 2011.

La Struttura del glutine e “forza del glutine”

“….omissis. Le glutenine sono proteine polimeriche composte da subunità HMW ad alto peso molecolare (High Molecular Weight, 3-5 molecole diverse per ogni varietà) e da subunità LMW a basso peso molecolare (Low Molecular Weight, da 16 a 25 molecole diverse). Le subunità HMW costituiscono il 10% delle proteine totali, hanno 4-7 residui di cisteina di cui 2-3 localizzati alle estremità della molecola e in grado di formare legami covalenti inter-molecolari (ponti disolfuro) responsabili dell’estrema polimerizzazione del glutine. Le subunità LMW hanno 8 residui di cisteina di cui almeno 2 impegnati in legami inter-molecolari. Le subunità gluteniniche durante le operazioni di impasto si legano tra loro (polimerizzazione) a formare una rete tridimensionale responsabile dell’elasticità (tenacità) del glutine. Le gliadine si legano a questo “scheletro” proteico attraverso legami deboli che conferiscono estensibilità (viscosità) al complesso molecolare del glutine.

….omissis. Ed è proprio questa “polimerizzazione, meglio livello di polimerizzazione” che definisce la forza del glutine la cui “qualità” è misurata con “l’indice di glutine”, in una scala da 0 (scadente) a 100 (ottimo). Ad esempio l’indice di glutine è molto più basso nelle varietà di Strampelli rispetto a quelle di recente costituzione. È interessante notare che il glutine “debole” della varietà Cappelli si accompagna a elevato contenuto proteico delle cariossidi (>14%), a dimostrazione che la “forza” del glutine è dovuta soprattutto alla struttura delle proteine (reticolazione delle proteine) come già detto, piuttosto che alla loro quantità. Infatti, l’incremento dell’indice W negli ultimi decenni è stato ottenuto selezionando nuove varietà con proteine particolarmente elastiche, con un elevato valore di P alveografico”. Le nuove frontiere delle tecnologie alimentari e la celiachia. N. Pogna, L. Gazza 2013.

Note:

A – Il glutine è costituito da due proteine gliadina e glutenina che sono costituite da lunghe sequenze di aminoacidi chiamate peptidi o oligopetidi o polipetidi. La gliadina è costituita dall’unione di circa 100-200 amminoacidi, e la glutenina, costituita dalla combinazione di circa 2.000-20.000 amminoacidi.

B – Legami chimici responsabili della struttura del glutine. I legami chimici responsabili della struttura del glutine sono molto complicati e numerosi, e dipendono dalla differente organizzazione di gliadine (struttura monomerica e globulare) e glutenine (struttura fibrosa e polimerica):

• Legami idrogeno tra i gruppi carichi negativamente delle proteine (ac. glutammico e aspartico) e le molecole d’acqua

• Ponti disolfuro tra i residui di cisteina

• Legami ionici tra i sali e acido glutammico e lisina

• Complessi lipoproteici tra glutenine e lipidi

• Legami elettrostatici tra l’acqua assorbita dall’amido (36%) e residui aminoacidici.

Quando l’impasto è crudo, tutti questi legami non sono stabili, tant’è vero che possiamo modellarlo a nostro piacimento rompendoli e costruendone di nuovi; la loro stabilità viene raggiunta durante la cottura, che comporta la perdita di acqua e l’irrigidimento del reticolo glutinico.

Definizioni

1 – Col termine monomero (dal greco una parte) in chimica si definisce una molecola semplice dotata di gruppi funzionali tali da renderla in grado di combinarsi ricorsivamente con altre molecole (identiche a sé o reattivamente complementari a sé) a formare macromolecole.

2 – Molecola. La più piccola quantità di una sostanza in grado di conservarne la composizione chimica e di determinarne le proprietà e il comportamento chimico e chimico-fisico; può essere costituita da due o più atomi ( m. biatomica, m. triatomica, ecc.), uguali o diversi fra loro; talvolta si parla di m. monoatomica per indicare l’atomo quando si trova in un sistema allo stato libero (per es. nei gas rari).

Deepening: The structure and properties of gluten

Back