This work examines the varietal evolution of durum wheat, from traditional local populations (landraces) to modern cultivars, highlighting the relationship between genetic improvement, agricultural transformation, productivity, and grain quality.

In the earliest historical phase, durum wheat cultivation relied on genetically heterogeneous local populations, well adapted to specific environments but characterized by low yields and high phenotypic variability. With the advent of scientific plant breeding, between the late nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, these populations were progressively replaced by varieties obtained through the selection of pure lines. These new cultivars were more uniform and better suited to mechanization and to the requirements of the processing industry.

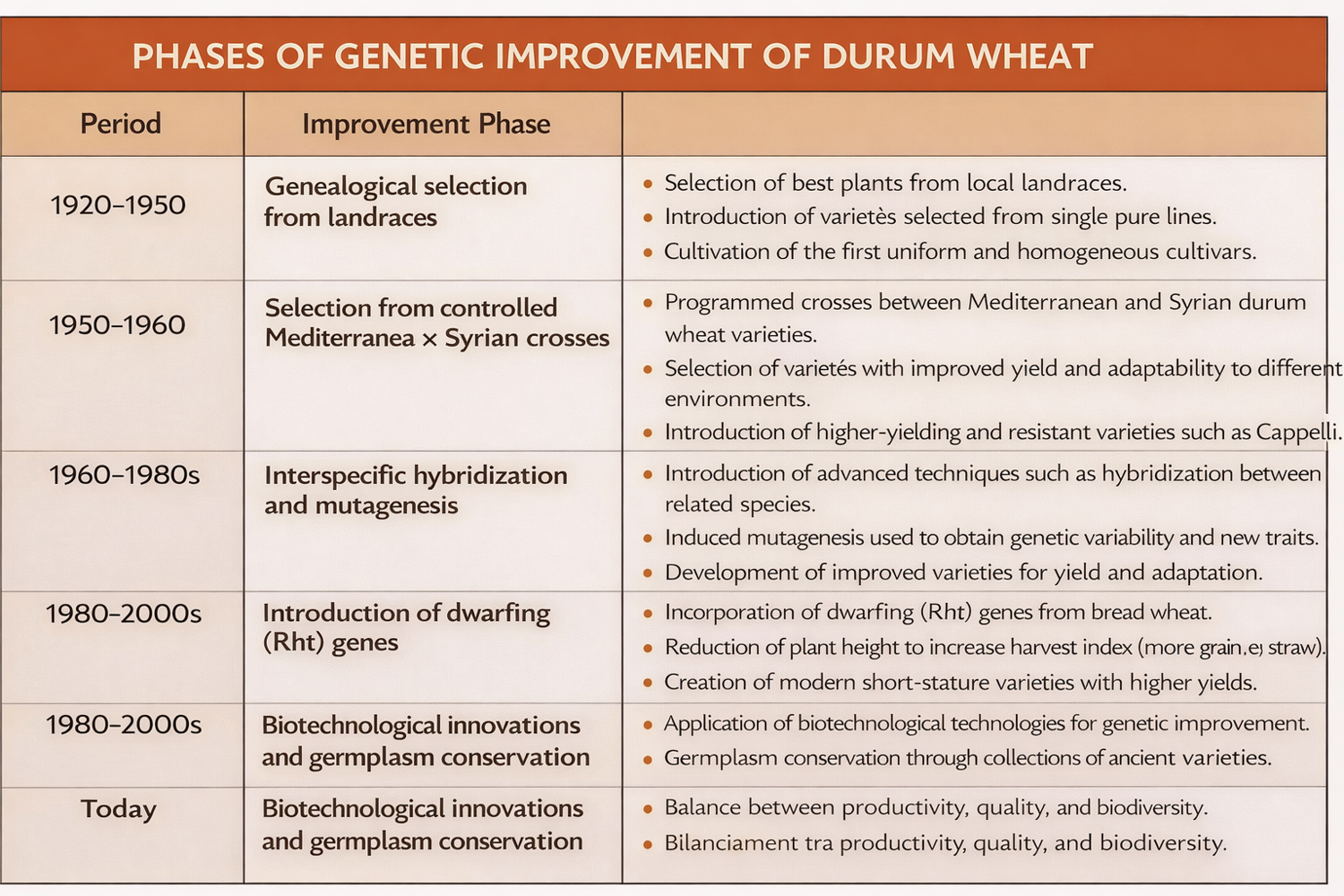

The document describes the main phases of durum wheat genetic improvement in Italy: from genealogical selection based on landraces (1920–1950), to the development of varieties derived from controlled crosses between Mediterranean and Syrian genotypes (1950s–1960s), and subsequently to more advanced approaches such as interspecific hybridization, induced mutagenesis, and the introduction of dwarfing genes (Rht) aimed at reducing plant height and increasing the harvest index.

Particular attention is given to the key role of historical cultivars such as Senatore Cappelli, which for decades represented the benchmark for both productivity and quality in Italian durum wheat, as well as to the later varieties that progressively replaced it due to higher yields and improved resistance to lodging and biotic stresses.

The work also emphasizes that, alongside productivity gains, agricultural intensification and the widespread adoption of genetically uniform cultivars have led to genetic erosion. This makes the conservation of germplasm, through both in situ and ex situ strategies, increasingly important. In conclusion, durum wheat breeding is presented as a dynamic process, closely linked to agronomic innovation, market demands, and the need to balance productivity, quality, and biodiversity conservation. Authors: Rosella Motzo, Francesco Giunta, Simonetta Fois. Coordinator: Prof. Mauro Deidda

Year: 2001. Co-funding body: Banco di Sardegna Foundation (note 1154/4135 of 12/18/2001)

Updates to date (key advances):

1) Reference genome del frumento duro (base per tutte le analisi moderne)

Title: Durum wheat genome highlights past domestication signatures and future improvement targets

Authors: Maccaferri, Harris, Twardziok, et al.

Year: 2019

DOI: 10.1038/s41588-019-0381-3 (PubMed)

Riassunto: Primo riferimento “chiave” con assemblaggio genomico del duro (cv. Svevo) e analisi di diversità/geni target: ha abilitato GWAS più robuste, identificazione di regioni selezionate durante domesticazione/miglioramento e nuovi bersagli per qualità e resa.

2) Speed breeding applicato specificamente al frumento duro (accelerare generazioni + selezione multi-tratto)

Title: Speed breeding for multiple quantitative traits in durum wheat

Authors: Alahmad et al.

Year: 2018

DOI: 10.1186/s13007-018-0302-y (PubMed)

Riassunto: Protocollo sperimentale per velocizzare cicli generazionali e fare selezione precoce su più caratteri quantitativi (non solo uno), utile per accelerare pyramiding di tratti (resa, fenologia, architettura, ecc.).

3) Genomic selection + GWAS in frumento duro (metodi moderni per prevedere resa/qualità)

Title: Genetic dissection of agronomic and quality traits based on association mapping and genomic selection approaches in durum wheat grown in Southern Spain

Authors: Mérida-García et al.

Year: 2019

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211718 (PLOS)

Riassunto: Combina association mapping (GWAS) e genomic selection su tratti agronomici e qualitativi: è un esempio “completo” di pipeline moderna (scoperta di loci + predizione genomica per selezione).

4) Fenotipizzazione ad alta capacità (iperspettrale) per stress caldo/siccità + genetica della resa

Title: High-throughput phenotyping using hyperspectral indicators supports the genetic dissection of yield in durum wheat grown under heat and drought stress

Authors: Mérida-García et al.

Year: 2024

DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1470520 (PubMed)

Riassunto: Porta “novità” sul metodo: usa indicatori iperspettrali come proxy fisiologici per analizzare resa sotto stress, collegandoli alla genetica (utile per selezione in ambienti climate-stress).

5) Genomica + partecipazione agricoltori (local adaptation, “participatory genomics”)

Title: Genomics-driven breeding for local adaptation of durum wheat…

Authors: Gesesse et al.

Year: 2023

DOI: (indicizzato su PubMed; verificabile nella scheda articolo) (PubMed)

Riassunto: Integra dati genomici con selezione/valutazioni degli agricoltori (contesti low-input): introduce un approccio più “real-world” per migliorare adattamento locale e adozione varietale.

6) Dalle landraces agli aplotipi (integrazione “genomic + phenomic” per adattamento climatico)

Title: From landraces to haplotypes, exploiting a genomic and phenomic…

Authors: Palermo et al.

Year: 2024

DOI: (presente nella pagina articolo ScienceDirect) (ScienceDirect)

Riassunto: Usa tecniche avanzate per caratterizzare landraces (es. SSD, dati genomici + fenomici) per trovare materiale “ponte” tra varietà commerciali e resilienza a caldo/siccità.

7) CRISPR in frumento (dimostrazioni di editing multi-gene con impatto su qualità/sicurezza alimentare)

Title: CRISPR-Cas9 Multiplex Editing of the α-Amylase/Trypsin Inhibitor Genes…

Authors: Camerlengo et al.

Year: 2020

DOI: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.00104 (Frontiers)

Riassunto: Esempio di multiplex editing (più geni insieme) per ridurre componenti proteiche potenzialmente problematiche; dimostra velocità/precisione dell’editing rispetto al breeding convenzionale.

8) Protocolli/metodologia CRISPR per wheat (come “toolbox” operativo)

Title: CRISPR-Cas9 Based Genome Editing in Wheat

Authors: Smedley et al.

Year: 2021

DOI: 10.1002/cpz1.65 (currentprotocols.onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

Riassunto: Non è solo “risultato”, ma un riferimento pratico: design sgRNA, costrutti, workflow sperimentale per implementare CRISPR in wheat.

9) Review “stato dell’arte” specifica su duro (trend e metodi emergenti)

Title: Future of durum wheat research and breeding: Insights from early career researchers

Authors: Haugrud et al.

Year: 2024

DOI: 10.1002/tpg2.20453 (acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

Riassunto: Sintesi aggiornata su dove sta andando la ricerca: nuove fonti di variabilità, genomica, fenomica, breeding per stress e qualità, e priorità future.