(In-depth article 6 of: Genetic potential and processing conditions in determining gluten strength, digestibility, and immunogenicity)

In gluten (especially gliadins and, partly, glutenins) there is a strong overlap between:

but the two concepts are not equivalent: resistance is often a facilitating condition, whereas immunogenicity also requires specific rules of immunological recognition.

1) Why many immunogenic sequences are also resistant

The most “problematic” regions of gluten are rich in proline (P) and glutamine (Q). This profile:

-

hampers cleavage by the main human proteases (pepsin, trypsin, chymotrypsin), which have low ability to cut near proline;

-

favors the persistence of long oligopeptides (10–30+ aa) in the intestinal lumen.

This point is well described in reviews and experimental studies on gluten digestion and on the persistence of peptides such as the 33-mer. (Cambridge University Press & Assessment)

2) Why resistance increases the probability of “remaining immunogenic” after digestion

A peptide that resists digestion:

-

remains long enough to contain complete epitopes (or multiple overlapping epitopes);

-

can generate, through partial cleavage, sub-fragments that still retain recognizable sequences.

In other words: it is not just “surviving” digestion, but surviving while maintaining sequence motifs compatible with immune presentation.

Peptidomic/in vitro digestion studies on wheat products show that the residual peptide profile often includes regions known for epitope density and resistance. (ScienceDirect)

3) What makes a peptide truly immunogenic (beyond resistance)

To trigger a T-cell response in celiac disease, a peptide must:

-

be presentable by HLA-DQ2/DQ8 (sequence constraints and “anchor” residues);

-

often become more affine through deamidation by tissue transglutaminase (TG2) (conversion of Q→E in specific contexts);

-

be recognized by specific T cells.

Therefore, it is possible to have highly resistant peptides that nevertheless:

-

do not bind HLA-DQ2/DQ8 efficiently,

-

are not good substrates for TG2, and/or

-

do not correspond to known T-cell epitopes.

A classic reference on HLA-DQ2 presentation of gluten peptides is available on PNAS. (pnas.org)

4) Concrete example: resistant but non-immunogenic peptide

A very useful example (although engineered) is described by Bethune et al.: the authors created analogs of the 33-mer in which some key glutamines are substituted (e.g., NNN-33-mer and HHH-33-mer). These analogs:

-

remain resistant to simulated digestion (pepsin and also duodenal digestion with pancreatic/brush border proteases),

-

but are not appreciably recognized by TG2, HLA-DQ2, or celiac-specific T cells.

This experimentally demonstrates that resistance to digestion ≠ immunogenicity, even when length and “proline-richness” remain similar. (PMC)

Note: this is a “clean” example because it preserves the resistance feature while breaking (through targeted modifications) the immunological recognition requirements.

5) Summary

Immunogenic gluten sequences tend to be overrepresented among digestion-resistant fragments because resistance allows the persistence of sufficiently long, epitope-rich peptides; however, immunogenicity also requires compatibility with HLA-DQ2/DQ8 presentation and often TG2-mediated modification (deamidation).

Further discussion

So far, the genetic and technological variability of the entire pool of digestion-resistant fragments has not been explored in a systematic and in-depth manner, because most studies focus on known immunogenic peptides rather than on the complete repertoire of proteolysis-resistant fragments in relation to genotype/process. (Frontiers)

Read more

Key evidence-supported points:

1. Peptidomic studies show richness of resistant peptides, but rarely investigate non-immunogenic ones

Analyses based on simulated digestion and mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) reveal hundreds or thousands of peptides after gluten digestion. Only a minority of these coincide with known immunogenic epitopes; most resistant peptides identified in digests are not directly associated with immunogenicity in published studies. (Frontiers)

2. The prevailing interpretation is still “epitope-focused”

Recent literature summarizes the state of the art of methodologies to assess potential immunogenicity (digestion + peptide profiling); however, these reviews also underline that analytical techniques tend to isolate and quantify immunogenic epitopes rather than delineate a complete catalog of persistent, non-immunogenic peptides. (Frontiers)

3. Genotypic variability has been analyzed, but with focus on immunogenic epitopes

Studies on different wheat genotypes show that:

-

digestion and peptide-release profiles vary with genotype,

-

some genotypes show differences in the amount of immunogenic epitopes released,

-

but the pool of resistant non-immunogenic peptides is rarely systematically characterized. (ScienceDirect)

This means that, even though very large peptidomic datasets exist, studies have so far not exploited the “non-immunogenic” component—i.e., digestion-resistant residues lacking immune-presentation motifs—as an object of genotypic and technological comparison aimed at reducing overall biological impact.

4. Research concentrates on clinically relevant immunogenicity

Much of the literature (and analytical strategies) focuses on identification or quantification of so-called Gluten Immunogenic Peptides (GIP), which are fragments detectable in digests and biological matrices that correlate with immune responses in celiac patients and also serve as diagnostic/monitoring markers. (ResearchGate)

This directs attention toward what activates the immune system rather than toward the full profile of non-activating fragments.

Summary

✔ Digestion-resistant but non-immunogenic peptides exist in in vitro digests

✔ There are studies that observe them indirectly (as part of the total peptidome)

❌ There is not yet a systematic body of research that:

-

exhaustively maps resistant non-immunogenic peptides,

-

compares this variability among genotypes,

-

explores how different processes (fermentation, enzymes, baking) quantitatively influence the overall pool of resistant peptides.

In other words: research has the tools (in vitro digestion + LC-MS/MS) to do this, and some preliminary data indicate genotypic variability in digestion profiles, but a comprehensive evaluation of the biological weight of resistant non-immunogenic peptides in relation to genotype/technology has not yet been completed. (ScienceDirect)

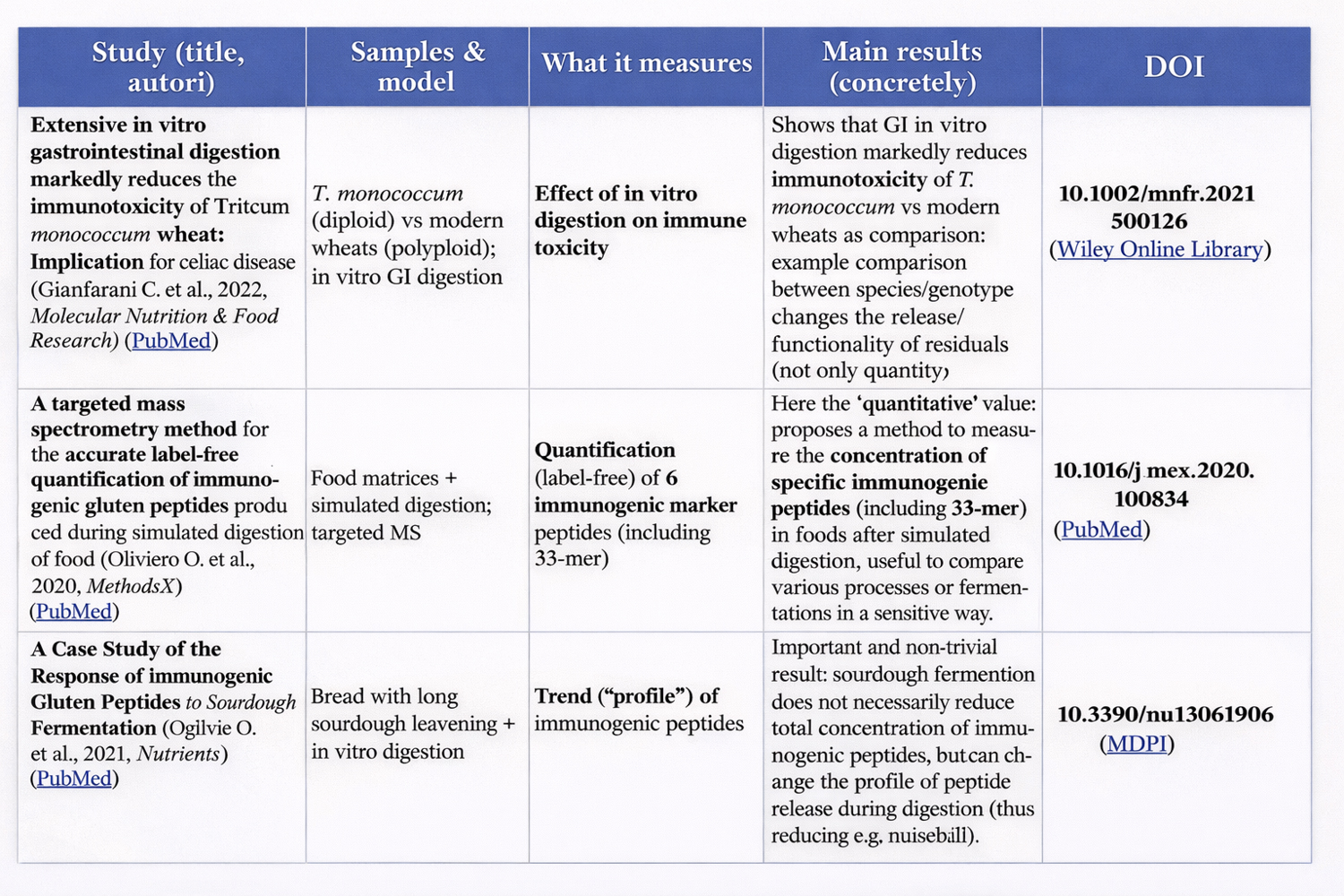

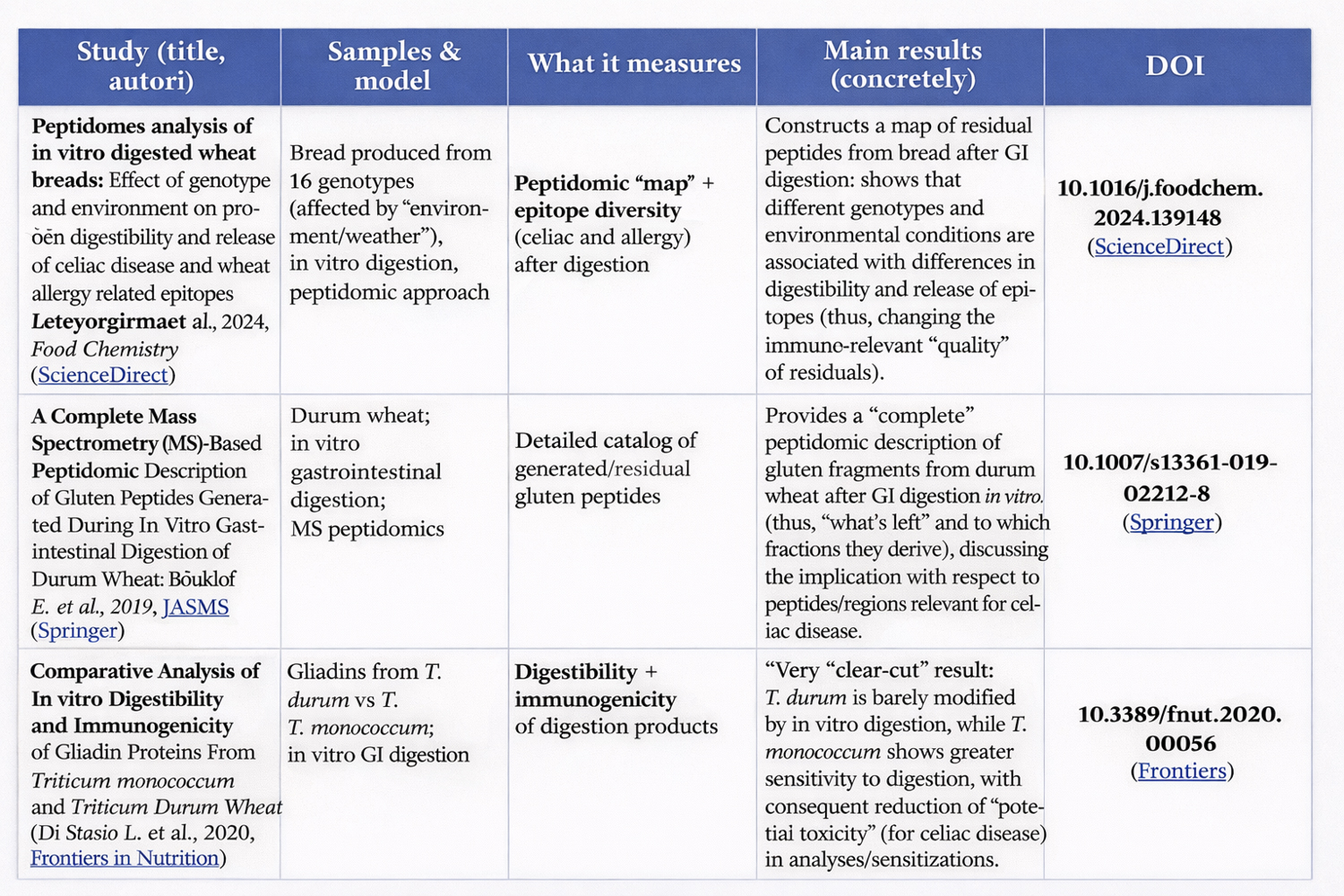

Useful references

Boukid, F. et al. (2019) – A Complete Mass Spectrometry (MS)-Based Peptidomic Description of Gluten Peptides Generated During In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion of Durum Wheat. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. DOI:10.1007/s13361-019-02212-8 — describes the complete peptidome after digestion of durum wheat, highlighting many resistant sequences without focusing only on immunogenic epitopes. (Springer Nature)

Lavoignat, M. et al. (2024) – Peptidomics analysis of in vitro digested wheat breads: Effect of genotype and environment on protein digestibility and release of celiac disease and wheat allergy related epitopes — lays the groundwork for studying genotypic variability in production of resistant peptides and epitopes, but does not yet provide an exhaustive classification of non-immunogenic ones. (ScienceDirect)

Mamone, G. et al. (2023) – Analytical and functional approaches to assess the immunogenicity potential of gluten proteins. Front. Nutr. — methodological review reflecting the current epitope-oriented approach. (Frontiers)

Concise conclusion

Robust peptidomic data show the abundance of proteolysis-resistant fragments in digested gluten; however, the literature has so far prioritized identification and quantification of immunogenic peptides only, leaving largely unexplored the genetic and technological variability in the overall production of resistant non-immunogenic residues and their possible biological role. (Frontiers)