(Insight 3 of Genetic Potential and Process Conditions in Determining Gluten Strength, Digestibility, and Immunogenicity)

The W value does not directly reflect the number or strength of the intrinsic bonds of wheat proteins, but rather represents a functional measure of the resistance of the protein network formed during dough mixing.

This network is the result of the interaction between genetic polymerization potential and the ability of proteins to reorganize and establish new intermolecular bonds under processing conditions.

Does the W value measure the “strength of wheat proteins”?

No.

The W value (Chopin alveograph) measures the energy required to deform and rupture a dough bubble, therefore describing the mechanical resistance of the protein network formed after hydration and mixing. It does not directly measure either the structure of individual proteins or the strength of their internal bonds.

Does the W value represent the strength of bonds present in gliadins and glutenins in the grain?

No.

In the grain, gliadins mainly contain intramolecular disulfide bonds, while glutenins are partially polymerized through intermolecular disulfide bonds. However, these bonds mainly stabilize individual molecules or small aggregates and do not correspond to the network responsible for dough strength.

Functional gluten is built mainly during mixing.

So what does the W value really reflect?

The W value reflects the overall resistance of the protein network formed during mixing, namely:

1 – how much network has been built

2 – how continuous the network is

3 – how capable it is of opposing deformation

In other words, W is a functional measure of the network, not a chemical measure of bonds.

How does wheat genetics influence W?

Genetic makeup influences:

1 – type and quantity of glutenin subunits

2 – number and position of cysteine residues

3 – glutenin/gliadin ratio

These factors determine polymerization potential, i.e., the theoretical ability of proteins to participate in forming intermolecular bonds during mixing. Thus, genotype establishes how large and complex the network can become, not how large it already is in the grain.

Does W depend only on genetic potential?

No.

W depends both on genetic potential and on the ability of proteins to reorganize and create new bonds during mixing.

This ability is influenced by:

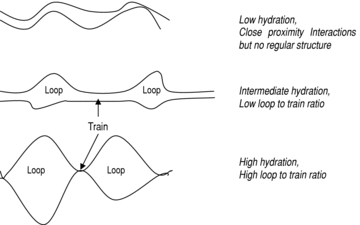

1 – mobility of protein chains

2 – accessibility of reactive groups

3 – rate of thiol–disulfide exchange

4 – hydration, mechanical energy, temperature, and redox conditions

Two wheats with similar genetic potential may therefore develop networks of different strength.

Can a wheat with lower genetic potential develop a higher W?

Yes, within limits.

A wheat with fewer theoretical cross-linking sites but more mobile and reactive proteins may exploit its potential better and form a more efficient network than a wheat with higher theoretical potential but poor utilization of that potential.

Is there a maximum limit to this compensation?

Yes.

A wheat poor in polymerizable glutenins will never reach the W values typical of strong wheats, even under ideal processing conditions. Genetic potential therefore imposes an upper ceiling, while the process determines how close one comes to that ceiling.

Can W be said to measure the “number of bonds”?

No.

W does not measure the number of bonds, but the collective mechanical effect of the network that those bonds help stabilize.

✅ Conclusion

The W value does not reflect either the strength of internal bonds in gliadins and glutenins or the number of bonds present in the grain. It represents a functional measure of the resistance of the protein network that forms during mixing.

This network results from the interaction between:

1 – genetic polymerization potential (what can be built)

2 – capacity for reorganization and new bond formation under processing conditions (what is actually built)

In summary:

✔ What matters most is the network that forms in gluten

✔ But this network is limited by what exists at the origin

In-Depth

What Determines the Genetic Starting Potential of Wheat

The genetic starting potential of a wheat, understood as the intrinsic capacity of its proteins to form an extended and structurally effective gluten network, is mainly determined by the composition and molecular organization of storage proteins. Four factors play a central role.

1 – Type of HMW-GS and LMW-GS Subunits

High-molecular-weight glutenin subunits (HMW-GS) form the main backbone of glutenin polymers. Different allelic variants encode subunits with different length, conformation, and number of cysteine residues.

Some subunits promote longer and more branched chains, while others lead to shorter polymers. Consequently, the type of HMW-GS present directly influences the ability to build a continuous elastic framework.

Low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits (LMW-GS) play a complementary role, acting as connectors and branching points between main chains. The HMW-GS/LMW-GS combination therefore defines the basic polymer architecture.

Impact on potential: determines the load-bearing structure of the network.

2 – Number and Position of Cysteines

Cysteine residues are the chemical sites through which disulfide bonds form.

Not only how many cysteines are present matters, but also where they are located in the protein sequence. Cysteines in exposed regions favor intermolecular bonding, while cysteines in sterically shielded regions tend to form intramolecular bonds.

Impact on potential: defines how many connection points are theoretically available to build the network.

3 – Glutenin/Gliadin Ratio

Glutenins mainly provide elasticity and strength, whereas gliadins mainly contribute viscosity and extensibility. A ratio shifted toward glutenins favors stronger networks; a relative excess of gliadins tends to dilute network continuity.

Impact on potential: determines how much “scaffolding” versus “fluid phase” is available.

4 – Polymer Size Distribution

Even in flour, glutenin polymers exist in a size distribution. Some wheats show a higher proportion of very large polymers (often called glutenin macropolymer, GMP). An initial distribution oriented toward larger polymers favors formation of a continuous network during mixing.

Impact on potential: indicates the level of pre-organization toward extended structures.

Summary

Genetic starting potential does not correspond to the number of bonds already present in the grain, but to the intrinsic capacity of proteins to participate in building an extended network during mixing.

It is mainly determined by:

✔ Type of HMW-GS and LMW-GS subunits

✔ Number and position of cysteines

✔ Glutenin/gliadin ratio

✔ Polymer size distribution

These factors define what is chemically and structurally possible. Processing conditions determine how much of this potential will actually be expressed in the final gluten network.

4

4