Introduction

Gluten is the protein complex that forms when wheat storage proteins—mainly gliadins and glutenins—are hydrated and subjected to mechanical work. During this process, they organize into a continuous three-dimensional network responsible for the viscoelastic properties of dough.

Gluten strength is not an intrinsic and immutable property of individual wheat proteins, but rather an emergent characteristic of the supramolecular organization that develops when storage proteins are hydrated and exposed to mechanical energy during mixing (Shewry & Tatham, 1997; Wieser, 2023). Gluten quality therefore results from the interaction between the initial molecular composition and process-induced structural transformations.

In the grain, gliadins consist mainly of monomeric proteins stabilized by intramolecular disulfide bonds, whereas glutenins are also present as polymers stabilized by intermolecular disulfide bonds, which constitute the structural basis of gluten elasticity (Shewry & Tatham, 1997; Wieser, 2023). Disulfide bridges therefore represent the main covalent cross-links responsible for the formation of a continuous protein network.

It is essential to distinguish between the strength of an individual bond and the ability to form an extended network of bonds. From a chemical perspective, the bond energy of a disulfide bridge is essentially constant; differences among varieties do not arise from “stronger” bonds, but from variations in the number, position, and accessibility of cysteine residues, as well as from the composition of high- and low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits (Wieser, 2023). These features define the genetic cross-linking potential, namely the intrinsic predisposition of proteins to participate in the formation of intermolecular bonds.

The existence and structural importance of disulfide bonds in gluten have been confirmed through direct identification of S–S connections by mass spectrometry, which enabled mapping of specific intra- and intermolecular bonds in gluten proteins (Lutz et al., 2012). This evidence supports the concept that the gluten network is stabilized by a dense web of covalent connections.

During mixing, genetic potential is converted into real structure through dynamic processes of disulfide bond breakage and reformation, mainly via thiol–disulfide exchange reactions (Lagrain et al., 2010). Consequently, the gluten network does not simply correspond to the polymers already present in the grain, but rather represents a reorganized structure that develops as a function of hydration, mechanical energy, temperature, and redox conditions.

Protein composition also influences the architecture of the polymers that form. It has been shown that certain gliadins containing an odd number of cysteine residues can be incorporated into polymeric fractions and act as elements that limit or modulate chain extension (Vensel et al., 2014). This highlights that network quality depends not only on the amount of polymeric proteins, but also on their molecular nature.

In parallel, classic studies have shown that glutenin polymers undergo depolymerization and repolymerization during dough processing, and that the content of glutenin macropolymer (GMP) is closely correlated with dough and gluten strength (Weegels et al., 1996). This dynamic behavior underscores the decisive role of processing conditions in modulating the expression of genetic potential.

Structural Implications for Digestibility

Gluten strength and protein network structure influence not only dough rheology, but also the accessibility of proteins and starch to digestive enzymes. Recent studies show that glutens characterized by a more compact and extensive network are associated with a lower rate of starch digestion and different kinetics of protein degradation, suggesting that the gluten matrix functions as a physical barrier to enzymatic action (Zou et al., 2022).

At the molecular level, gluten proteins are rich in proline and glutamine, a composition that confers intrinsic resistance to major gastrointestinal proteases. As a result, gluten digestion frequently leads to the formation of relatively long and poorly degradable peptides (Di Stasio et al., 2025).

Among these, fragments derived from α-gliadins—such as the well-known 33-mer peptide—exhibit high resistance to proteolysis and contain epitopes recognized by the immune system in individuals with celiac disease (Hernández-Figueroa et al., 2025). The likelihood of formation and persistence of such peptides is influenced by both wheat genotype and gluten structural organization.

Role of Processing in Modulating Peptides

Processing conditions, particularly fermentation, can significantly modify gluten structure and the peptide profile generated during digestion. Sourdough fermentation, through the combined activity of endogenous flour enzymes and microbial proteases, can partially hydrolyze gluten proteins and alter the distribution of released immunogenic peptides (Ogilvie et al., 2021).

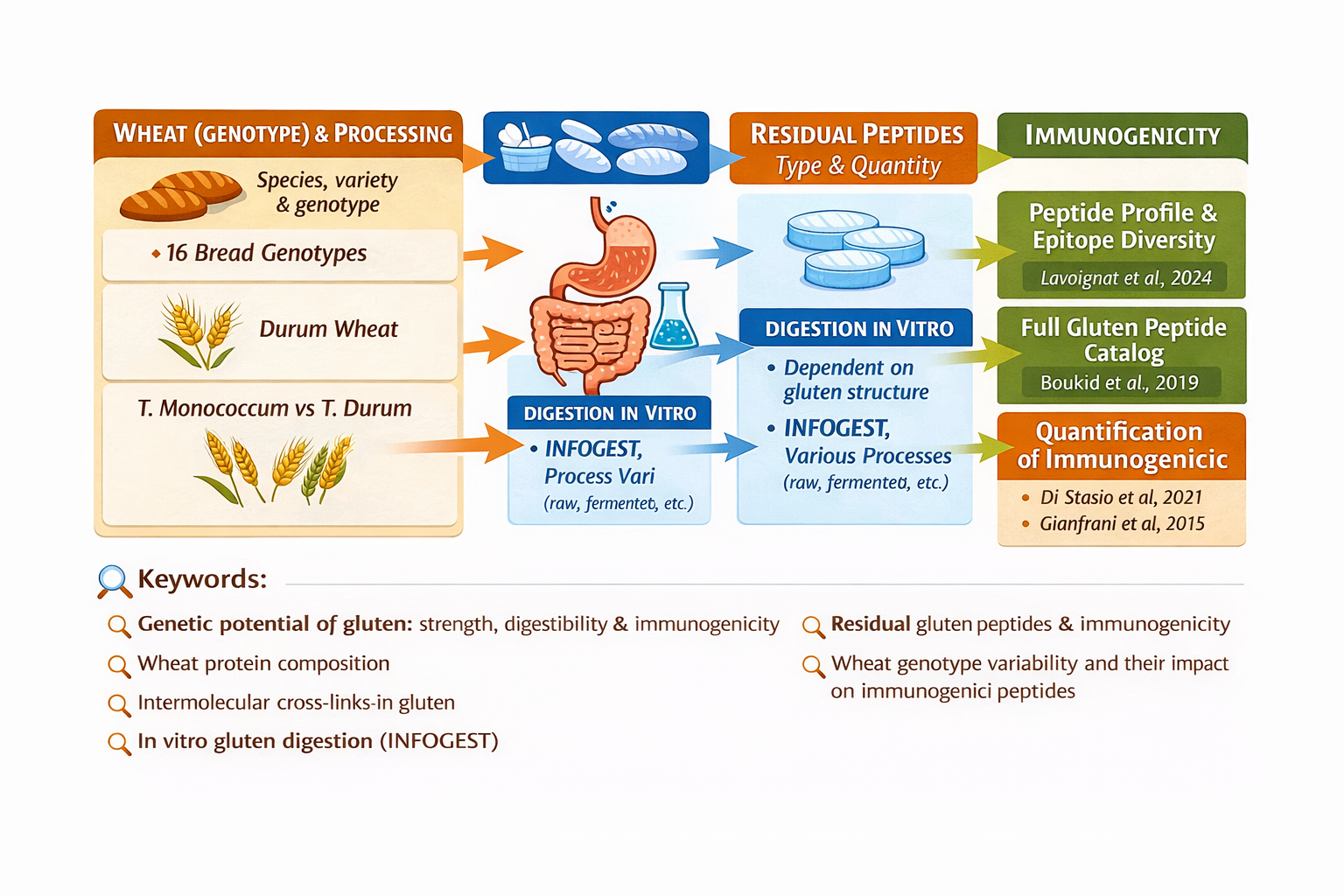

Peptidomic analyses of breads subjected to in vitro digestion reveal considerable peptide diversity, correlated with wheat genotype, agronomic conditions, and processing technologies (Lavoignat et al., 2024). This confirms that the final peptide profile is not determined solely by protein sequence, but also by network architecture and its processing history.

The use of standardized semi-dynamic digestion protocols (such as INFOGEST) allows realistic simulation of oral, gastric, and intestinal phases, enabling quantification of resistant and potentially toxic peptide formation (Freitas et al., 2022). Advanced liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry techniques allow absolute quantification of these fragments and comparative evaluation of varieties and processes.

In parallel, the use of supplemental enzymes or selected microorganisms has been explored as a strategy to enhance degradation of particularly resistant gluten peptides, demonstrating that targeted interventions can significantly reduce the concentration of problematic fragments (Dunaevsky et al., 2021).

Integrated Perspective

Taken together, these findings lead to an integrated view:

The initial molecular composition defines the upper limit of possible gluten connectivity.

Mixing and fermentation determine how much of this potential is actually expressed.

The resulting network structure influences not only technological strength, but also digestibility and the profile of released peptides.

In summary:

✔ What matters most is the network that forms in gluten

✔ But this network is constrained by what exists at the origin

✔ And the resulting network also determines the digestive fate of proteins