✅ RELATED ARTICLE 1

Mitochondria and Oxidative Stress

Highlight

Mitochondria are the main source of ROS in the body and at the same time one of the primary targets of oxidative damage.

Their efficiency largely determines the level of cellular oxidative stress.

What mitochondria do

Produce ATP via oxidative phosphorylation

Regulate apoptosis

Participate in cellular signaling

Regulate nutrient metabolism

During energy production, a small fraction of electrons escapes from the respiratory chain, forming superoxide.

Why mitochondria produce ROS

In the electron transport chain:

O₂ + electron → O₂•⁻

This is a physiological and unavoidable event.

BOX — Physiological production

A moderate production of mitochondrial ROS is necessary for:

adaptive signaling

Nrf2 activation

mitochondrial biogenesis

What is mitochondrial dysfunction

A condition in which:

ATP production decreases

electron leakage increases

ROS production increases

A vicious cycle is created:

Inefficient mitochondrion → more ROS → mitochondrial damage → even less efficient mitochondrion

Factors that damage mitochondria

chronic hyperglycemia

excess oxidized fats

inflammation

toxins

micronutrient deficiencies

sleep deprivation

Mitochondria and chronic diseases

Mitochondrial dysfunction observed in:

type 2 diabetes

cardiovascular disease

neurodegeneration

sarcopenia

aging

How to improve mitochondrial function

Nutrition

adequate protein intake

micronutrients (B vitamins, iron, copper, magnesium)

polyphenols

Physical activity

aerobic exercise

resistance training

Sleep

regularity

7–9 hours

Stress

reduction of chronic load

BOX — Key concept

Oxidative stress is not reduced by “turning off ROS.”

It is reduced by making mitochondria more efficient.

Conclusion

The mitochondrion is the central hub of redox metabolism.

Protecting mitochondrial function means acting upstream on oxidative stress.

✅ RELATED ARTICLE 2

Circadian Rhythm and Oxidative Stress

Highlight

The circadian rhythm coordinates the expression of genes involved in metabolism, energy production, and antioxidant systems.

When this timing system is altered, ROS production increases and the capacity to neutralize them decreases, promoting chronic oxidative stress.

What is the circadian rhythm

A biological timing system of about 24 hours that regulates:

sleep–wake cycle

hormone secretion

energy metabolism

body temperature

cellular repair activity

The main control center is the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, mainly synchronized by light.

Central and peripheral clocks

There are:

one central clock (brain)

peripheral clocks (liver, muscle, pancreas, adipose tissue, heart)

These clocks regulate the temporal expression of thousands of metabolic genes.

BOX — Key concept

Not only what you do, but also when you do it influences redox metabolism.

Link between circadian rhythm and antioxidant systems

Many antioxidant enzymes show circadian oscillations:

superoxide dismutase (SOD)

catalase

glutathione peroxidase

Glutathione synthesis also follows a daily rhythm.

If rhythm is disturbed, these oscillations flatten → lower antioxidant defenses.

Circadian rhythm and mitochondria

The biological clock regulates:

mitochondrial biogenesis

fusion/fission dynamics

respiratory chain efficiency

Circadian misalignment → less efficient mitochondria → greater electron leakage → more ROS.

What disrupts circadian rhythm

evening artificial light

nighttime screen exposure

shift work

insufficient sleep

irregular or nighttime meals

social jet lag

Biological effects of misalignment

Chronic misalignment causes:

increased ROS production

reduced antioxidant activity

increased inflammation

altered glucose and lipid metabolism

BOX — Simplified mechanism

Altered rhythm → inefficient mitochondria → ↑ ROS

Altered rhythm → ↓ antioxidant enzymes

Result: oxidative stress

Circadian rhythm and chronic diseases

Associated with higher risk of:

obesity

type 2 diabetes

metabolic syndrome

cardiovascular disease

cognitive decline

Partly through increased systemic oxidative stress.

Sleep: the main redox “reset”

During sleep:

brain metabolism decreases

antioxidant activity increases

DNA repair systems activate

mitochondrial efficiency improves

Sleep deprivation → measurable increase in oxidative stress markers after only a few nights.

Meal timing and oxidative stress

Eating at biologically inappropriate times:

worsens glycemic control

increases mitochondrial ROS production

promotes lipotoxicity

An eating window aligned with the light–dark cycle improves redox balance.

How to protect circadian rhythm

Light

natural light in the morning

reduced blue light in the evening

Sleep

regular schedule

adequate duration

Meals

consistent timing

avoid large nighttime meals

Physical activity

preferably during daytime

BOX — Key concept

Without a functional circadian rhythm, even a perfect diet and good supplements have limited effectiveness on oxidative stress.

Integration with other pillars

Circadian rhythm acts in synergy with:

mitochondrial function

exercise

stress management

Protecting rhythm is a primary lever in oxidative stress prevention.

Conclusion

The circadian rhythm is a fundamental regulator of redox balance.

Its disruption promotes both increased ROS production and reduced antioxidant defenses, creating conditions for chronic oxidative stress.

Preserving the light–dark rhythm is one of the most powerful and underestimated interventions for cellular health.

✅ RELATED ARTICLE 3

Exercise, Hormesis, and Nrf2: Why Movement Reduces Oxidative Stress

Highlight

Exercise transiently increases ROS production, but this controlled stimulus activates powerful adaptive mechanisms that enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses.

This phenomenon is known as hormesis and is largely mediated by the transcription factor Nrf2.

The exercise paradox

During physical activity:

oxygen consumption increases

mitochondrial electron flux increases

ROS production temporarily increases

Yet, in the long term, regularly trained individuals show lower basal oxidative stress.

BOX — Apparent paradox

Exercise produces ROS, but training reduces chronic oxidative stress.

What is hormesis

Hormesis is a biological principle whereby:

A small stress activates protective adaptations that make the organism more resistant.

In exercise:

ROS transients → signal → adaptation → increased antioxidant capacity

Nrf2: the master regulator

Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2) is a transcription factor that:

senses oxidative stress signals

migrates to the nucleus

activates antioxidant gene expression

Genes regulated by Nrf2 include:

glutathione synthase

glutathione peroxidase

superoxide dismutase

catalase

phase II detoxification enzymes

BOX — Key concept

Nrf2 does not neutralize ROS directly.

It increases the cell’s ability to defend itself.

What happens with regular training

Over time:

glutathione content increases

antioxidant enzymes increase

mitochondrial efficiency improves

basal ROS production decreases

Result: greater redox resilience.

Types of exercise and redox response

Aerobic

brisk walking

moderate running

cycling

Promotes:

mitochondrial biogenesis

Nrf2 activation

Strength

weights

bodyweight training

Promotes:

increased muscle mass

improved glucose metabolism

lower resting ROS production

HIIT

strong adaptive stimulus

useful if properly dosed

When exercise becomes harmful

Excess volume or intensity without recovery:

persistently elevated ROS

reduced immune function

increased inflammation

BOX — Optimal zone

Too little exercise → oxidative stress

Too much exercise → oxidative stress

Moderate dose → protective adaptation

Antioxidants and exercise: caution

High-dose vitamin C and E supplementation:

may blunt Nrf2 activation

may reduce some metabolic benefits of training

Integration with lifestyle

Exercise protection is maximal when combined with:

adequate sleep

balanced nutrition

stress management

Exercise as “medicine”

Physical activity:

reduces cardiovascular risk

improves insulin sensitivity

protects the brain

slows biological aging

Largely through improved redox balance.

BOX — Final key concept

Exercise does not reduce oxidative stress by eliminating ROS,

but by making the organism better able to handle them.

Conclusion

Physical exercise is one of the most powerful physiological tools for controlling oxidative stress.

Through transient ROS increases, it activates Nrf2 and triggers adaptations that strengthen endogenous antioxidant defenses, improving long-term cellular health.

✅ RELATED ARTICLE 4

Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Highlight

Low-grade chronic inflammation is a persistent state of mild immune activation, often asymptomatic, that contributes to the development of many chronic diseases.

It is tightly intertwined with oxidative stress through a mutually amplifying circuit.

What is low-grade chronic inflammation

Unlike acute inflammation (rapid and resolving), it is:

persistent

systemic

low intensity

It does not cause obvious clinical signs but progressively alters tissue physiology.

Difference between acute and chronic inflammation

Acute inflammation

protective response

short duration

promotes healing

Low-grade chronic inflammation

continuous activation

lack of resolution

promotes tissue damage

BOX — Key concept

The problem is not inflammation itself, but its persistence.

Link with oxidative stress

Oxidative stress and inflammation form a bidirectional loop:

ROS activate inflammatory pathways

inflammatory cells produce ROS

BOX — Simplified circuit

ROS → cellular damage → inflammation → ROS production → further damage

Molecular mechanism

ROS activate transcription factors such as:

NF-κB

AP-1

These induce production of:

IL-6

TNF-α

other pro-inflammatory cytokines

Cytokines in turn increase:

oxidase activity

mitochondrial ROS production

Oxidative damage as primary event

Molecular damage caused by ROS can occur:

in absence of immune cells

directly to DNA, lipids, proteins

Inflammation represents a secondary response to damage.

BOX — Crucial point

Oxidative stress can initiate damage.

Inflammation maintains it.

Chronic inflammation and metabolism

Low-grade inflammation:

reduces insulin sensitivity

promotes dysfunctional lipolysis

increases ROS production

Explaining links with:

type 2 diabetes

metabolic syndrome

visceral obesity

Chronic inflammation and target organs

Involved in:

atherosclerosis

fatty liver

neurodegeneration

sarcopenia

Main factors promoting chronic inflammation

caloric excess

ultra-processed diet

sedentary lifestyle

sleep deprivation

psychological stress

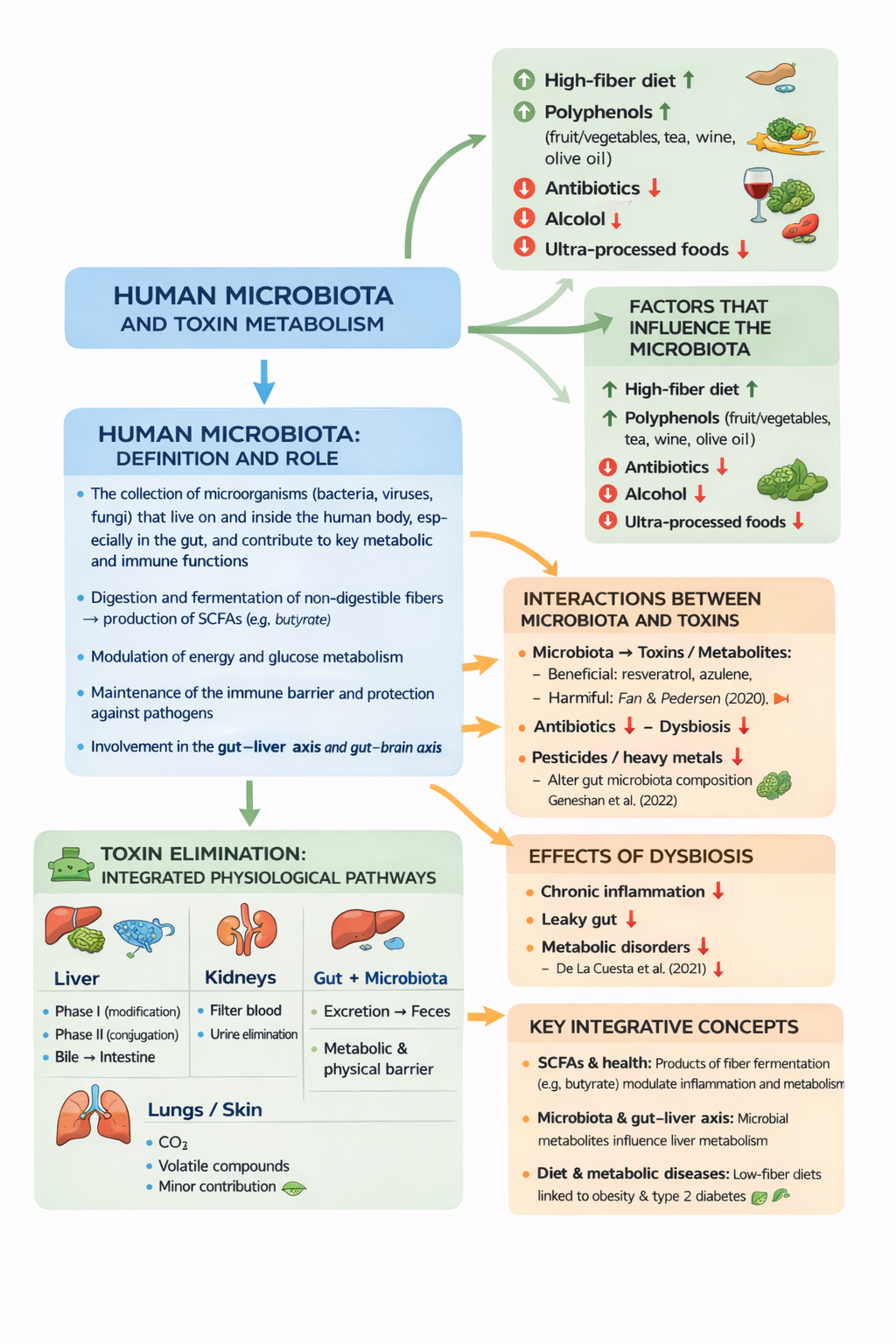

gut dysbiosis

How to reduce chronic inflammation

Diet

high nutrient density

fiber

unsaturated fats

Physical activity

regular

Sleep

7–9 hours

Stress management

relaxation practices

BOX — Key concept

Reducing chronic inflammation also reduces oxidative stress.

Integration with other pillars

Inflammation is modulated by:

mitochondrial function

circadian rhythm

physical exercise

No single intervention is sufficient.

Conclusion

Low-grade chronic inflammation and oxidative stress form an integrated system of biological damage amplification.

Interrupting this circuit requires a systemic approach acting on metabolism, lifestyle, and neuroendocrine regulation.

✅ RELATED ARTICLE 5

Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress: What to Measure and How to Interpret

Highlight

Oxidative stress cannot be evaluated with a single test.

A clinically meaningful assessment requires integration of biomarkers of oxidative damage, inflammation, antioxidant capacity, and metabolic context.

Why there is no “perfect marker”

Oxidative stress is a dynamic process involving:

ROS production

molecular damage

antioxidant response

repair

Each biomarker observes only one part.

BOX — Key concept

A panel is more informative than a single value.

1) Direct biomarkers of oxidative damage

F2-isoprostanes

Derived from non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation

Considered gold standard for lipid oxidative damage

Sample: plasma or urine

Interpretation:

High → high lipid oxidative stress

Malondialdehyde (MDA)

Lipid peroxidation product

More variable than isoprostanes

Interpretation:

Useful as orientative indicator

8-OHdG (8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine)

Marker of oxidative DNA damage

Urine or blood

Interpretation:

High → increased DNA oxidation

2) Antioxidant capacity biomarkers

Reduced glutathione (GSH) and GSH/GSSG ratio

Central redox parameter

Interpretation:

High ratio → good balance

Low ratio → oxidative stress

Total antioxidant capacity (TAC)

Global estimate of ROS-neutralizing ability

Low specificity

Interpretation:

Useful as complement

3) Inflammation-related biomarkers

hs-CRP

Integrated marker of systemic inflammation

Indicative values:

<1 mg/L → low CV risk

1–3 mg/L → intermediate risk

3 mg/L → high risk

IL-6, TNF-α

Pro-inflammatory cytokines

Mainly specialist use

4) Indirect metabolic biomarkers

Glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR

Triglycerides, oxLDL

Ferritin

BOX — Key concept

Metabolic alterations are often the main source of chronic oxidative stress.

5) Advanced mitochondrial biomarkers

Resting lactate

Lactate/pyruvate ratio

CoQ10

Useful in specialist settings.

6) Minimal practical panel

hs-CRP

F2-isoprostanes or MDA

8-OHdG

GSH/GSSG

Glucose + insulin

7) Integrated interpretation example

hs-CRP ↑

MDA ↑

GSH/GSSG ↓

Indicates:

active oxidative stress

associated inflammation

reduced defenses

8) Temporal changes after intervention

Improve first:

GSH/GSSG

hs-CRP

Later:

MDA / F2-isoprostanes

Slowest:

8-OHdG

BOX — Typical sequence

Protection rises → damage falls → DNA improves

9) Common errors

Relying on one marker

Using TAC alone

Interpreting without clinical context

Conclusion

Assessment of oxidative stress requires a multiparametric approach.

Integrating damage, antioxidant capacity, inflammation, and metabolism allows a biologically coherent reading of redox status.

✅ RELATED ARTICLE 6

Antioxidant Supplements: When They Are Truly Needed

Highlight

Antioxidant supplements are not a universal solution to oxidative stress.

In many cases, indiscriminate use is useless or potentially counterproductive.

The most effective strategy remains strengthening endogenous antioxidant defenses.

Why “more antioxidants = less ROS” is wrong

ROS:

are not only toxic byproducts

have essential physiological functions

Indiscriminately eliminating ROS can:

interfere with signaling

reduce beneficial adaptations

BOX — Key concept

The goal is not to suppress ROS, but to restore redox balance.

What dietary antioxidants really do

Dietary antioxidants:

partially buffer ROS

mainly activate signaling pathways (e.g., Nrf2)

Many polyphenols act more as adaptive signals than direct scavengers.

Evidence on high-dose supplements

Chronic high-dose vitamin C and E:

may reduce exercise metabolic benefits

may blunt Nrf2 activation

When supplementation may be useful

Documented deficiencies

vitamin C

vitamin E

selenium

zinc

Increased demand

high stress

infections

toxin exposure

recovery phases

Specific clinical conditions

malabsorption

selected chronic diseases

Types of integrative approach

Direct antioxidants

vitamin C

vitamin E

Glutathione precursors

N-acetylcysteine

glycine

Mitochondrial modulators

CoQ10

alpha-lipoic acid

BOX — Preferred strategy

Better to provide substrates and signals to produce endogenous antioxidants than large doses of external scavengers.

Risks of abuse

reduced training adaptations

possible increased mortality in some populations

false sense of security delaying lifestyle change

Correct intervention sequence

Sleep

Nutrition

Physical activity

Stress management

Only then: targeted supplementation

Supplementation and personalization

Good supplementation:

is temporary

is biomarker-based

is re-evaluated

Conclusion

Antioxidant supplements do not replace a healthy lifestyle.

They may play a targeted role in selected contexts, but the most effective protection against oxidative stress comes from strengthening the body’s intrinsic capacity.