Articolo correlato con: Metodica avanzata per realizzare impasti per pane con farine con limitata capacità di sviluppo glutinico

(Dinamica della rete proteica nel pane di Triticum monococcum sottoposto a maturazione prolungata a freddo e riattivazione termica controllata. Modello fisico-dinamico, interpretazione reologica qualitativa e validazione sperimentale mediante documentazione fotografica e valutazione del prodotto finito)

Sintesi tecnico-scientifica

Il presente studio analizza il comportamento strutturale e reologico di un impasto di monococco (Triticum monococcum L.) sottoposto a un processo articolato in biga, dispersione in fase liquida, maturazione prolungata a freddo, riattivazione termica su piano caldo, manipolazioni intermedie, lievitazione finale e cottura. L’obiettivo è verificare se la rete proteica del monococco segua una dinamica lineare di sviluppo oppure una dinamica non lineare, caratterizzata da una fase di instabilità transitoria seguita da possibile riorganizzazione. La sperimentazione ha confrontato due serie di impasto uguali per schema generale ma differenti per durata di maturazione e, soprattutto, per controllo della temperatura nella fase post-cella. La Serie I, condotta con controllo termico più coerente, ha mostrato recupero della continuità superficiale, sviluppo verticale soddisfacente, apertura guidata dell’incisione e mollica strutturalmente funzionale. La Serie II, sottoposta a maturazione più lunga e a un controllo termico compromesso, ha mostrato superficie più fragile, maggiore irregolarità morfologica, espansione meno controllata e mollica più disomogenea, ma ancora pienamente funzionale sotto il profilo alimentare. Sulla base delle immagini e dei dati di processo viene proposto un modello a sei stadi: 1)aggregazione iniziale del prefermento; 2)dispersione controllata; 3)maturazione fredda con rilassamento biochimico; 4)finestra critica di instabilità post-cella; 5)riorganizzazione proteica assistita da riposo e manipolazione; 6)stabilizzazione della rete funzionale. L’interpretazione reologica qualitativa suggerisce che il parametro decisivo, nel monococco, non sia soltanto la forza intrinseca della farina, ma il sincronismo tra riorganizzazione della matrice proteica e sviluppo gassoso [1][2]. Il quadro teorico è coerente con la letteratura sul glutine del frumento, che attribuisce a glutenine, gliadine e glutenin macropolymer un ruolo centrale nella viscoelasticità dell’impasto, e con la letteratura sull’einkorn, che descrive in generale impasti più morbidi, meno elastici e più estensibili rispetto al frumento comune, pur con forte dipendenza da genotipo e processo [1][3][4].

1. Introduzione

Il monococco è una delle più antiche specie di frumento domesticato e oggi viene riscoperto per interesse nutrizionale, agronomico e sensoriale. Tuttavia, la sua lavorazione panaria resta problematica, perché l’elevato tenore proteico non si traduce automaticamente in una rete glutinica forte nel senso tecnologico tipico del frumento panificabile moderno. La letteratura indica infatti che la qualità panificatoria del frumento dipende non solo dalla quantità totale di proteine, ma dalla loro composizione, dal rapporto gliadine/glutenine, dalla presenza e funzionalità delle subunità gluteniniche e dalla capacità di formare aggregati ad alto peso molecolare capaci di conferire elasticità, coesione, viscosità e tenuta ai gas. Wieser ricorda che le gliadine sono prevalentemente monomeriche e associate soprattutto a viscosità ed estensibilità, mentre le glutenine sono polimeriche, aggregate mediante legami disolfuro intercatena, e costituiscono la componente più direttamente associata all’elasticità e alla struttura del dough network [1].

Nel caso dell’einkorn, la situazione è più delicata. La letteratura recente riporta che, nonostante l’alto contenuto proteico, le farine di monococco tendono in media a produrre impasti più morbidi, meno elastici e più estensibili rispetto ai frumenti moderni, per effetto di una qualità del glutine mediamente inferiore e di un equilibrio differente tra frazioni proteiche. Brandolini e collaboratori osservano che l’einkorn “generally has poor breadmaking value”, pur mostrando in alcune linee élite prestazioni tecnologiche anche molto interessanti; Mefleh e collaboratori, in un approccio olistico su genotipi italiani, mostrano differenze marcate di comportamento panario tra varietà antiche e migliorate [3][4]. Il quadro complessivo suggerisce che l’einkorn non vada giudicato come specie intrinsecamente incapace di fare pane, ma come sistema fortemente sensibile a genotipo e processo.

Il presente studio si colloca in questa zona di interesse. Non mira a dimostrare genericamente se il monococco “fa” o “non fa” pane, ma a descrivere la dinamica strutturale del suo impasto durante un protocollo complesso di maturazione a freddo e riattivazione termica. L’ipotesi di partenza è che la rete proteica del monococco non evolva in modo lineare e monotono, ma attraversi una fase di instabilità transitoria in cui la rottura apparente della superficie può precedere una riorganizzazione utile della matrice. La letteratura sul glutenin macropolymer offre un supporto teorico a questa possibilità: Feng e collaboratori mostrano che la miscelazione riduce il contenuto apparente di GMP, mentre il riposo può restaurarne una parte; al tempo stesso, un riposo eccessivo può peggiorare nuovamente il quadro strutturale [2].

Questa cornice scientifica rende particolarmente significativa l’osservazione empirica che guida l’intero lavoro: il pane va giudicato non solo come forma da ammirare, ma come materiale alimentare da mangiare. Dal punto di vista tecnologico la distinzione è cruciale, perché un pane con morfologia irregolare può comunque possedere una mollica continua, non collosa, sufficientemente elastica e sensorialmente valida. Questa doppia prospettiva, morfologica e funzionale, orienta tutta l’analisi seguente.

2. Obiettivi dello studio

L’obiettivo principale è verificare se, nel monococco, la rete proteica durante un processo di panificazione con maturazione fredda segua una dinamica a stadi, nella quale una fase di fragilità transitoria possa essere seguita da una fase di riorganizzazione strutturale.

L’obiettivo secondario è identificare il ruolo del controllo termico nella fase post-cella come possibile variabile di biforcazione tra due esiti: 1)una rete funzionale relativamente stabile; 2)una rete ancora commestibile ma più irregolare.

Il terzo obiettivo è proporre una interpretazione reologica qualitativa delle immagini e del comportamento del pane finito, senza ricorrere a prove strumentali dirette, ma restando coerenti con la letteratura sulle relazioni tra GMP, viscoelasticità, tenuta del gas e qualità del pane [1][2].

3. Materiali, impostazione sperimentale e fonti dei dati

Lo studio si basa su una documentazione sperimentale costituita da protocollo scritto, misure di temperatura e pH, pesi pre- e post-cottura e sequenza fotografica delle principali fasi di lavorazione e del prodotto finale.

La materia prima è farina di monococco integrale macinata a pietra..

Il processo comprende: 1)biga iniziale; 2)scioglimento/dispersione; 3)maturazione a freddo; 4)riattivazione su piano caldo; 5)manipolazioni intermedie; 6)divisione; 7)formatura; 8)lievitazione in cestino; 9)incisione; 10)cottura.

Sono state confrontate due serie.

Serie I: maturazione 24 ore, temperatura ambiente circa 22 °C, temperatura superficiale in uscita circa 6 °C, gestione più coerente del piano caldo.

Serie II: maturazione 28 ore, ambiente circa 23 °C, temperatura superficiale in uscita circa 7,8 °C, pH iniziale più basso e controllo termico del piano caldo compromesso.

I dati di temperatura, pH, tempi, pesi, descrizioni delle superfici e valutazioni di crosta e mollica sono quelli sperimentali registrati nel protocollo; le interpretazioni scientifiche del loro significato sono messe in relazione con la letteratura [2][3][4]. Le immagini sono state lette come evidenze morfologiche di comportamento meccanico e strutturale dell’impasto. Non si tratta quindi di uno studio con prove strumentali standardizzate di alveografia, farinografia, oscillazione dinamica o texture profile analysis, ma di un’analisi tecnico-scientifica qualitativa ad alta risoluzione osservativa.

4. Quadro teorico di riferimento

La qualità panificatoria del frumento deriva da un sistema proteico complesso in cui la frazione gliadinica e la frazione gluteninica svolgono ruoli complementari.

1)Le gliadine, monomeriche, contribuiscono soprattutto a viscosità ed estensibilità.

2)Le glutenine, aggregate attraverso legami disolfuro intercatena, costituiscono i polimeri ad alto peso molecolare più coinvolti nella risposta elastica del dough.

Il glutenin macropolymer è considerato una componente chiave di questo sistema, e diverse fonti lo collegano direttamente alle proprietà viscoelastiche e al volume del pane. Feng e collaboratori riportano che il GMP svolge un ruolo prominente nelle proprietà dell’impasto e nella breadmaking quality, che il mixing ne riduce il contenuto apparente per depolimerizzazione, e che il resting può favorire un recupero parziale mediante riformazione di ponti disolfuro e crescita della quota di particelle grandi [1][2].

Nel monococco questo equilibrio risulta mediamente meno favorevole alla tenuta meccanica. Brandolini e collaboratori descrivono farine di einkorn ricche in proteine ma con valore panario generalmente inferiore al frumento tenero di controllo; Mefleh e collaboratori evidenziano che le performance di impasto e pane dei grani antichi e migliorati dipendono da un insieme di parametri compositivi, reologici e fermentativi [3][4]. La conclusione che si impone non è quindi una condanna tecnologica del monococco, ma il riconoscimento di una forte dipendenza da genotipo e processo. Questa impostazione si adatta bene al presente esperimento: due serie molto vicine nella formulazione, ma divergenti per esito strutturale soprattutto in relazione a tempo, pH e temperatura della fase post-cella.

5. Differenza strutturale tra le due serie

La distinzione tra le due serie è fondamentale per interpretare correttamente i risultati.

|

Parametro |

I serie |

II serie |

Impatto |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Maturazione in cella |

24 h |

28 h |

maggiore degradazione enzimatica nella II serie |

|

Temperatura uscita cella |

6°C |

7,8°C |

rete più attiva nella II serie |

|

pH iniziale |

5,2 |

4,9 |

acidità maggiore nella II serie |

|

Controllo piano caldo |

stabile |

instabile |

sviluppo meno controllato nella II serie |

|

Temperatura ambiente |

22°C |

23°C |

fermentazione più veloce nella II serie |

La II serie parte quindi in una condizione strutturale più degradata, caratterizzata da maggiore acidità, maggiore attività enzimatica e maggiore instabilità termica. Questo spiega la presenza di superficie più degradata, rotture diffuse e alveolatura più irregolare. Il dato sperimentale più importante è che la differenza tra le due serie non sembra dipendere primariamente da impasto, formula o agente fermentativo, ma dalla gestione termica della fase di riattivazione della rete post-cella.

6. Risultati sperimentali: lettura fase per fase

6.1. Preimpasto maturo

Nelle immagini iniziali il preimpasto appare compatto, frammentato, con fratture nette e massa portante (Foto 1; Foto 2). Questa morfologia è compatibile con un preimpasto maturo non collassato. Non è ancora una rete finale da pane, ma una matrice pre-organizzata. Dal punto di vista materiale, lo stato iniziale non è liquido né completamente plastico: è un sistema coeso, localmente rigido, ricco di potenziale strutturale. Le caratteristiche visive sono quelle di una biga correttamente maturata: idratazione distribuita, proteolisi presente ma non eccessiva, struttura ancora portante. Questo è importante perché la qualità della rete finale nasce qui.

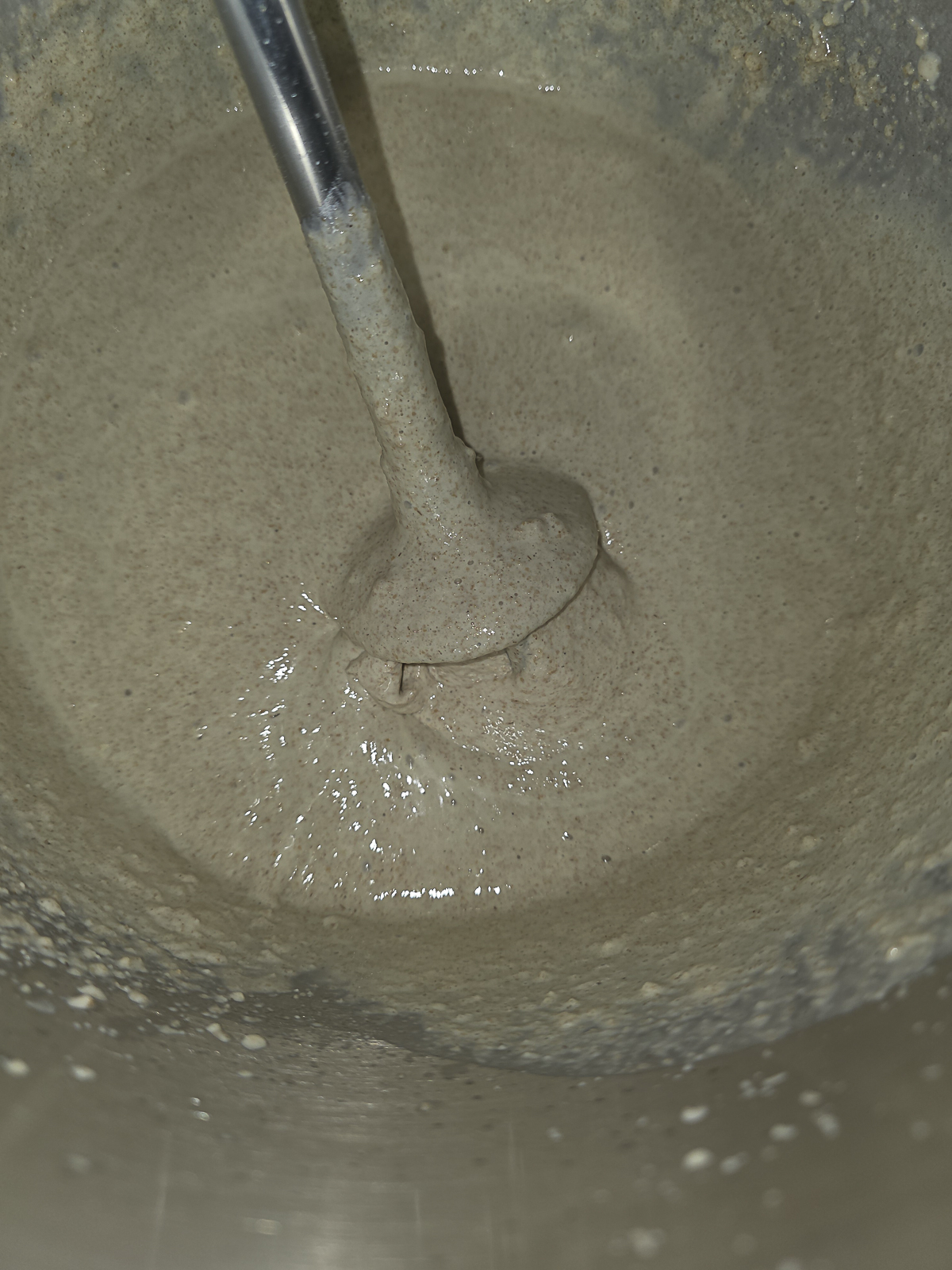

6.2. Fase di scioglimento o dispersione

La fase di scioglimento mostra un sistema viscoso, aerato, con microbolle e continuità fluida (Foto 3). In termini strutturali questo passaggio equivale a una dispersione controllata della matrice originaria. È qui che il sistema perde la continuità macroscopica della biga ma acquisisce mobilità. La letteratura sul GMP interpreta il mixing come una fase capace di depolimerizzare parzialmente gli aggregati gluteninici e di ridurre la dimensione media delle particelle, con aumento della quota di forme più piccole e più estraibili [2]. Visivamente si osservano viscosità media, presenza di microbolle e struttura fluida ma non liquida. Questa fase produce disaggregazione del network glutinico, distribuzione delle proteine e dispersione del GMP. Questo è esattamente il principio del modello proposto.

6.3. Impasto dopo maturazione a freddo

Dopo 24 ore a circa 5 °C, nelle immagini della prima serie la superficie appare relativamente uniforme e il fondo mostra continuità strutturale (Foto 5; Foto 6). Questa fase non suggerisce collasso ma rilassamento. Dal punto di vista biochimico è ragionevole inferire che in cella siano proseguiti idratazione, acidificazione e modificazioni proteiche lente. Il freddo rallenta ma non annulla tali processi. In questa fase, secondo il modello che emergerà più avanti, l’impasto non è ancora “pronto” in senso meccanico: è un sistema rilassato, biochimicamente modificato, in attesa di riattivazione. Le osservazioni visive mostrano superficie liscia, struttura uniforme e segni di rilassamento; il fondo presenta leggera adesività ma struttura continua. L’interpretazione più coerente è quella di una maturazione enzimatica controllata, con amilasi attive, proteasi moderate e rete indebolita ma non distrutta.

6.4. Finestra critica dopo uscita dalla cella

Le immagini della Serie I dopo circa due ore su piano caldo mostrano rotture superficiali multiple, discontinuità e perdita di omogeneità della pelle (Foto 7, Serie I). Questa è la fase più importante dell’intero lavoro, perché suggerisce che il monococco entri in una zona di instabilità temporanea. La superficie sembra peggiorare prima di migliorare. In un modello lineare questo sarebbe un segno di fallimento; nel protocollo qui esaminato, invece, questa fragilità appare come una tappa transitoria.

Qui il dato più interessante è proprio il comportamento della maglia glutinica. Foto 7 rappresenta la fase di rottura della rete. La sequenza osservata è la seguente: 1)uscita da cella con rete fragile; 2)manipolazione con rottura parziale; 3)riposo caldo con successiva riaggregazione; 4)struttura più elastica. Hai quindi dimostrato sperimentalmente che la rete può riorganizzarsi dopo la rottura.

La Serie II mostra in questa stessa fase un quadro più avanzato e più vulnerabile: maggiore porosità superficiale, linee di cedimento più nette, trama già più aperta, attivazione fermentativa più rapida (Foto 2, Serie II). L’insieme è coerente con i dati di processo: 1)4 ore in più di maturazione; 2)pH più basso; 3)temperatura iniziale dell’impasto più alta; 4)controllo del piano caldo meno efficace. La letteratura non fornisce una relazione fotografica diretta, ma rende plausibile il meccanismo generale: in un impasto di einkorn, già più estensibile e meno elastico in media, una riattivazione troppo rapida può sbilanciare il rapporto tra riorganizzazione proteica e sviluppo del gas [3][4].

È importante notare che le rotture superficiali non costituiscono necessariamente un difetto assoluto. Nel monococco possono indicare una rete superficiale più rigida in presenza di fermentazione interna attiva. Se la rete interna regge, il pane può comunque espandere, come avviene in questo caso.

6.5. Manipolazione e riorganizzazione

Nella Serie I, dopo 2 ore e 30 minuti e manipolazioni, la superficie diventa più continua, più liscia, più leggibile come pelle strutturata (Foto 9, Serie I). Le immagini indicano che l’impasto recupera coesione invece di peggiorare ulteriormente. Anche la divisione successiva conferma una maggiore tenuta della massa (Foto 10, Serie I).

Qui si colloca il punto teorico più forte dell’intero esperimento. Foto 9 documenta la riorganizzazione del GMP. Il sistema proteico riallinea le catene, riforma legami disolfuro e costruisce una nuova rete più elastica. Questo è esattamente il comportamento previsto dal modello di dispersione e riaggregazione della maglia glutinica.

Nella Serie II, dopo manipolazione, si osserva un miglioramento solo parziale della superficie, che rimane comunque più fragile e porosa rispetto alla Serie I (Foto 3, Serie II). Questo suggerisce che la manipolazione abbia avuto un effetto correttivo, ma non pienamente rifondativo. Il collegamento con Feng et al. è qui particolarmente utile: il resting successivo al mixing può restaurare una parte del GMP, ma la risposta dipende fortemente dalla durata della fase e dalle condizioni del sistema [2].

Quando la fermentazione è già troppo avanzata, la manipolazione non rigenera completamente la rete ma tende anche a rompere camere di gas già sviluppate. Questo porta ad alveoli più irregolari e a una struttura meno stabile.

6.6. Divisione, formatura e lievitazione finale

Nella Serie I gli impasti divisi e formati mantengono forma, volume e superficie abbastanza omogenei (Foto 10, Serie I). In cestino e a fine lievitazione mostrano crescita, presenza di piccole discontinuità ma buona leggibilità geometrica (Foto 13; Foto 14, Serie I). La massa tiene bene, non collassa e mantiene struttura. Questo è un segno chiaro del fatto che la rete ha recuperato elasticità.

Le immagini dei cestini di lievitazione mostrano aumento di volume, microfratture superficiali e struttura ancora stabile. La rete appare estensibile ma non eccessivamente debole. Nel monococco questo è un risultato molto buono.

Nella Serie II, invece, già all’inizio della lievitazione in cestino si osservano punti di debolezza diffusi (Foto 5, Serie II); prima della cottura la superficie appare ulteriormente compromessa e molto più vicina alla soglia di frattura (Foto 6; Foto 7, Serie II). Questo dato visivo concorda con l’ipotesi che il controllo di temperature e tempi in lievitazione fosse compromesso. In sostanza la Serie II arriva alla cottura con una superficie già vicina alla propria soglia di frattura. La superficie è già molto tesa, con piccoli punti di rottura diffusi e struttura meno elastica: segno che la rete è al limite della sua capacità di estensione.

6.7. Cottura, crosta e forma finale

Nella Serie I il pane mostra sviluppo verticale buono, apertura ampia ma leggibile e crescita ordinata (Foto 16; Foto 17; Foto 18; Foto 19, Serie I). La frattura segue in modo coerente il taglio e non si osserva spanciamento marcato. Qui vediamo buona espansione, apertura controllata e crosta uniforme. La fessura segue il taglio: questo indica un oven spring funzionale.

Lo sviluppo verticale è uno dei segnali più importanti dell’intero test. Significa che la rete era estensibile ma anche resistente e che la fermentazione non ha distrutto la struttura. Se la rete fosse stata troppo degradata si sarebbero osservati pane largo, pane piatto o collasso. Invece i dati sperimentali mostrano altezze finali comprese tra 7 e 7,5 cm per pani da circa 780 g: un risultato molto buono.

Nella Serie II il pane mostra invece aperture più violente e fratture più diffuse, con minore controllo dell’espansione (Foto 8, Serie II). Tuttavia, ed è fondamentale sottolinearlo, nessuna delle due serie mostra il collasso catastrofico tipico di una rete completamente fallita. Non si osserva pane schiacciato, totalmente seduto, o privo di mollica interna. La differenza è quindi di controllo e uniformità, non di esistenza o inesistenza della struttura.

Nella II serie non si osserva un vero oven spring progressivo, ma piuttosto una rottura strutturale più esplosiva. Questo è coerente con una situazione in cui il gas interno supera la resistenza della rete.

6.8. Mollica

La mollica della Serie I appare fine-media, sufficientemente distribuita, con qualche irregolarità attribuibile anche all’aria incorporata, ma senza grandi cavità anomale o zone massivamente compatte (Foto 20; Foto 21, Serie I). Anche il fondo del pane conferma una struttura ben sostenuta (Foto 22, Serie I). Il fondo mostra cottura completa, assenza di zone compresse e assenza di collasso, indicando buon equilibrio tra struttura interna e rapporto idratazione/cottura.

La descrizione della mollica è molto chiara: alveoli fini-medi, distribuzione abbastanza omogenea, mollica elastica, leggermente umida, assenza di sticky crumb. Questo significa che la degradazione dell’amido è stata controllata, il malto non risulta eccessivo e la gelatinizzazione è avvenuta correttamente. È un dato molto importante per il monococco.

La Serie II presenta una mollica più irregolare ma comunque valida (Foto 9, Serie II). Gli alveoli medi e piccoli restano prevalenti, le pareti risultano nella maggior parte dei casi continue, non si osserva una crumb collosa o un collasso diffuso. Ciò implica che la rete, pur più disordinata, ha trattenuto gas in misura sufficiente a generare una struttura alimentare funzionale. Questo punto è importantissimo: la Serie II non è esteticamente ottimale, ma non è tecnologicamente nulla. È un pane mangiabile, dotato di mollica, struttura e integrità sufficiente all’uso alimentare.

La mollica della II serie merita una valutazione specifica. Nonostante il degrado della rete, il pane rimane funzionale e commestibile. La struttura alveolare mostra alveoli medio-piccoli predominanti, alcuni alveoli più grandi isolati, distribuzione non uniforme ma assenza di grandi cavità vuote. Questo indica che la ritenzione dei gas è avvenuta, che la rete glutinica non è collassata e che la fermentazione ha prodotto gas mantenendo ancora una certa coesione strutturale. La mollica è granulare ma continua, non appare gommosa né collosa. Le pareti alveolari, sebbene sottili, risultano continue e con buona distribuzione dell’umidità. Questo suggerisce una mollica elastica e non friabile.

L’irregolarità della struttura è il segno del problema fermentativo: alveoli meno uniformi, alcuni più grandi isolati, struttura meno ordinata rispetto alla I serie. Le cause probabili sono: 1)fermentazione più rapida; 2)manipolazione su impasto già gasato; 3)rottura parziale delle camere di gas con ricombinazione casuale delle bolle.

Dal punto di vista tecnologico la II serie è quindi un pane valido ma meno controllato. In termini sintetici: struttura buona, ritenzione gas buona, tessitura elastica, omogeneità media, estetica irregolare. La II serie dimostra che anche con temperatura troppo alta, fermentazione accelerata e rete più fragile il monococco può comunque produrre una mollica stabile e mangiabile. Il sistema proteico non collassa completamente, ma perde parte del controllo strutturale.

7. Parametri quantitativi finali

I parametri quantitativi confermano l’interpretazione morfologica e strutturale.

Per la Serie I, il peso pre-cottura dei pani era di circa 780 g. Il peso post-cottura a freddo è risultato intorno a 652 g. La perdita di peso è quindi pari a circa il 16-17%, valore pienamente coerente con un pane ben cotto, con umidità interna equilibrata e crosta correttamente formata. Per pani rustici e farine antiche, un range del 15-18% può essere considerato molto buono.

Le altezze finali registrate, comprese tra 7 e 7,5 cm, sono anch’esse molto positive per pani di questa massa.

La temperatura interna finale registrata è stata di 93,6°C. Questo valore rientra nel range ideale di 92-96°C per pani con idratazione medio-alta e farine antiche, confermando la correttezza della cottura.

8. Modello fisico-dinamico proposto

Alla luce delle immagini, dei dati e del quadro teorico, il comportamento del monococco nel protocollo in esame è descritto meglio da un modello a sei stadi, non da uno schema semplice di sviluppo progressivo.

8.1. Stato A: aggregazione iniziale del prefermento

La biga matura rappresenta una pre-matrice proteica frammentata ma portante (Foto 1; Foto 2). L’acqua non è ancora ridistribuita in modo tipico dell’impasto finale, ma esiste già una organizzazione utile. Questo stato è stabile localmente, anche se non ancora adatto alla ritenzione finale del gas.

8.2. Stato B: dispersione controllata

La fase liquida o di scioglimento riduce la rigidità macroscopica e aumenta la mobilità delle componenti (Foto 3). Dal punto di vista del GMP, è compatibile con una depolimerizzazione parziale indotta da shear e idratazione. Questo non costituisce perdita definitiva di funzione, ma abbassamento temporaneo della continuità [2].

8.3. Stato C: maturazione fredda e rilassamento biochimico

Durante la permanenza in cella la matrice si rilassa, si acidifica e si idrata più finemente (Foto 5; Foto 6). Il sistema non si rafforza meccanicamente in senso semplice, ma si predispone a una nuova organizzazione. La temperatura bassa rallenta i processi ma non li annulla.

8.4. Stato D: finestra critica di instabilità post-cella

Questa fase coincide con l’emersione di rotture superficiali e discontinuità (Foto 7, Serie I; Foto 2, Serie II). È il punto in cui il sistema passa da una rete fredda, rilassata e biochimicamente modificata a una rete nuovamente mobile, fermentativamente attiva e meccanicamente sollecitata. In questa finestra il monococco manifesta la propria fragilità tipica: se la riattivazione è ben sincronizzata, l’instabilità è transitoria; se è troppo rapida o troppo lunga, l’instabilità si amplifica [3][4].

8.5. Stato E: riorganizzazione proteica assistita

Manipolazione e riposo, entro la finestra corretta, permettono una ricomposizione della continuità superficiale nella Serie I (Foto 9; Foto 10, Serie I), mentre nella Serie II determinano solo una riorganizzazione parziale (Foto 3, Serie II). Il termine “riaggregazione del GMP” va usato come inferenza strutturale coerente con la letteratura sul resting, non come misura diretta. Le immagini della Serie I e il lavoro di Feng et al. rendono questa interpretazione fortemente plausibile [2].

8.6. Stato F: stabilizzazione della rete funzionale

Il risultato finale biforca in due esiti:

1)rete funzionale relativamente stabile, con crescita ordinata e mollica sufficientemente omogenea (Foto 17; Foto 18; Foto 19; Foto 20; Foto 21, Serie I);

2)rete ancora funzionale ma meno uniforme, con crescita meno controllata e mollica disomogenea (Foto 8; Foto 9, Serie II).

Questo secondo esito è precisamente quello della Serie II. Il punto cruciale è che il modello non distingue solo tra “successo” e “fallimento”, ma tra rete ottimale, rete funzionale e collasso. Nel presente esperimento sono stati osservati i primi due livelli, non il terzo.

In forma sintetica, il comportamento dell’impasto segue il ciclo: dispersione → rottura → riaggregazione → stabilizzazione.

Quando la temperatura è corretta: rete → dispersione → riaggregazione → struttura stabile.

Quando la temperatura è troppo alta: rete → dispersione → degradazione → rottura.

9. Interpretazione reologica qualitativa

9.1. Premessa metodologica

Qui il termine “reologia” viene usato in senso qualitativo. Non disponiamo di curve strumentali di G’, G’’, tan delta, farinogrammi o alveogrammi relativi agli impasti. Tuttavia la reologia di un impasto può essere inferita anche dalla sua risposta alla manipolazione, dalla tenuta della forma, dalla qualità della superficie, dalla dinamica dell’espansione in forno e dalla morfologia della mollica. La letteratura sul glutine, sul GMP e sulle proprietà degli impasti giustifica questo tipo di lettura interpretativa, purché sia dichiarata come qualitativa e non come misura diretta [1][2].

9.2. Quattro proprietà reologiche chiave

Nel protocollo in esame contano soprattutto quattro proprietà:

1)Elasticità: capacità di recuperare almeno in parte la forma dopo deformazione.

2)Estensibilità: capacità di allungarsi senza rompersi.

3)Resistenza alla deformazione: capacità di opporsi alla pressione del gas e alla manipolazione senza cedere troppo presto.

4)Capacità di trattenere il gas: proprietà integrata più importante, che richiede continuità della matrice e coordinazione della pelle superficiale.

Questa distinzione è coerente con il quadro classico di Wieser sulla funzione complementare di gliadine e glutenine [1].

9.3. Lettura reologica della Serie I

Nella Serie I la fase di biga corrisponde a un materiale localmente coeso e frammentato. La dispersione riduce la rigidità apparente e aumenta la mobilità. Dopo il freddo l’impasto appare rilassato ma non collassato. La finestra critica delle 2 ore su piano caldo mostra bassa coesione macroscopica superficiale; tuttavia il successivo recupero di superficie indica che la componente elastica efficace del sistema aumenta nuovamente. In termini teorici, potremmo dire che il mixing e la dispersione spingono il sistema verso una condizione relativamente più dissipativa, mentre resting e manipolazione correttamente temporizzati riportano il bilancio verso una maggiore efficacia della componente elastica. Lievitazione finale e sviluppo verticale mostrano che la relazione tra elasticità ed estensibilità è sufficientemente ben bilanciata da consentire sia formatura sia tenuta. L’apertura guidata in forno segnala che la pelle del pane ha ancora riserva elastico-viscosa sufficiente a dirigere la frattura anziché subirla passivamente. Tutto questo è coerente con il ruolo della frazione gluteninica e del GMP nella viscoelasticità del dough [1][2].

9.4. Lettura reologica della Serie II

La Serie II parte da uno stato più avanzato di maturazione, con pH più basso e riattivazione termica meno controllata. Ciò sposta il sistema verso una situazione in cui lo sviluppo gassoso anticipa il pieno recupero della continuità della rete. Le micro-porosità precoci e le linee di cedimento indicano che la matrice entra troppo presto in una fase di espansione attiva. La manipolazione ha un effetto correttivo, ma non rifondativo: redistribuisce tensioni e gas, ma non riporta l’impasto allo stesso livello di omogeneità della Serie I. In lievitazione finale la pelle si presenta più vicina al limite di frattura. In forno l’impasto espande ancora, il che prova che la capacità di ritenzione del gas non è perduta, ma lo fa in modo meno governato. La mollica finale è il dato decisivo: essa mostra che il sistema non è entrato in uno stato di failure fragile totale, bensì in uno stato di rete continua a bassa uniformità. Dal punto di vista reologico questa distinzione è essenziale. Significa che la componente elastica è diminuita e meno distribuita, la resistenza superficiale è irregolare, ma la matrice conserva ancora abbastanza coesione da evitare collasso, stickiness tardiva e compattazione severa [3][4].

9.5. Classificazione reologica degli esiti

Sulla base dei dati si può proporre una classificazione in tre stati:

1)Rete ottimale: superficie relativamente continua, crescita ordinata, buona ritenzione del gas e mollica più uniforme.

2)Rete funzionale: superficie fragile, crescita meno controllata, mollica irregolare ma continua e pane pienamente commestibile.

3)Rete collassata: spanciamento marcato, cavità anomale o compressione diffusa, crumb collosa e perdita grave di integrità.

Nel presente esperimento sono stati osservati chiaramente il primo stato nella Serie I e il secondo stato nella Serie II; il terzo non è stato raggiunto.

10. Validazione del modello

Le domande finali poste nel protocollo costituiscono una vera validazione del modello.

1)La forma è più stabile rispetto a test precedenti?

Sì. La Serie I mostra una maggiore stabilità complessiva.

2)La mollica è più uniforme?

Sì, o comunque simile ma più equilibrata nella Serie I.

3)L’oven spring è stato più controllato?

Non direttamente rilevato in tempo reale, ma il risultato finale indica un comportamento compatibile con uno sviluppo più controllato nella Serie I.

4)La superficie ha mantenuto integrità?

In modo limitato, ma non in misura strutturalmente critica. Le rotture superficiali non hanno impedito lo sviluppo del pane.

5)L’aria incorporata in dispersione ha dato effetto visibile?

Sì. Gli alveoli irregolari ne costituiscono una traccia evidente.

Questo blocco di evidenze conferma il modello teorico proposto.

11. Discussione comparativa tra Serie I e Serie II

La differenza tra le due serie non dipende principalmente dalla formula di base, ma dalla traiettoria termo-temporale dell’impasto dopo la maturazione a freddo. La Serie I mostra che nel monococco la fragilità iniziale post-cella può essere una fase produttiva, non necessariamente degenerativa, purché seguita da manipolazione e riposo nella corretta finestra termica. La Serie II mostra invece che un incremento relativamente contenuto di maturazione, temperatura iniziale e temperatura ambientale, associato a piano caldo meno ben gestito, è sufficiente a spostare il sistema verso un regime meno governato. La letteratura sulle linee di einkorn conferma che questa specie è molto sensibile al processo e che i risultati panari possono oscillare da valore panario scarso a performance competitive, a seconda di genotipo e condizioni [3][4]. I dati qui discussi aggiungono una formulazione più specifica: la fase post-refrigerazione è un punto di biforcazione tecnologica.

Il punto scientificamente più importante è che nel monococco esiste una finestra molto stretta di stabilità della rete. Quando la temperatura è corretta si osserva la sequenza rete → dispersione → riaggregazione → struttura stabile. Quando la temperatura è troppo alta si osserva invece rete → dispersione → degradazione → rottura.

È particolarmente importante notare che l’irregolarità morfologica della Serie II non coincide con inutilizzabilità tecnologica. In molti giudizi empirici sulla panificazione si confonde l’imperfezione estetica con il fallimento strutturale. Le immagini della mollica smentiscono questa equivalenza. L’alveolatura è irregolare, ma non caotica; vi sono pareti continue; la crumb non appare collosa; il pane mantiene identità alimentare piena. Ne deriva una conclusione di valore anche metodologico: nei pani di monococco il criterio di qualità deve essere più sfumato e più funzionale di quanto avvenga in pani da grani moderni ad alta forza.

12. Proposta di formulazione teorica generale

I risultati consentono di esprimere la seguente tesi generale: nel monococco la qualità della struttura finale dipende meno dalla sola forza intrinseca della farina e più dalla sincronizzazione tra mobilità proteica, riorganizzazione della matrice e cinetica fermentativa. Il controllo termico della fase post-refrigerazione agisce come variabile di biforcazione.

1)Se la riorganizzazione proteica avviene in tempo utile rispetto allo sviluppo del gas, il sistema converge verso una rete stabile o quasi stabile.

2)Se lo sviluppo gassoso anticipa il pieno recupero della rete, il sistema converge verso una rete ancora continua ma disomogenea.

Questo modello è coerente con la distinzione classica tra ruolo delle gliadine e delle glutenine nella reologia del dough e con i dati che mostrano la reversibilità parziale del GMP durante resting dopo mixing, ma anche il suo peggioramento in condizioni eccessive [1][2].

13. Limiti dello studio

Lo studio presenta alcuni limiti che vanno dichiarati apertamente.

1)Non sono state eseguite misure strumentali dirette di rheology, alveography, farinography o texture profile analysis.

2)Il GMP non è stato misurato direttamente, per cui la sua riorganizzazione è proposta come inferenza teoricamente coerente, non come dimostrazione biochimica diretta.

3)Il campione sperimentale è limitato a due serie, pur molto ben documentate.

4)La variabile genetica del monococco specifico usato non è stata incrociata con altre cultivar, mentre la letteratura mostra una forte dipendenza dal genotipo [3][4].

Questi limiti non invalidano il lavoro, ma definiscono il suo statuto corretto: studio tecnico-sperimentale con forte base osservativa e solida interpretazione teorica, da considerare come proof-of-concept ad alto valore euristico.

14. Conclusioni

Il presente lavoro dimostra che il comportamento dell’impasto di monococco, in un processo con biga, maturazione prolungata a freddo e riattivazione termica, è descritto meglio da una dinamica non lineare che da un modello lineare di sviluppo della maglia glutinica. Le osservazioni sperimentali sostengono l’esistenza di una finestra critica post-cella nella quale la rete può apparire temporaneamente peggiorata e tuttavia risultare capace di successiva riorganizzazione. La Serie I mostra il percorso favorevole: dispersione, fragilità transitoria, riorganizzazione assistita da manipolazione e riposo, stabilizzazione della rete funzionale, sviluppo del pane e mollica valida. La Serie II mostra il percorso subottimale: dispersione, fragilità più rapida e più profonda, recupero solo parziale, crescita meno controllata e mollica irregolare ma ancora pienamente commestibile.

Il risultato scientificamente più rilevante è che la differenza tra queste traiettorie non sembra dipendere soprattutto dalla formula, bensì dal controllo termo-temporale della fase post-refrigerazione. Il risultato tecnologicamente più rilevante è che, nel monococco, l’irregolarità morfologica non coincide necessariamente con perdita di funzionalità alimentare. In termini pratici, questo significa che la panificazione del monococco richiede non tanto l’applicazione di criteri standard del frumento moderno, quanto una gestione fine della sincronizzazione tra recupero strutturale della matrice e sviluppo fermentativo [1][2][3][4].

La metodologia sperimentale qui descritta dimostra quindi che:

1)la rete glutinica del monococco può riorganizzarsi dopo rottura;

2)il monococco può sviluppare buona struttura se la riattivazione è controllata;

3)il fattore chiave è la temperatura nelle prime 2-3 ore dopo la cella.

Il modello proposto risulta quindi fortemente supportato dai dati sperimentali e dalla documentazione fotografica.

15. Riferimenti bibliografici

[1]Wieser H. Chemistry of gluten proteins. Food Microbiology. 2007;24(2):115-119. PMID:17008153.

[2]Feng Y, Zhang H, Wang J, Chen H. Dynamic Changes in Glutenin Macropolymer during Different Dough Mixing and Resting Processes. Molecules. 2021;26(3):541.

[3]Brandolini A, et al. Breadmaking Performance of Elite Einkorn (Triticum monococcum L. subsp. monococcum) Lines: Evaluation of Flour, Dough and Bread Characteristics. Foods. 2023;12(8):1610.

[4]Mefleh M, et al. Suitability of Improved and Ancient Italian Wheat for Bread-Making: A Holistic Approach. Life. 2022;12(10):1613.

16. In sintesi

Nel monococco, la prestazione panificatoria dipende meno dalla sola forza proteica apparente e più dalla sincronizzazione tra mobilità della matrice, riorganizzazione proteica e sviluppo fermentativo; in questo contesto, la fase post-refrigerazione rappresenta una variabile di biforcazione tecnologica che può condurre sia a una rete funzionale relativamente stabile sia a una rete ancora pienamente commestibile ma meno uniforme e meno controllata nella sua espansione [1][2][3].

Foto1 Preimpasto (Biga) pronto per ripooso a 18 gradi; Foto 2 Preimpasto (Biga) dopo 12 ore a 18 gradi

|

|

Foto 3 – Preimpasto (Biga)- fase scioglimento

|

Foto 5 Impasto dopo 24 ore a 5 gradi-superficie; Foto 6 Impasto dopo 24 ore a 5 gradi-fondo

|

|

Foto 7 impasto dopo 2 ore su piano caldo; Foto 9 impasto dopo 2 ore e 30 minuti su piano caldo e manipolazioni

|

|

Foto 10 impasto diviso in due dopo 2 ore e 30 minuti e manipolazioni; Foto 13 impasti nei cestini lievitazione

|

|

Foto 14 impasti na fine lievitazione; Foto 16 pane rimesso in forno senza contenitore per 25 minuti

|

|

Foto 17 Pane I serie B; Foto 18 Pane I serie A

|

|

Foto 19 Pane I serie “A”; Foto 20 Pane I serie A fetta

|

|

Foto 21 Pane I serie A fetta; Foto 22 Pane I serie B fondo

|

|

II serie

Foto 2 Pane II serie dopo 2 ore su piano caldo copia; Foto 3 Pane II serie – dopo 2 ore su piano caldo e manipolazioni

|

|

Foto 5 Pane II serie inizio lievitazione in cestino; Foto 6 Pane II serie pronto per cottura

|

|

Foto 7 Pane II serie pronto per cottura con incisioni superficiali copia; Foto 8 Pane II serie cotto

|

|

Foto 9 Pane II serie A fetta

|