1 – Antiossidanti e crusca del grano

Gli antiossidanti (presenti nella crusca) possono interagire con le proteine del glutine riducendo le reazioni di interscambio disolfuro-solfidrile, influenzando così l’aggregazione delle proteine del glutine. (Huang et al., 2018).

2 – Antiossidanti e crusca del grano

La crusca di frumento fornisce sia fibre alimentari che una grande varietà di sostanze che si ritiene siano biologicamente attive, come antiossidanti, fitoestrogeni o lignani (Pruckler et al., 2014).

3 – Interazione cisteina glutine

La cisteina (enzima) presente nel germe di grano esercita attività idrolizzante nei confronti del glutine.

4 – Durante la fase di maturazione avviene una parziale idrolisi dei peptidi del frumento.

Per quanto riguarda le proteine presenti negli impasti, è stato osservato che con la fase di maturazione avviene una parziale idrolisi dei peptidi del frumento, quali residui di proline e glutammine che sono responsabili dell’innesco della risposta autoimmune nei pazienti celiaci (Iancu et al., 2019).

5 – Il glutine e fermentazione utilizzando madri acide

In altri studi si è invece recentemente provato che il glutine viene completamente idrolizzato durante la fermentazione utilizzando madri acide, rendendo i prodotti derivati sicuri per il consumo da parte di individui celiaci.

6 – Prodotti fermentati da madri acide e sintomi da intestino irritabile

Correlato al disturbo della celiachia, è stato osservato che i prodotti fermentati da madri acide riescono a controllare e a ridurre i sintomi da intestino irritabile (Gobbetti et al., 2019).

7 – Hydrolysis and depolymerization of gluten proteins during sourdough fermentation

Hydrolysis and depolymerization of gluten proteins during sourdough fermentation were determined. Neutral and acidified doughs in which microbial growth and metabolism were inhibited were used as controls to take into account the proteolytic activity of cereal enzymes. Doughs were characterized with respect to cell counts, pH, and amino nitrogen concentrations as well as the quantity and size distribution of SDS-soluble proteins. Furthermore, sequential extractions of proteins and analysis by HPLC and SDS-PAGE were carried out. Sourdough fermentation resulted in a solubilization and depolymerization of the gluten macropolymer. This depolymerization of gluten proteins was also observed in acid aseptic doughs, but not in neutral aseptic doughs. Hydrolysis of glutenins and occurrence of hydrolysis products upon sourdough fermentation were observed by electrophoretic analysis. Comparison of sourdoughs with acid control doughs demonstrated that glutenin hydrolysis and gluten depolymerization in sourdough were mainly caused by pH-dependent activation of cereal enzymes.

…….Il confronto tra impasti a lievitazione naturale e impasti a controllo acido ha dimostrato che l’idrolisi della glutenina e la depolimerizzazione del glutine nella pasta madre erano principalmente causate dall’attivazione pH-dipendente degli enzimi dei cereali…….Gluten hydrolysis and depolymerization during sourdough fermentation Claudia Thiele, Simone Grassl, Michael Gänzle PMID: 14995138 ; DOI: 10.1021/jf034470z

8 – Gluten breakdown by lactobacilli and pediococci strains isolated from sourdough. C L Gerez, G C Rollán, G F de Valdez; PMID: 16620203; DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01889.x

9 – Proteolytic activity and reduction of gliadin-like fractions by sourdough lactobacilli

G Rollán, M De Angelis, M Gobbetti, G F de Valdez; PMID: 16313422; DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02730.x

Abstract

Aims: To characterize the peptide hydrolase system of Lactobacillus plantarum CRL 759 and CRL 778 and evaluate their proteolytic activity in reducing gliadin-like fractions.

Methods and results: The intracellular peptide hydrolase system of Lact. plantarum CRL 759 and CRL 778 involves amino-, di- (DP), tri- (TP) and endopeptidase activities. These peptidases are metalloenzymes inhibited by EDTA and 1,10-phenanthroline and stimulated by Co2+. DP and TP activities of Lact. plantarum CRL 759 and CRL 778, respectively, were completely inhibited by Cu2+. Lactobacillus plantarum CRL 778 showed the highest proteolytic activity and amino acids release in fermented dough. The synthetic 31-43 alpha-gliadin fragment was hydrolysed to 36% and 73% by Lact. plantarum CRL 778 and CRL 759 respectively.

Conclusions: Lactobacillus plantarum CRL 759 and CRL 778 have an active proteolytic system, which is responsible for the high amino acid release during sourdough fermentation and the hydrolysis of the 31-43 alpha-gliadin-like fragment.

Significance and impact of the study: This work provides new information of use when obtaining sourdough starters for bread making. Moreover, knowledge regarding lactobacilli capable of reducing the level of gliadin-like fractions, a toxic peptide for coeliac patients, has a beneficial health impact.

Note:

A – Crusca di grano I parte (https://glutenlight.eu/?s=bran+composition)

B – Il germe del frumento contiene α-tocoferolo, vitamine, minerali, fitochimici e proteine di alto valore, trigliceridi e lipasi e attività di lipossigenasi. La presenza di questi elementi purtroppo favoriscono l’ossidazione dei grassi e quindi la formazione di off-flavour nella fase di stoccaggio e nella preparazione di panificati. Questo però non avviene se viene utilizzata la lievitazione con lievito madre, perché quest’ultima è capace di disattivare l’attività delle lipasi consentendo l’uso del germe nei lievitati.

In entrambe le specie la cariosside si distingue in:

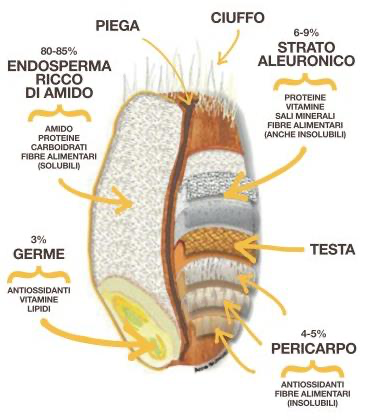

Endosperma o mandorla amilifera: è costituito da due parti: lo strato aleuronico e l’endosperma amilifero. Lo strato aleuronico che viene perso con la crusca, è lo strato più esterno monostratificato, ricco di proteine, grassi, sostanze minerali, vitamine ed enzimi. L’endosperma amilifero rappresenta l’80-85% del peso dell’intera cariosside ed è costituito da cellule poliedriche allungate che contengono i granuli di amido. Tegumenti esterni: sono il 7-8 % del chicco e costituiscono la crusca. Sono costituiti da tre strati: il pericarpo, lo spermoderma e il perisperma. Il pericarpo è l’involucro esterno ed è formato dall’epicarpo e da tre strati di cellule (intermedie, incrociate e tubolari). Lo spermoderma è l’involucro che serve a proteggere il seme vero e proprio. Il perisperma o strato ialino separa l’ultimo strato dello spermoderma da quello delle cellule aleuroniche. Essi vanno a formare la crusca che normalmente viene allontanata durante la macinazione. Da un punto di vista morfologico, hanno la funzione di proteggere l’embrione e le sostanze nutritive ad esso necessarie durante il primo periodo di germinazione. Germe o embrione: costituisce l’apparato germinativo del chicco e contiene lipidi, vitamine del gruppo B e, minerali e proteine (Surget et al., 2005 e Carrai, 2010)

Figura 2: struttura della cariosside del frumento (Surget et. al.,2005)

Le fasi della molitura devono essere precedute da una fase di pulitura e di condizionamento dei cereali. Nella prima fase lo scopo è quello di eliminare i materiali estranei come pietre, sassi e paglia. Invece, il condizionamento consiste nel ridurre, attraverso l’umidificazione, la friabilità che è presente nei tegumenti allo stato secco. Inoltre, rende più friabile l’endosperma e ne facilita la separazione dai tegumenti. L’umidità iniziale nel frumento tenero è del 10-12% mentre l’umidità finale dopo il condizionamento è del 15-16% aumentando in questa fase la possibilità di fenomeni di germinazione e crescita microbica.

I Sottoprodotti dell’industria molitoria I prodotti e i sottoprodotti della macinazione del frumento, sottoposto alle varie fasi di macinazione e conseguente abburattamento, si possono dunque suddividere in:

– Farina: 75%

SOTTOPRODOTTI

Farinaccio: 2,5-3% dimensioni di circa 200 µm

Crusca: 20-22% insieme a cruschello e tritello. Ha una dimensione di circa 900-600 µm.

Cruschello: dimensione di 340 µm

Tritello: simile al cruschello, ma con parti più triturate e con più parti farinose attaccate

Farinette: 0,2-2%.

Fonte: ALMA MATER STUDIORUM – UNIVERSITÀ DI BOLOGNA CAMPUS DI CESENA SCUOLA DI AGRARIA E MEDICINA VETERINARIA CORSO DI LAUREA MAGISTRALE IN SCIENZE E TECNOLOGIE ALIMENTARI-

TITOLO DELLA TESI: Isolamento e identificazione di lieviti e batteri lattici da sottoprodotti dell’industria molitoria e loro impiego nella formulazione di prefermenti da utilizzare in panificazione. Tesi in Microbiologia delle fermentazioni.

Presentata da Alessio Gigli; Relatore Prof.ssa Rosalba Lanciotti; Correlatori Dott. Lorenzo Siroli Dott.ssa Samantha Rossi.