Mixture of grains (evolutive grain): no thanks!

“Ma di che si tratta esattamente? Una popolazione evolutiva non è altro che una mescolanza di tantissime varietà diverse della stessa specie. Un concetto tanto semplice, quanto concretamente utile: Questi miscugli servono a far fronte al cambiamento climatico grazie alla loro capacità di evolversi nel tempo. Proprio per questa loro capacità Ceccarelli preferisce chiamarle popolazioni evolutive, e non miscugli come si fa spesso. Vi faccio un esempio concreto: nel 2008 mentre lavoravo ad Aleppo ho mescolato un migliaio di tipi di semi di orzo e li ho portati ad alcuni agricoltori in cinque paesi diversi: Siria, Algeria, Eritrea, Giordania e Iran. Il risultato è stato subito un raccolto abbondante, che poi è stato distribuito ad altri agricoltori, e le sementi così selezionate sono state diffuse. L’anno successivo ho fatto lo stesso con frumento duro (mescolando 700 tipi diversi) e con il frumento tenero (mescolando 2000 tipi diversi). Con gli anni queste tre popolazioni si sono moltiplicate, hanno viaggiato per tutto il Medio Oriente e nel 2010 sono arrivate e hanno cominciato a diffondersi in Italia. Una diffusione avvenuta spontaneamente tra gli agricoltori con il semplice passaparola. I vantaggi. Si tratta di miglioramento genetico partecipativo-evolutivo, facilmente spiegabile attraverso la teoria dell’evoluzione, secondo cui coltivando una popolazione evolutiva, ci si mette al riparo da malattie ed erbe infestanti nuove o cambiamenti climatici perché tra gli individui di una popolazione ce ne sarà sempre una parte che riuscirà a cavarsela. Non solo, con le popolazioni evolutive si evita di sottostare al monopolio dei semi e all’impoverimento dei raccolti e della dieta quotidiana. “ Fonte: https://www.gamberorosso.it/notizie/articoli-food/grano-evolutivo-storia-e-vantaggi-del-miscuglio/ intervista al Dott. Salvatore Ceccarelli.

The consumer demand is increasingly oriented to knowing what they put on the plate, or rather to have the possibility to know the whole product chain and its characteristics. The wine and oil supply chain, to cite just two important examples, testify to the importance of complete and possibly exhaustive information, which is also the key, together with the quality, of the success of the most famous products. With wheat do we want to walk this path backwards? Do we eat what the field produces as mother nature decides?

Obviously I am not referring to the technique of hybridizing two or more grains / varieties with the specific purpose of obtaining a new one with certain characteristics (more resistant to diseases, more suitable for certain climates, more suitable for pasta, etc.): this technique presents the undoubted advantages of knowing what we want and how to obtain it and it is widely used and is largely suitable for achieving the advantages ascribed to the mixing technique. The seeds monopoly, on the other hand, must be fought with appropriate legislative limitations. The impoverishment of the crops and the diet is obtainable by using the immense wealth of the “ancient” grains. With the mixture of grains we will have a grain that will show differences from time to time for: • The gluten index which is very important for knowing the tenacity of “gluten” and therefore its digestibility. • The percentage of gluten that is important for the same reason mentioned above. • Tolerability which is linked to the qualitative and quantitative presence of the gluten-resistant portion of the gastro-intestinal digestion which in some subjects causes gluten sensitivity in others and which, in any case, is a further indicator of digestibility in the broad sense. • The possible presence of the gluten fraction responsible for wheat allergy. • The rheological characteristics that define the use of wheat: for pasta, for bread, for pizza, etc. Does it seem little to you? Diet impoverishment too! We end up falling into the most uncertain and foggy diet possible! Unless you believe that mother nature whatever it produces is certainly good for us! Regarding tolerability, there are many studies that have highlighted the difference – also strong – difference in the grains of the gluten fraction resistant to gastro intestinal digestion:

- “Per quanto riguarda i peptidi immunogenici il contenuto maggiore è stato quello registrato nel frumento comune, ovvero nel frumento tenero. Il contenuto medio era di 524 mg/kg, da un minimo di 240 mg/kg di Blasco fino a un massimo di 829 mg/kg di grano del miracolo. Di poco inferiori sono le quantità registrate nelle specie tetraplodi, ovvero farro medio o dicocco e nel frumento duro. In media il contenuto di questi peptidi era, per il frumento duro, di 457 mg/kg, con contenuto minimo registrato nell’Odisseo (208 mg/kg) e un contenuto massimo registrato nel Senatore Cappelli (840 mg/kg). Nel farro dicocco il contenuto medio rilevato è stato di 421 mg/kg, dai 247 mg/kg del farro della Garfagnana coltivato a Parma ai 572 mg/kg del farro della Garfagnana coltivato a Bologna. I contenuti più bassi in assoluto dei peptidi immunotossici sono stati rilevati nel farro piccolo o monococco e nello spelta. Il contenuto medio rilevato nel farro monococco è stato di 166 mg/kg, con il contenuto minimo di 137 mg/kg per ID331 coltivato a Parma e il contenuto massimo, sempre nella stessa varietà, cresciuta a Bologna di 236 mg/kg. Nello spelta il contenuto medio è stato di 225 mg/kg, dal minimo di 63 mg/kg di Rouquin coltivato secondo gli standard dell’agricoltura biologica a Parma al massimo di 436 mg/kg di Rouquin coltivato secondo gli standard dell’agricoltura convenzionale sempre a Parma. Ovviamente, nonostante le quantità in queste due specie sono risultate essere inferiori rispetto alle altre specie, non si può affermare che si tratta alimenti sicuri per i celiaci.

- Per quanto riguarda i peptidi tossici il contenuto più basso è quello rilevato nello spelta, mentre il contenuto più alto registrato è stato quello del farro monococco ID331. CONFRONTO TRA VARIETÀ ANTICHE E MODERNE DI FRUMENTI ANCHE IN RELAZIONE A FENOMENI DI INTOLLERANZA ALIMENTARE. Tesi di laurea di Laura Kerer. Relatore Prof. Fabio Veronesi Correlatore Dott. Renzo Torricelli. Anno Accademico 2016-2017. UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PERUGIA Dipartimento di Scienze Farmaceutiche Corso di Laurea in Scienze dell’alimentazione e della nutrizione umana”.

The analyzes reported in the aforementioned study refer to the quantitative detection of the “toxic fraction” but the qualitative analysis of these fractions is equally important since it can be very different. The einkorn (monococcum wheat) ID331 cited, for example, is perhaps the wheat with the highest tolerability because it does not have the peptide 31 mer which is the most active among the toxic peptides and does not have the 33mer which is the most active one among the immunogenic ones because the monococcum wheat has the genome AA and the 33 mer is coded in the genome DD that characterizes the common bread wheat. Furthermore, another important element is the type of gluten that a grain possesses: shape and disposition of the amino acids that make up the peptides. (1) Einkorn has a “different” gluten from soft wheat and therefore has a higher digestibility and tolerability. (2)

(Protective effects of ID331 Triticum monococcum gliadin on in vitro models of the intestinal epithelium. Giuseppe Jacomino et altri 2016.

Highlights: ID331 gliadins do not enhance permeability and do not induce zonulin release. ID331 gliadins do not trigger cytotoxicity or cytoskeleton reorganization. ID331 gastrointestinal digestion releases ω(105–123) bioactive peptide. ω(105–123) exerts a protective action against the toxicity induced by T. aestivum)”.

“On the other hand, a subsequent paper investigating how in vitro gastro-intestinal digestion affects the immune toxic properties of gliadin from einkorn (compared to modern wheat), demonstrated that gliadin proteins of einkorn are sufficiently different from those of modern wheat, thereby determin- ing a lower immune toxicity following in vitro simulation of human digestion. (Suligoj T, Gregorini A, Colomba M, Ellis HJ, Ciclitira PJ. Evaluation of the safety of ancient strains of wheat in coeliac disease reveals heterogeneous small intestinal T cell responses suggestive of coeliac toxicity. Clin Nutr 2013;32:1043–9)”.

The rheological characteristics that define the use of wheat (for pasta, for bread, for pizza, etc.) are a very important element for industry and craftsmen who wish, indeed they want, a product to be worked “constant in characteristics” and not different from time to time as it would with a spontaneous result, so as not to have to re-set the working cycle and be able to offer a recognizable product. I imagine the joy of the industry or the bakery that is holding a “flour” that behaves differently every time! For pasta, for example, the content of high molecular weight glutenins is important. “During the last half of the past century one of the main goals of breeding programs in Mediterranean environments was the release of durum wheat cultivars with high quality standards (Subira et al., 2014). An increase in pasta-making quality during the 20th century in durum wheat cultivars released in Italy was reported by De Vita et al. (2007) due to the incorporation of favorable gluten protein alleles in modern cultivars, such as the HMW-GS 7 + 8 allele encoded by the Glu-B1 locus. Subira et al. (2014)”.

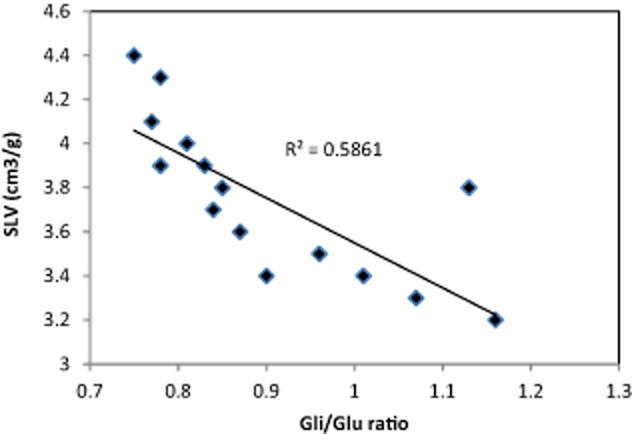

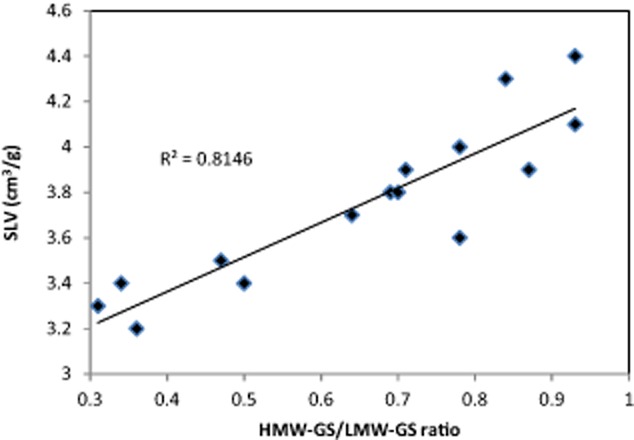

For bread: “The study evidently suggests that higher SLV (specific loaf volume) was obtained from wheat varieties having lower gliadin/glutenin and higher HMW‐GS/LMW‐GS ratio. R/E (resistance/extensibility) also exhibited a significant correlation (r = 0.81) with the SLV. This observation is consistent with the widely held view that a balance of elasticity and viscosity is essential for good bread‐making performance of wheat varieties.

Effects of Gliadin/Glutenin and HMW‐GS/LMW‐GS Ratio on Dough Rheological Properties and Bread‐Making Potential of Wheat Varieties

Vandana Dhaka B.S. Khatkar First published: 03 March 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfq.12122”.

I would prefer, therefore, to continue, instead, on the road of the realization of the “identity card” of the product, whether it is wheat, flour or the end product with a description of all the steps of the supply chain or, at least, of those more significant.

Depeenings

1. Gluten and “toxic” fractions (part I)

2. Tolerability of monococcum wheat

Back