Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a complex and multifactorial disorder that cannot be explained by a single pathogenic mechanism. In recent years, increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) has received considerable attention as a potential contributor to IBS pathophysiology. However, current scientific evidence indicates that barrier dysfunction affects only a subset of patients rather than representing a universal feature of the condition. Increased intestinal permeability is more frequently observed in diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) and post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS), whereas many patients exhibit a structurally intact intestinal barrier. In these cases, symptoms are more accurately attributed to alterations in the gut–brain axis, visceral hypersensitivity, disordered intestinal motility, and gut microbiota dysbiosis. An integrated understanding of these mechanisms is essential to move beyond reductionist models and to guide personalized therapeutic strategies.

Keywords

irritable bowel syndrome, IBS, intestinal permeability, leaky gut, IBS-D, post-infectious IBS, gut barrier, tight junctions, gut-brain axis, visceral hypersensitivity, gut microbiota, functional gastrointestinal disorders, chronic abdominal pain, low-grade inflammation, personalized IBS treatment

1. Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders, characterized by recurrent abdominal pain associated with changes in bowel habits, in the absence of identifiable structural abnormalities. Over the past two decades, the traditional view of IBS as a purely “functional” disorder has been progressively replaced by a more comprehensive model that integrates neurobiological, immune, microbial, and mucosal barrier factors.

Within this evolving framework, increased intestinal permeability—commonly referred to as “leaky gut”—has been proposed as a central mechanism in IBS pathogenesis. While this hypothesis has gained substantial attention, accumulating evidence suggests a more nuanced reality: increased permeability is present only in a subset of IBS patients and does not constitute a defining feature of the syndrome as a whole.

2. Evidence of Altered Intestinal Permeability in IBS

Numerous clinical and experimental studies have assessed intestinal barrier function in IBS using permeability tests (e.g., lactulose/mannitol ratio), urinary and plasma biomarkers, mucosal biopsies, and molecular analyses of tight junction proteins.

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that:

A significant but non-majority proportion of IBS patients exhibits increased intestinal permeability;

Barrier dysfunction is more commonly observed in the colon, although small intestinal involvement may occur in specific subgroups;

Increased permeability is not stable over time and may fluctuate in response to prior infections, dietary factors, psychological stress, and microbiota composition.

These findings indicate that intestinal barrier dysfunction represents an important pathogenic mechanism in IBS, but not an exclusive or universal one.

3. Differences Among IBS Subtypes

The heterogeneity of IBS becomes particularly evident when examining its clinical subtypes:

IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant IBS): This subtype is most frequently associated with increased intestinal permeability. Alterations in tight junction proteins and enhanced immune exposure to luminal antigens have been consistently reported.

Post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS): PI-IBS represents one of the strongest models linking IBS to barrier dysfunction. Following acute gastroenteritis, some patients develop chronic symptoms associated with increased permeability, low-grade mucosal inflammation, and mast cell activation.

IBS-C (constipation-predominant IBS): In most studies, intestinal permeability in IBS-C patients is comparable to that of healthy controls.

IBS-M (mixed subtype): Barrier function appears most consistently preserved in this group.

These differences underscore the absence of a single biological phenotype underlying IBS.

4. Molecular Mechanisms of Barrier Dysfunction

In IBS patients with increased permeability, several structural and functional alterations of the intestinal epithelial barrier have been documented, including:

Reduced expression or disorganization of tight junction proteins such as ZO-1, occludin, and claudins;

Increased paracellular passage of luminal molecules and antigens;

A correlation between the degree of barrier impairment and the severity of abdominal pain.

Loss of epithelial integrity facilitates contact between luminal antigens (bacterial or dietary) and the mucosal immune system, contributing to low-grade inflammatory responses.

5. Interaction Between Intestinal Permeability, Immune System, and Microbiota

In IBS subgroups characterized by barrier dysfunction, increased permeability may initiate a pathogenic cascade involving:

Activation of mast cells and other immune cells within the lamina propria;

Release of inflammatory and neuroactive mediators;

Sensitization of enteric nerve endings.

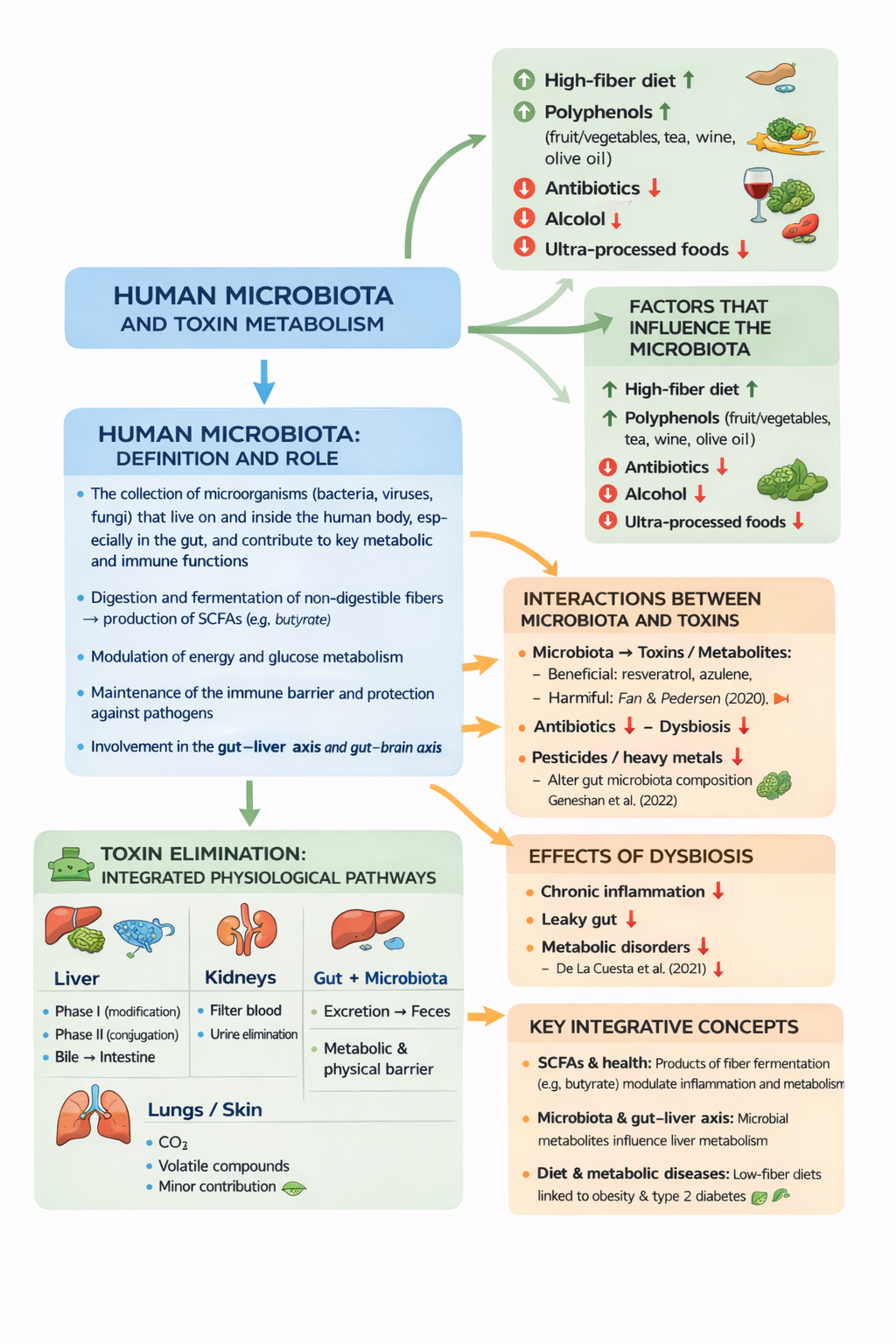

The gut microbiota plays a central role in this process. Qualitative and functional alterations of microbial communities can both contribute to barrier dysfunction and amplify immune and neural responses. Nevertheless, these mechanisms are not present in all IBS patients, reinforcing the concept of biological heterogeneity.

6. IBS Without Increased Intestinal Permeability

A crucial and often underestimated aspect of IBS is that many patients exhibit a structurally intact intestinal barrier. This is well documented in IBS-C and IBS-M subtypes, but also applies to a proportion of IBS-D patients.

In such cases, the leaky gut model alone is insufficient to explain symptom generation.

7. Alternative Mechanisms Independent of Permeability

7.1 Gut–Brain Axis Dysfunction

IBS is currently classified as a disorder of gut–brain interaction. Altered bidirectional communication between the enteric nervous system and the central nervous system can generate pain, urgency, and bowel habit changes in the absence of mucosal damage.

7.2 Visceral Hypersensitivity

Many IBS patients exhibit a reduced pain threshold to physiological intestinal stimuli. This phenomenon is attributed to:

Peripheral neural sensitization;

Central amplification of nociceptive signaling.

7.3 Altered Intestinal Motility

Disruptions in intestinal motor patterns may account for diarrhea, constipation, or alternating bowel habits without involving epithelial barrier dysfunction.

7.4 Dysbiosis Independent of Barrier Damage

Gut microbiota alterations may influence fermentation, gas production, bile acid metabolism, and neuroendocrine signaling even when intestinal permeability remains normal.

8. Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Recognizing the heterogeneity of IBS has important clinical consequences:

In IBS-D and PI-IBS patients with documented increased permeability, interventions targeting barrier function (e.g., low-FODMAP diet, microbiota modulation, mucosal protective strategies) may be particularly beneficial;

In patients with normal permeability, therapeutic approaches focused on the gut–brain axis, visceral sensitivity modulation, and stress management are likely more appropriate.

A personalized approach is therefore essential.

9. Conclusions

IBS is a multifactorial and biologically heterogeneous condition. Increased intestinal permeability represents a documented and clinically relevant pathogenic mechanism, but it is not universal. In many patients, symptoms arise from neurofunctional, motor, or microbial alterations in the presence of an intact intestinal barrier.

An integrated perspective allows clinicians and researchers to move beyond reductionist models and to develop more effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

The inflammatory, neurofunctional, microbial, and barrier-related mechanisms discussed here are explored in greater detail in the related articles referenced below.

Commented Bibliographic References (for Further Reading)

1. Camilleri M. et al. – Review on IBS and intestinal barrier function

A critical analysis of permeability alterations across IBS subtypes, emphasizing their non-universality.

2. Bischoff S.C. et al. – Intestinal permeability: mechanisms and clinical relevance

A foundational reference on molecular mechanisms of barrier function and clinical implications.

3. Spiller R., Garsed K. – Post-infectious IBS . Describes PI-IBS as a key model linking low-grade inflammation and increased permeability.

4. Barbara G. et al. – Mast cells and IBS. Seminal work on mast cell involvement in visceral pain and hypersensitivity.

5. Ford A.C. et al. – Systematic reviews on IBS pathophysiology

Integrated overview of microbiota, motility, and gut–brain axis mechanisms.

6. Drossman D.A. – Disorders of gut–brain interaction. A cornerstone reference framing IBS within modern gut–brain interaction paradigms.

The different mechanisms discussed—inflammatory, neuro-functional, microbial, and barrier-related—are examined separately in the related articles.