ABSTRACT

IBS is one of the most common types of functional bowel disorder. Increasing attention has been paid to the causative role of food in IBS. Food ingestion precipitates or exacerbates symptoms, such as abdominal pain and bloating in patients with IBS through different hypothesised mechanisms including immune and mast cell activation, mechanoreceptor stimulation and chemosensory activation. Wheat is regarded as one of the most relevant IBS triggers, although which component(s) of this cereal is/are involved remain(s) unknown. Gluten, other wheat proteins, for example, amylase-trypsin inhibitors, and fructans (the latter belonging to fermentable oligo-di-mono-saccharides and polyols (FODMAPs)), have been identified as possible factors for symptom generation/exacerbation. This uncertainty on the true culprit(s) opened a scenario of semantic definitions favoured by the discordant results of double-blind placebo-controlled trials, which have generated various terms ranging from non-coeliac gluten sensitivity to the broader one of non-coeliac wheat or wheat protein sensitivity or, even, FODMAP sensitivity. The role of FODMAPs in eliciting the clinical picture of IBS goes further since these short-chain carbohydrates are found in many other dietary components, including vegetables and fruits. In this review, we assessed current literature in order to unravel whether gluten/wheat/FODMAP sensitivity represent ‘facts’ and not ‘fiction’ in IBS symptoms. This knowledge is expected to promote standardisation in dietary strategies (gluten/wheat-free and low FODMAP) as effective measures for the management of IBS symptoms.

Extract from study:

WHEAT SENSITIVITY

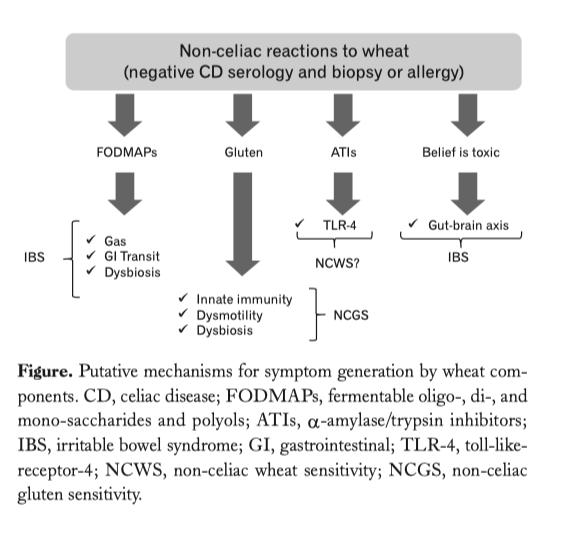

Wheat is considered one of the foods known to evoke IBS symptoms. However, which component(s) of wheat is/are actually responsible for these clinical effects still remain(s) an unsettled issue. The two parts of wheat that are thought to have a mechanistic effect comprise proteins (primarily, but not exclusively, gluten) and carbohydrates (primarily indigestible short-chain components, FODMAPs). Two distinct views characterise the clinical debate: one line identifies wheat proteins as a precipitating/perpetuating factor leading to symptoms, while the other believes that FODMAPs are the major trigger for IBS.

The controversy over nomenclature

If gluten is a major trigger for IBS, it expands the gluten-related disorders by adding a new entity now referred to as non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS). Indeed, coeliac disease-like abnormalities were reported in a subgroup of patients with IBS many years ago. A recent expert group of researchers reached unanimous consensus attesting the existence of a syndrome triggered by gluten ingestion. This syndrome recognises a wide spectrum of symptoms and manifestations including an IBS-like phenotype, along with an extra-intestinal phenotype, that is, malaise, fatigue, headache, numbness, mental confusion (‘brain fog’), anxiety, sleep abnormalities, fibromyalgia-like symptoms and skin rash. In addition, other possible clinical features include gastroesophageal reflux disease, aphthous stomatitis, anaemia, depression, asthma and rhinitis. Symptoms or other manifestations occur shortly after gluten consumption and disappear or recur in a few hours (or days) after gluten withdrawal or challenge. A fundamental prerequisite for suspecting NCGS is to rule out all the established gluten/wheat disorders, comprising coeliac disease (CD), gluten ataxia, dermatitis herpetiformis and wheat allergy. The major issue not addressed by the consensus opinion was that gluten is only one protein contained within wheat. Other proteins, such as amylase-trypsin inhibitors (ATIs), are strong activators of innate immune responses in monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells. Furthermore, wheat germ agglutinin, which has epithelial-damaging and immune effects at very low doses at least in vitro, might also contribute to both intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations of NCGS. Consequently, a further development of this research field led to suggestions of a broader term, non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS). The problems with this term are twofold. First, rye and barley may be inappropriately excluded. Second, the term will refer to any wheat component that might be causally related to induction of symptoms and, therefore, will also include fructans (FODMAPs). It will then have a very nonspecific connotation in IBS. A more correct term would then be non-coeliac wheat protein sensitivity (NCWPS) since this does not attribute effects to gluten without evidence of such specificity, eliminates the issue of fructan-induced symptoms and avoids the unknown contribution of rye and barley proteins to the symptoms. Both NCGS, the currently accepted term, and NCWPS will be used subsequently in this paper.

Read More