(In-depth article 4 of: Genetic potential and processing conditions in determining gluten strength, digestibility, and immunogenicity)

When creating a new wheat cultivar, breeders aim to obtain strong wheats.

In breeding, this becomes central because:

-

if you want to increase the probability of obtaining “strong” lines, you select parents with favorable alleles/subunits;

-

then, in the progeny, you use rapid tests (and increasingly molecular markers / rapid proteomics) to choose the best lines.

Clear examples:

-

Near-isogenic lines (NILs) or lines with targeted deletions: these are specifically used to isolate the effect of a single HMW-GS on dough strength/elasticity. A recent study shows that the absence of individual HMW-GS reduces elasticity/strength and alters alveographic parameters. (ScienceDirect)

-

Studies on populations (DH lines) comparing combinations of HMW-GS and their effect on quality traits: they show that the effect is not only “presence/absence,” but also depends on interactions among subunits. (PLOS)

-

Accelerated screening of breeding lines with rapid gluten-strength tests: useful because breeding programs must evaluate thousands of samples. (MDPI)

Wheats with lower genetic potential but greater ability to create new bonds.

The “genetic potential” (subunits, cysteines, fraction ratios) sets an upper limit: if certain structural components are missing, you cannot build a large network from nothing.

However, the “capacity to express” that potential also depends on factors that vary among varieties and lots: accessibility of reactive groups, thiol–disulfide exchange kinetics, initial distribution of polymeric fractions, etc.

This is why, in practice, proxies such as GMP and polymeric fraction analyses are also used to understand how much the network actually develops. (ResearchGate)

These biological differences translate into the possibility of using specific genetic and proteomic markers as predictive tools.

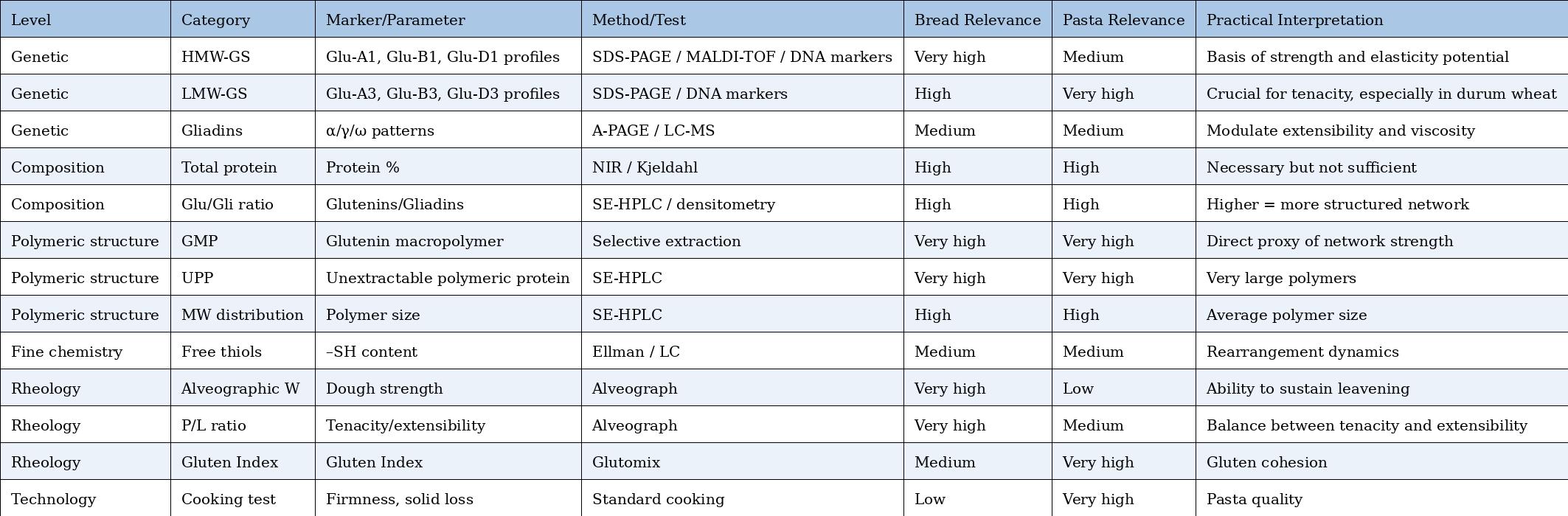

Comparative Table – Markers and Tests for Bread vs. Pasta

Practical markers (also usable in professional contexts)

1) HMW-GS profile at Glu-1 loci (Glu-A1 / Glu-B1 / Glu-D1)

-

What it is: which HMW-GS subunits are present (e.g., at Glu-D1: 5+10 vs 2+12).

-

Why it matters: some combinations are repeatedly associated with better rheological and baking properties; in particular, allele 5+10 (Glu-D1d) and 17+18 (Glu-B1i) are often reported among the most “effective.” (PMC)

-

How it is measured (practical): SDS-PAGE; in screening contexts also MALDI-TOF. (PMC)

2) “Polymeric vs monomeric” ratio (P/M) or proportion of high-MW polymers (SE-HPLC / extractability)

-

What it is: how much protein is in polymeric form (glutenins, especially high MW) relative to smaller/monomeric fractions.

-

Why it matters: higher polymeric fraction (and especially large polymers) → greater potential elastic “framework.”

-

How it is measured: SE-HPLC (size distribution) or extractability proxies (SDS-soluble vs SDS-insoluble).

3) GMP / UPP (glutenin macropolymer; unextractable polymeric protein)

-

What it is: fraction of very large polymers (often SDS-insoluble) considered tightly linked to network strength.

-

Why it matters: one of the most widely used proxies for “how much polymeric network” can be built and expressed.

4) Free thiol (–SH) content and redox state

-

What it is: how many –SH groups are free (and therefore potentially involved in thiol–disulfide exchange).

-

Why it matters: it does not indicate “how high W will be,” but helps explain disulfide reorganization dynamics (expressibility of potential), i.e., how easily the network can remodel.

Documented examples

A) Example (bread): cultivars named in a study with moderate-to-strong gluten

A study on Indian varieties combining markers and rheological evaluations reports that only four varieties among those analyzed combined high protein content and moderately strong gluten: K307, DBW39, NI5439, DBW17. (PMC)

Note: this is a “named” example within a specific study (useful as proof that literature lists cultivars), but obviously relative to the germplasm and context of that work.

B) Example (Italy, durum): named varieties and differences in composition (glutenins/gliadins)

In a study on durum wheat genotypes, varieties such as Svevo and Saragolla are reported (higher in glutenins and lower in gliadins in the considered set) and Cappelli shows opposite behavior in the reported comparison. (doi.org).

This type of evidence links starting composition (fraction ratios) to a potentially more or less favorable profile for “strong gluten.”

C) Example (Italy, durum): technological quality and W in “old cultivars”

A study evaluates “historical” durum cultivars with technological measurements including W (alveograph) to discuss whether the quality of old cultivars is comparable to modern ones. (PMC)

(The study is useful because it shows that the question “which cultivars have high W” is addressed experimentally on real varietal sets.)

Existing “strong” cultivars and new ones

-

Screening of existing cultivars: HMW-GS genotyping/profiling and measurement of rheology or polymeric proxies. (PMC)

-

Breeding (hybridization/new lines): the same scheme is used as a selection criterion, but it does not originate “only” there. (PMC)

SOFT wheats (bread) — cultivars with HMW-GS profiles associated with high quality

Examples from studies on glutenin alleles and profiles associated with quality traits (mainly for bread) (ResearchGate)

|

Cultivar/Genotipo |

Combinazione HMW-GS Glu-1 |

Nota sul potenziale di qualità |

Fonte |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Genotipo con “1, 7+9, 5+10” |

1 (Glu-A1), 7+9 (Glu-B1), 5+10 (Glu-D1) |

Combinazione associata a migliori qualità di grano (contenuto proteico, WGC ecc.) |

Wang et al. (2024) (MDPI) |

|

Genotipo con “1, 7, 5+10” |

1, 7, 5+10 |

Effetti positivi su parametri qualitativi del grano |

Wang et al. (2024) (MDPI) |

|

Genotipo con “1, 14+15, 2+12” |

1, 14+15, 2+12 |

Buone correlate a qualità (proteine, WGC) |

Wang et al. (2024) (MDPI) |

|

Genotipo con “1, 6+8, 5+10” |

1, 6+8, 5+10 |

Correlazione positiva con qualità |

Wang et al. (2024) (MDPI) |

|

GW-273 |

profilo HMW-GS non esplicitato |

Glu-1 score alto (10/10), indicativo di superiori caratteristiche di impasto per pane |

Patil (2015) (Tandfonline) |

|

GW-322 |

profilo HMW-GS non esplicitato |

Glu-1 score elevato (10/10) |

Patil (2015) (Tandfonline) |

What do these data indicate?

-

HMW-GS allele combinations with 5+10 and certain Glu-B1 variants (such as 7+9, 14+15) are frequently associated with better qualitative parameters (e.g., WGC, dough performance) in studies on many soft wheat genotypes.

-

Some genotypes have very high “Glu-1 scores” (≈ 9–10), a phenomenon correlated with higher genetic potential for strong gluten quality. (ResearchGate)

DURUM wheats (pasta / durum bread) — examples and considerations (protein profile and quality)

For durum wheat (Triticum durum), the literature is more variable and often focuses on local collections or genetic variability rather than on specific cultivar names “classified by gluten quality.” However, useful documentation exists on glutenin allelic profiles in durum lines and their relationship with quality traits (including uses other than pasta). (Springer Nature Link)

Creso (historical Italian durum wheat cultivar)

Cultivar obtained in the 1970s through mutagenesis and selection, widely used as a parent in breeding programs to combine yield, adaptation, and technological quality.

Scientific references:

-

De Vita, P., et al. (2007). Genetic improvement effects on yield stability in durum wheat cultivars grown in Italy. Euphytica.

-

De Vita, P., et al. (2010). Effects of genetic improvement on protein content and gluten quality in durum wheat grown in Italy. European Journal of Agronomy.

-

Laidò, G., et al. (2013). Genetic diversity and population structure of durum wheat (Triticum durum) landraces and cultivars using SSR markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution.

Why relevant here:

Creso often appears as a parent or reference in studies analyzing progressive improvement of parameters such as protein content, gluten index, and dough characteristics, showing how breeding has increased technological quality in durum wheat.

Simeto (modern Italian durum wheat cultivar)

Variety selected in Italy and widely cultivated, used as a reference for good semolina quality and balanced technological performance.

Scientific references:

-

De Vita, P., et al. (2007). Euphytica.

-

Troccoli, A., et al. (2000). Variation in grain quality traits among durum wheat cultivars grown in southern Italy. Cereal Chemistry.

-

Ficco, D. B. M., et al. (2014). Genetic variability in quality traits of durum wheat for pasta making. Journal of Cereal Science.

Why relevant here:

Simeto is frequently included in comparisons among modern cultivars, showing good levels of protein, gluten index, and semolina quality, parameters that can also be linked to glutenin composition.

|

Varietà / linea (durum) |

Nota qualitativa / genotipica |

Fonte |

|---|---|---|

|

Varietà marocchine (Henkrar et al.) |

Diverse combinazioni alleliche HMW-GS correlate a qualità di trasformazione |

Henkrar et al., 2017 |

|

Isly, Massa, Anouar, Sboula, Chaoui |

Profili variabili di glutenine HMW |

Henkrar et al., 2017 |

|

Creso |

Cultivar storica, genitore chiave nel breeding italiano; miglioramento progressivo di proteine e qualità glutine |

De Vita et al., 2007; De Vita et al., 2010 |

|

Simeto |

Cultivar moderna, buona qualità semola/pasta; riferimento in studi su qualità tecnologica |

Troccoli et al., 2000; Ficco et al., 2014 |

In durum wheats, the association between glutenin allelic profile, protein composition, and technological quality is documented mainly through comparative studies on varietal collections and reference cultivars such as Creso and Simeto. This allows these cultivars to be used as scientific benchmarks, not merely as commercial names.

Important note on gluten quality in durum wheat:

For durum wheat, superior technological quality is not always defined by the same “strength” parameters used for bread (W, alveograph); often the focus is on viscoelasticity, tenacity, extensibility, and ability to form semolina/pasta. Nevertheless, the presence of certain HMW-GS combinations (also in tetraploids) has been documented and correlated with grain quality (total proteins, glutenin content, etc.). (Springer Nature Link)

What these examples tell us

✅ In soft wheats, certain HMW-GS profiles combined with specific subunits (e.g., 5+10 and Glu-B1 variants) are scientifically associated with better gluten quality parameters (and thus higher genetic potential). (MDPI)

✅ Some genotypes (such as GW-273 and GW-322) show very high quality scores, used as reference examples in technical publications. (Tandfonline)

✅ In durum wheats, the literature often includes lists of cultivars/lines with glutenin allelic profiles, useful for breeding and for correlating genetic profiles with quality (even if data are not always reported with standardized “commercial” names). (Springer Nature Link)