Riassunto

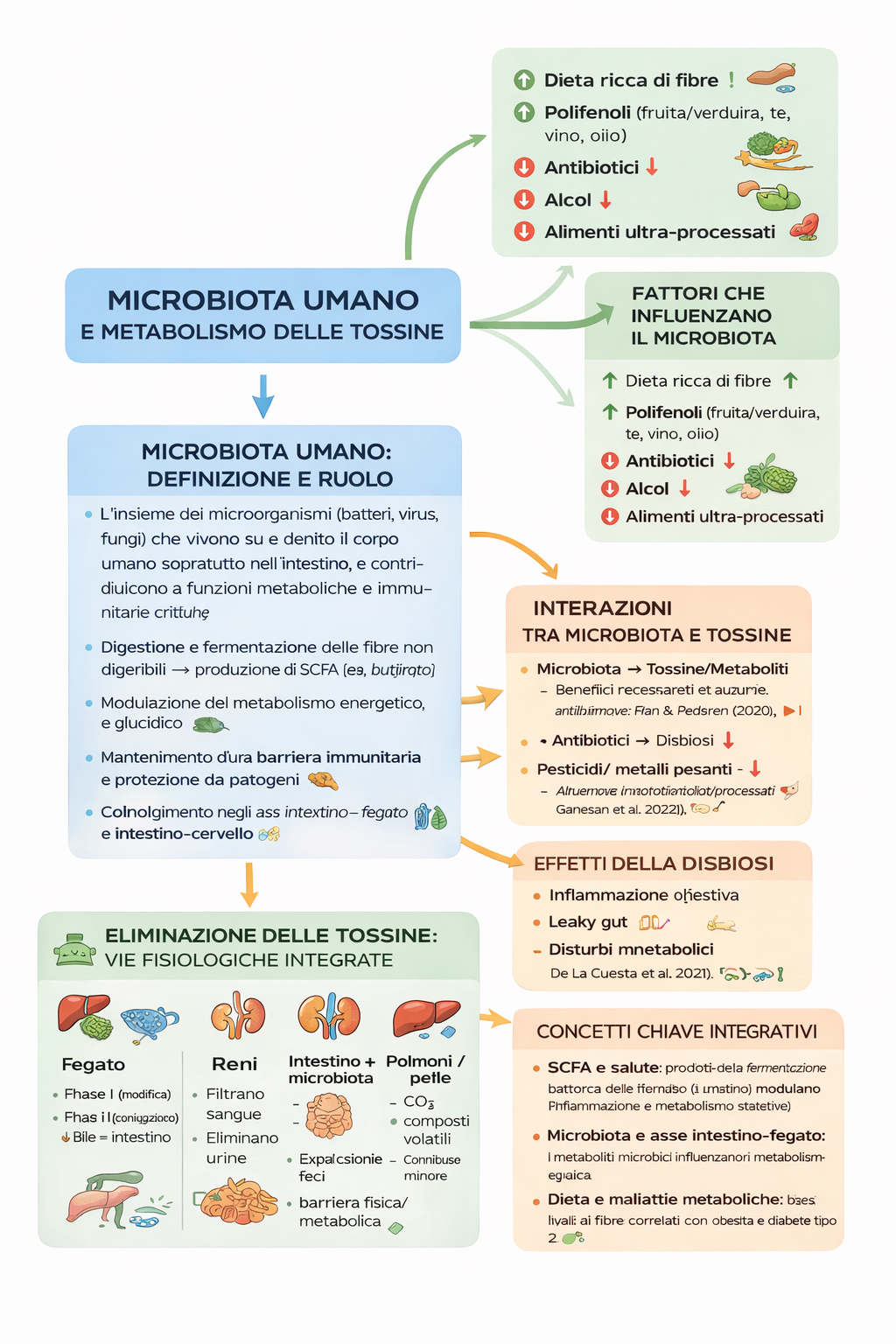

Il microbiota intestinale umano è un ecosistema complesso di microrganismi che svolge un ruolo centrale nella digestione, nella funzione immunitaria, nella regolazione metabolica e nella gestione delle tossine di origine alimentare e ambientale. Attraverso la fermentazione di fibre alimentari e carboidrati non digeribili, i batteri intestinali producono acidi grassi a catena corta (SCFA), come butirrato, acetato e propionato, che rappresentano un importante punto di comunicazione metabolica tra microbiota e organismo umano. Questi metaboliti fungono da substrati energetici per le cellule intestinali, contribuiscono al mantenimento della barriera intestinale e modulano i processi infiammatori e il metabolismo sistemico.

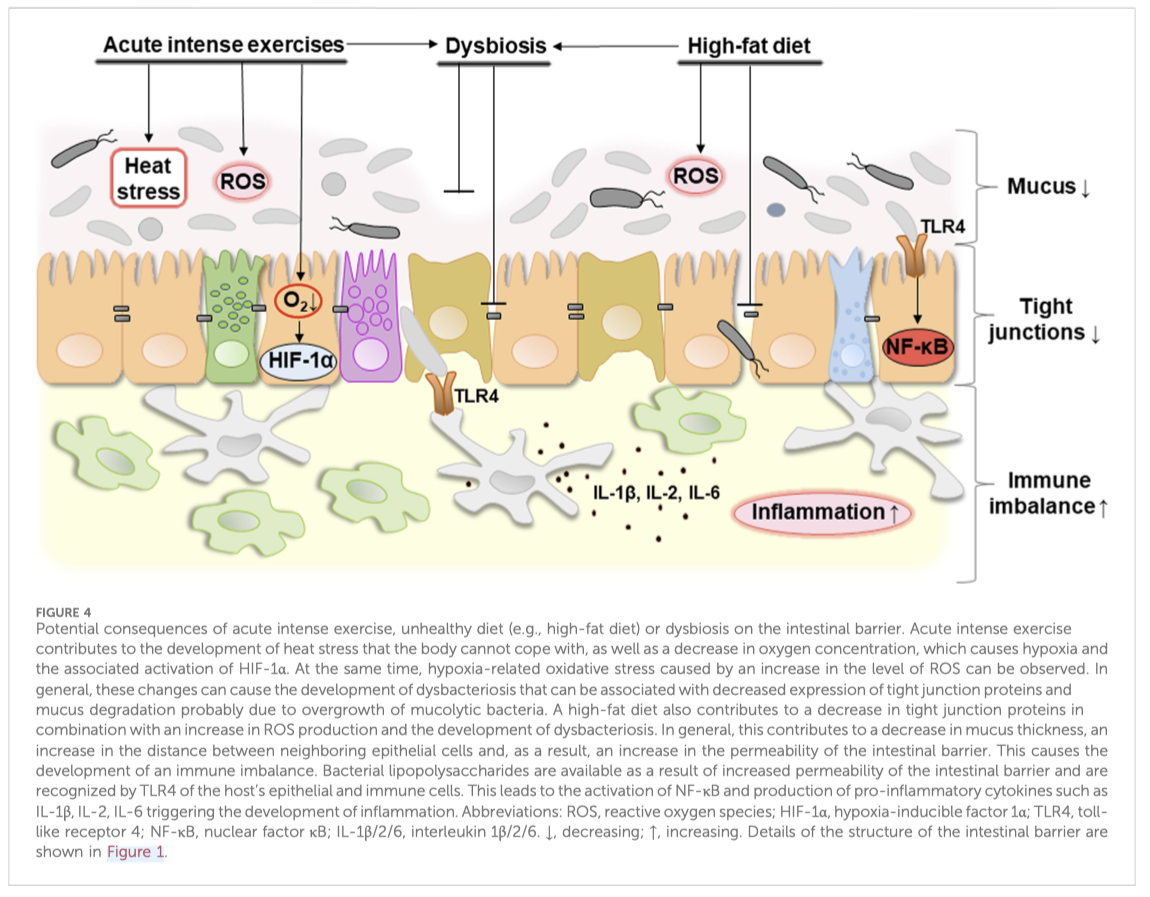

Il microbiota intestinale è inoltre coinvolto nella biotrasformazione degli xenobiotici, inclusi farmaci, additivi e inquinanti ambientali, influenzandone biodisponibilità e potenziale tossicità. Allo stesso tempo, fattori come antibiotici, sostanze inquinanti, alcol e alimenti ultra-processati possono alterare l’equilibrio microbico, favorendo disbiosi, aumento della permeabilità intestinale, infiammazione cronica e disturbi metabolici.

Questo articolo analizza le interazioni bidirezionali tra microbiota e tossine, i diversi tipi di fermentazione batterica (saccarolitica e proteolitica) e il concetto di simbiosi energetica tra microrganismi intestinali e ospite umano, evidenziando il ruolo fondamentale della dieta — in particolare dell’apporto di fibre — nel mantenimento della salute intestinale e metabolica.

Parole chiave:

Microbiota intestinale; Acidi grassi a catena corta (SCFA); Fibre alimentari; Butirrato; Fermentazione intestinale; Salute metabolica; Infiammazione; Barriera intestinale; Disbiosi; Metabolismo delle tossine; Asse intestino–fegato; Simbiosi energetica

1) Microbiota umano: definizione e ruolo

Definizione:

L’insieme dei microrganismi (batteri, virus, funghi) che vivono su e dentro il corpo umano, soprattutto nell’intestino, e contribuiscono a funzioni metaboliche e immunitarie critiche. (Nature)

Funzioni principali:

Digestione e fermentazione delle fibre non digeribili → produzione di SCFA (es. butirrato). (MDPI)

Modulazione del metabolismo energetico e glucidico. (Nature)

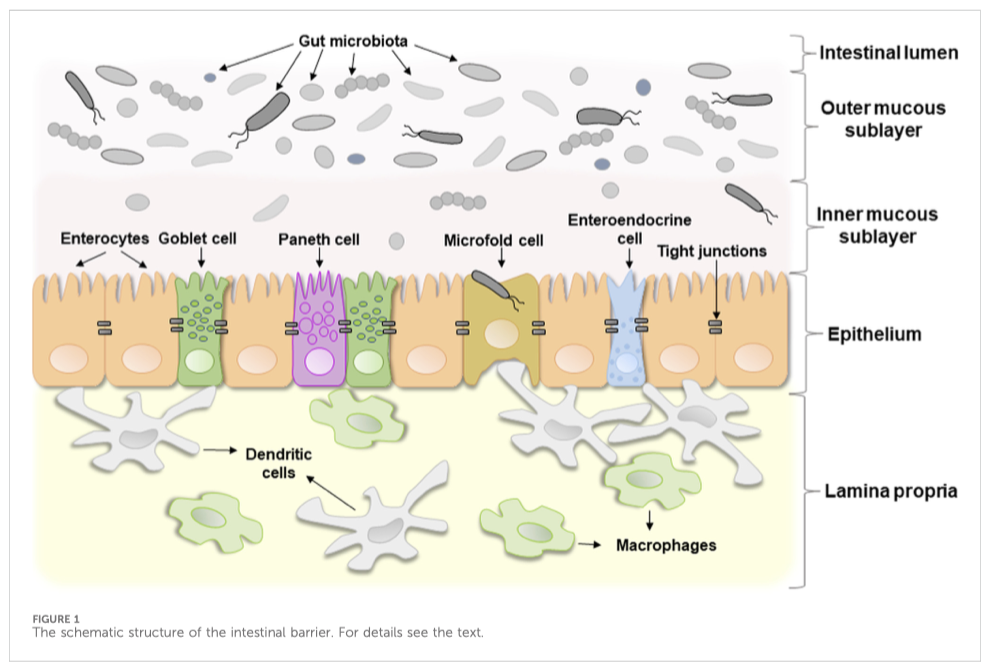

Mantenimento di una barriera immunitaria e protezione da patogeni. (Nature)

Coinvolgimento negli assi intestino-fegato e intestino-cervello. (attidellaaccademialancisiana.it)

2) Interazioni tra microbiota e tossine

2A – Microbiota → tossine/metaboliti

Il microbiota:

Fermenta le fibre [1] producendo metaboliti (SCFA) benefici. (MDPI)

Metabolizza xenobiotici (tossine ambientali, farmaci, additivi) influenzando la loro forma e tossicità. (MDPI)

Contribuisce alla barriera intestinale, limitando l’assorbimento di sostanze dannose. (attidellaaccademialancisiana.it)

Ricerche recenti:

1. Fan & Pedersen (2020): collegano microbiota e metabolismo dei composti derivati da alimenti e tossine negli esseri umani. (Nature)

2. Tu et al. (2020): revisione su microbioma e tossicità ambientale* (concetto di gut microbiome toxicity). (MDPI)

2B – Tossine → microbiota

Alcuni agenti impattano negativamente il microbiota:

Antibiotici → disbiosi intestinale

Pesticidi/metalli pesanti → alterano la diversità microbica

Alcol e alimenti ultra-processati → effetti negativi emergenti

Esempi di evidenze:

Ambientali e alimentari possono alterare l’equilibrio microbico e aumentare l’infiammazione. (ScienceDirect)

2C – Effetti della disbiosi

Una disbiosi (squilibrio del microbiota) può portare a:

Infiammazione intestinale

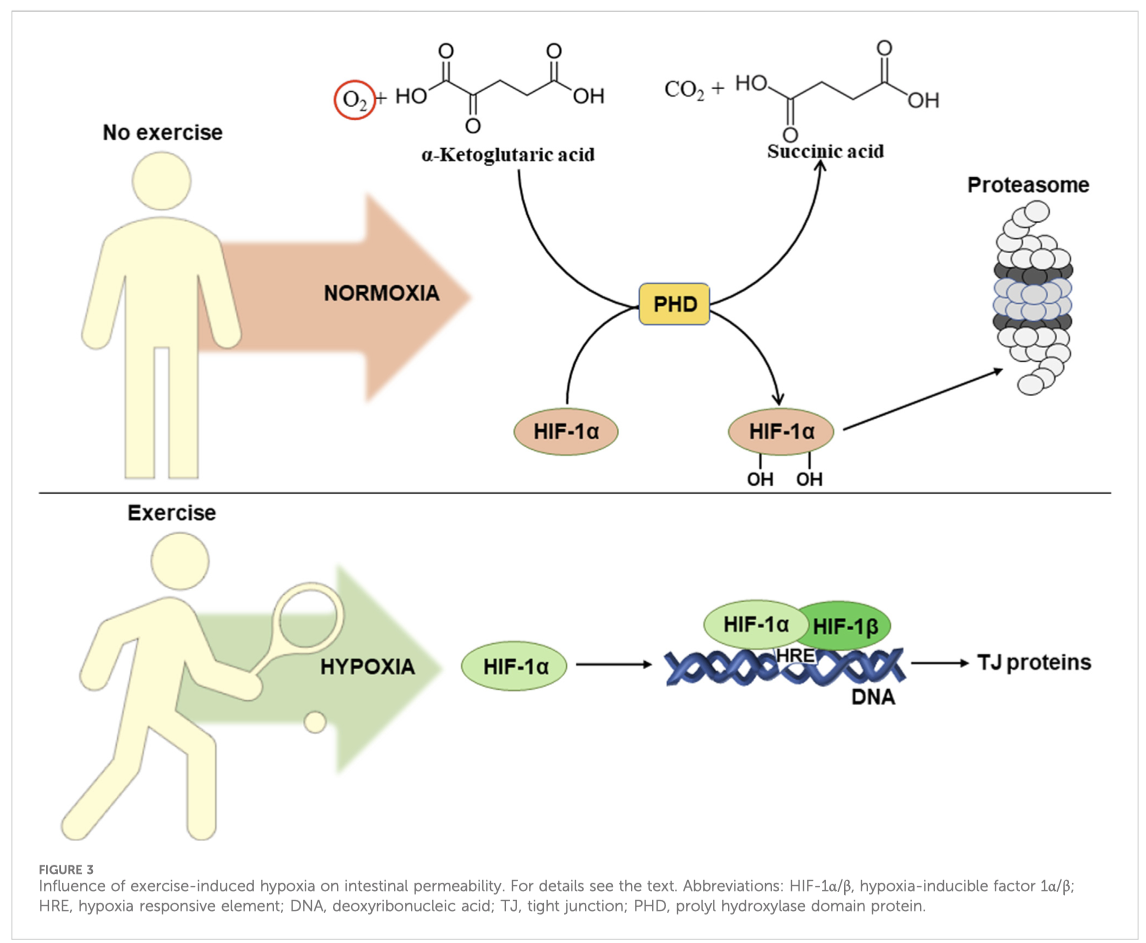

Aumento della permeabilità intestinale (leaky gut)

Disturbi metabolici (obesità, insulino-resistenza)

Evidenze scientifiche recenti:

Rassegna su metabolismo e salute umana collegati al microbiota. (Nature)

3) Fattori che influenzano il microbiota

Fattore

Effetto

Dieta ricca di fibre

↑ diversità e produzione SCFA (MDPI)

Polifenoli (frutta/verdura, tè, vino, olio)

modulano positivamente comunità microbica

Antibiotici

↓ biodiversità, ↑ disbiosi

Alcol

può danneggiare mucosa e favorire permeabilità

Alimenti ultra-processati

correlati a disbiosi (meccanismi ancora in studio)

Ricerche chiave:

1. Charnock & Telle-Hansen (2020): effetti delle fibre sul microbiota e sulla salute metabolica. (MDPI)

2. PubMed review (2023–2024): fibre e modulazione microbiota con implicazioni cliniche nelle malattie metaboliche. (PubMed)

4) Eliminazione delle tossine: vie fisiologiche integrate

Sistema epatico

Fase I: modifica strutturale delle tossine (ossidazione)

Fase II: coniugazione → più solubile

Eliminazione tramite bile → intestino

Il microbiota può modificare questi metaboliti e influenzare la loro recircolazione.

Reni

Filtrano il sangue

Eliminano tossine idrosolubili con urina

Intestino + microbiota

Espulsione delle tossine nei bocciamenti

Barriera fisica e metabolica contro l’assorbimento di composti dannosi

Polmoni e pelle

Eliminazione di CO₂ e composti volatili

Ruolo minore nella detossificazione di molecole più complesse

5) Concetti chiave integrativi

SCFA e salute

I prodotti della fermentazione batterica delle fibre (es. butirrato) non solo forniscono energia alle cellule intestinali ma modulano infiammazione e metabolismo sistemici. (MDPI)

Microbiota e asse intestino-fegato

I metaboliti microbici influenzano il metabolismo epatico, con potenziali effetti sulla gestione di tossine e grassi. (Nature)

Dieta e malattie metaboliche

Cambiamenti nel microbiota correlati a bassi livelli di fibra sono associati a obesità e diabete di tipo 2. (PubMed)

Mini-riassunto

1. Il microbiota intestinale è un ecosistema di microrganismi che supporta digestione, immunità e metabolismo; la sua alterazione (disbiosi) è collegata a malattie metaboliche. (Nature)

2. Le fibre alimentari non digeribili vengono fermentate dai microbi intestinali in composti benefici (SCFA). (MDPI)

3. Microbiota e tossine si influenzano reciprocamente: il microbiota può degradare o trasformare composti estranei, mentre sostanze come antibiotici e inquinanti possono alterare la flora. (MDPI)

4. L’organismo elimina tossine tramite fegato, reni, intestino (coinvolgendo microbiota), polmoni e pelle.