Il sistema immunitario

Il sistema immunitario (innato ed adattivo) è l’unica arma che il corpo ha per combattere il nuovo coronavirus covid-19. Ad oggi non ci sono cure o vaccini in grado di debellarlo. L’analisi delle modalità con cui il virus infetta ha ampiamente dimostrato che la sua letalità è strettamente correlata con la salute dell’individuo: più patologie sono presenti più il virus è letale. La popolazione colpita dal virus in modo grave presenta un’età piuttosto avanzata in concomitanza con una salute più fragile. Il virus infetta anche persone più giovani che reagiscono in modo più efficace all’infezione a meno di non avere patologie pregresse importanti. E’, dunque, essenziale che il sistema immunitario di ogni persona sia al massimo dell’efficienza in modo da poter fronteggiare il virus con la massima efficacia. Lo stress e l’alimentazione giocano un ruolo di primo piano nel conservare in buone condizioni il sistema immunitario e, se i tempi che viviamo non ci aiutano a certo a diminuire lo stress, l’alimentazione può essere più facilmente adattata per meglio mantenerci in salute.

Importanza dell’alimentazione

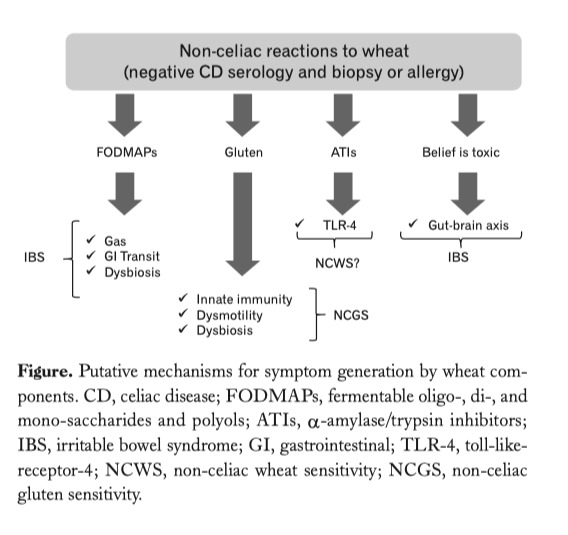

Su questo tema la medicina è piena di utili consigli ma va richiamato in modo particolare il ruolo degli alimenti prodotti con farina di grano e/o farro perché sono presenti in maniera massiccia nella nostra dieta. E’ necessario evidenziare quanto frequenti siano le malattie e i disordini grastro-intestinali derivanti dal consumo di prodotti realizzati con grano. Tra cui: sensibilità al glutine non celiaca (NCGS – non celiac gluten sensivity) [1], la sensibilità al grano non celiaca (NCWS-non celiac wheat sensivity) [2], la sindrome dell’intestino irritabile (IBS) [3], glicemia, sensibilità alle ATI (amylase trypsina inibitors) [4]; sensibilità alle FODMAP’s (Fermentable Oligo-, Di- and Mono- saccharides And Polyols) [5]; infiammazione intestinale (IBD inflammatory bowel disease) [6]. Per ridurre l’incidenza di queste patologie, spesso debilitanti, la ricerca scientifica da molto tempo ha suggerito non solo di ridurre la quantità degli alimenti che causano una reazione avversa del sistema immunitario ma anche di introdurre nella dieta prodotti realizzati con grani ricchi di fibra vegetale più digeribili e più tollerabili [7]. La riduzione di questo tipo di alimenti, però, se portata all’eccesso con una rimozione totale può comportare lo sviluppo di una nuova reattività verso l’alimento sostitutivo, magari con gli stessi sintomi di prima. Un esempio è rappresentato dalla reattività al glutine; in questo caso spesso i medici consigliano il consumo di cibi “gluten-free” e la sostituzione del frumento utilizzato, per esempio, con il riso. La totale eliminazione del glutine provoca inoltre una sensibile disbiosi intestinale [8]. Alimenti assunti in eccesso possono provocare la reazione del sistema immunitario [9]. In molti casi, quindi, è sufficiente diluire l’assunzione di quell’alimento verso il quale il nostro sistema immunitario reagisce (studi di Cai, pubblicati nel 2014 su PLoS One). Va precisato che l”infiammazione da cibo dovuta al glutine non è da confondersi con la celiachia, o con l’allergia IgE-mediata al frumento.

Microbiota intestinale

“Il microbiota intestinale è uno degli elementi fondamentali di tutto l’ecosistema intestinale. Quest’ultimo, infatti, comprende tre componenti: la barriera intestinale, che è un filtro molto selettivo e importante per il benessere dell’intero organismo, una struttura di tipo neuroendocrino oggi chiamata comunemente secondo cervello e, infine, il microbiota intestinale che, pur non essendo un vero organo perché funzionalmente ci appartiene anche se non dal punto di vista anatomico, da sempre ci accompagna nell’evoluzione filogenetica (dott. Edoardo Felisi dell’Università di Pavia)”. E’ costituito prevalentemente da batteri, lieviti, parassiti e virus. La loro condizione di equilibrio è definita di eubiosi. Equilibrio che permette alle varie componenti del microbiota intestinale di svolgere in modo efficace una serie di funzioni essenziali: funzioni di tipo metabolico, quindi sintesi di sostanze utili all’organismo, di tipo enzimatico, di protezione e stimolo verso il sistema immunitario e di eliminazione di tossici. Funzioni da cui dipende la salute generale dell’organismo. Tra I principali componenti del microbiota troviamo le colonie batteriche: Firmicutes, Bacteroides, Proteobacteria e Actinobacteria. Firmicutes e Bacteroides rappresentano circa il 90% . La ricerca scientifica ha dimostrato come il variare del rapporto tra queste componenti faciliti e promuova uno stato di disbiosi che può comportare malattie dell’apparato digerente. Può inoltre avere un ruolo in malattie come il diabete, l’obesità, la dermatite, le patologie cardiovascolari, l’Alzheimer, il Parkinson ecc. Il microbiota varia con l’età e, soprattutto con l’alimentazione. Infezioni e farmaci (assunti in modo cronico) sono i fattori che incidono negativamente nella composizione del macrobiota cosi come le diete iperproteiche o con troppi carboidrati e stili di vita sbagliati (non fare attività fisica, fumo, l’abuso di alcool, ecc.) protratti nel tempo. La disbiosi, soprattutto cronica comporta anche importanti alterazioni funzionali che coinvolgono soprattutto la barriera intestinale. La barriera intestinale è formata da strutture chiamate “giunzioni serrate” o “thight junction” che mettono in collegamento le varie cellule intestinali e che permettono il passaggio bidirezionale di sostanze dal lume intestinale al torrente circolatorio. Sono strutture proteiche che traggono grande beneficio e sono molto condizionate nella loro funzionalità da sostanze come gli acidi grassi a catena corta, prodotti proprio dal metabolismo del microbiota intestinale. L’alterazione del microbiota intestinale, se protratta a lungo, comporta l’alterazione della funzionalità delle giunzioni serrate e quindi il passaggio di sostanze tossiche, di allergeni, di microbi nel sistema circolatorio e quindi dall’intestino a tutto l’organismo.