Danneggiamento dell’amido del grano

L’amido del grano è composto di due sostanze:

- L’amilopectina: è un polisaccaride a catena ramificata, può essere composto da circa 1 a 6000 molecole di glucosio. Tende a disporsi nella parte centrale dei granuli di amido e non è solubile in acqua. Generalmente rappresenta l’80% del totale.

- L’amilosio è invece un polisaccaride a catena lineare. Può arrivare a contenere fino a 600 molecole di glucosio. Tendenzialmente si aggira intorno al 20% del totale. Si scioglie alle alte temperature e in acqua.

Questi due costituenti vanno a determinare le differenze tra gli amidi, in funzione delle loro ramificazioni e del grado di polimerizzazione.

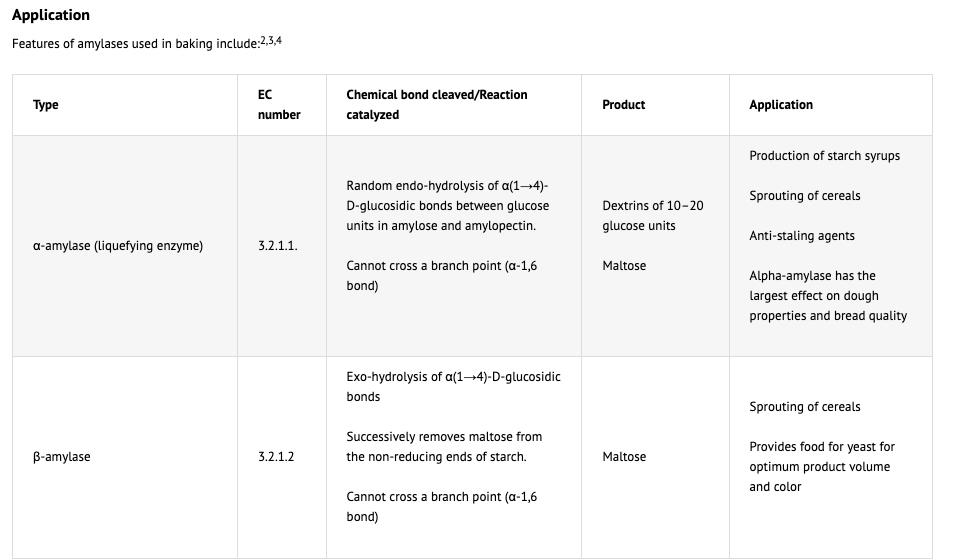

L’amido rappresenta il 67-68% del grano integrale e tra il 78-82% della farina prodotta dalla macinazione. La struttura semicristallina del granello di amido nel chicco di grano è danneggiata da operazioni meccaniche, in particolare dal processo di macinazione che lo frantuma. Il livello di danneggiamento dell’amido influenza direttamente l’assorbimento d’acqua e le proprietà di miscelazione dell’impasto ed ha, quindi, una grande importanza tecnologica. L’amido danneggiato assorbe da 2 a 4 volte più acqua rispetto ai normali granuli di amido. I granuli di amido frantumati sono oggetto dell’azione delle alfa e beta amilasi (1); le prime trasformano l’amido in maltosio e destrine (2) e le seconde lo trasformano in maltosio. Un valore eccessivo di amido danneggiato comporta un elevato assorbimento d’acqua, impasti appiccicosi, tempi di lievitazione più lunghi e colore scuro della crosta. Una migliore conoscenza dei livelli di amido danneggiato nelle farine è essenziale per un loro migliore utilizzo. Il valore ottimale di amido danneggiato varia con l’uso della farina ed è fortemente dipendente dal contenuto proteico della farina, dall’attività alfa-amilasi e dal tipo di pane che si desidera. L’amido è un polimero del glucosio e si presenta in due diverse forme: amilosio e amilopectina.

L’amilosio è una catena lineare avvolta a elica, in cui le unità sono legate tra loro con legami glucosidici α(1→4). L’amilopectina è costituita da una catena di base formata da unità di glucosio legate α(1→4), da cui partono ramificazioni laterali legate α(1→6). L’azione della alfa-amilasi sull’amido può essere ostacolata anche dalla presenza di polisaccaridi non digeribili, le fibre: cellulosa, emicellulosa e pectina. Le catene di amilosio, e in misura minore le ramificazioni dell’amilopectina, grazie alla formazione di legami a idrogeno con molecole vicine e all’interno delle molecole stesse, hanno la tendenza ad aggregarsi. Per questo motivo amilosio ed amilopectina puri risultano scarsamente solubili in acqua al di sotto dei 55°C, e più resistenti alla digestione enzimatica (amido resistente), ossia difficilmente attaccabili dalla alfa-amilasi. Va comunque notato che i granuli posti in soluzione acquosa s’idratano, con un conseguente aumento di volume di circa il 10%. Al di sopra dei 55 °C la struttura parzialmente cristallina viene persa, i granuli assorbono ulteriore acqua, si gonfiano e si passa ad una struttura disorganizzata, ossia si verifica la gelatinizzazione con cui l’amido assume una struttura amorfa più facilmente attaccabile dalla α-amilasi.

In sintesi, le amilasi svolgono le seguenti funzioni nei prodotti da forno:

- Fornire zuccheri fermentabili e riducenti.

- Accelerare la fermentazione del lievito e aumentare la gassificazione per un’espansione ottimale dell’impasto durante la lievitazione e la cottura

- Intensificare i sapori e il colore della crosta migliorando le reazioni di doratura e caramellizzazione di Maillard.

- Ridurre la viscosità dell’impasto / pastella durante la gelatinizzazione dell’amido nel forno.

- Estendere l’aumento di volume della pagnotta appena viene messa nel forno. dovuto al forte calore.

- Ammorbidire la mollica inibendo il raffermamento (staling).

- Modificare le proprietà di manipolazione dell’impasto riducendo la viscosità.

Note

(1) “Two amylases are common to the baking industry, α-amylase and β-amylase also known as α-1,4-glucan glucanohydrolase and α-1,4-glucan maltohydrolase. Amylases convert starch into sugar: the α-amylase will cleave the starch randomly (the so called 1-4 bonds in the starch) while the β-amylase can only chop off two sugar units at the time at the end of the starch chain. Normally there is enough β-amylase present in the flour but sometimes addition of α-amylase is needed. The α-amylase will cut the starch into smaller units called dextrins and the more α-amylase activity there is, the better for the β-amylase because there are more extremities available. So the substrate for the β-amylase is either starch or dextrins and the product is maltose. α-amylase is an endo-enzyme that attacks linkages within the molecular structure. It randomly cleaves starch chains at interior a-1,4-glycosidic linkages producing short chains of glucose molecules or dextrins. β-amylase is an exo-enzyme and cleaves maltose units from the non-reducing end of the starch molecule. In order for these enzymes to function, the starch granule must be ruptured so that the individual starch molecules are available for enzymatic action. Depending upon their origin, α- and β-amylases show differences in pH and temperature optima, thermostability, and other chemical stability. They do not require coenzymes for activity, although α-amylase activity is enhanced by the presence of calcium. This pH dependence decreases the efficacy of this enzyme in sourdoughs. β-Amylase is active across a much broader pH range, 4.5-9.2, with a pH optimum of 5.3. α-Amylase is relatively thermostable up to 70°C, whereas β-amylase loses about half of its activity at this temperature. Fungal amylase is the least temperature stable, followed by cereal amylase, while bacterial amylase is stable at higher temperatures. New intermediate stability enzymes have been developed that are active above the gelatinisation temperature of starch (60°C), but are totally inactivated at the later stages of baking (80-90°C). The objective is to maximize the anti-staling effect without creating a gummy, sticky product. Bakery technology – Enzymes http://www.classofoods.com/page1_7.html “

(2) “Amylase activity also leads to dextrins, which have an important effect on water-holding ability and porosity of the dough, as well as on bread softness, an excessive dextrin production is observed and sticky dough is obtained. The rheological properties of the dough are slightly modified by amylolytic consumption of damaged starch. Damaged starch has a large hydration capacity and its disappearance leads to a decreasing dough consistency. Consequently, although the production of oligosaccharides represents the positive aspect of amylolytic activity, the negative effect of damaged starch consumption on the rheological properties of dough should not be neglected. “ omissis “The more important factor in baking quality is the gluten characteristics of dough. Strong dough with an extensive gluten network is suitable for bread making [8]. In contrast, weak dough without an extensive gluten network is best for cookies and cakes [9]. For this reason the effect of damaged starch on flour quality is difficult to identify independently of protein influence, so we think that it is important to clarify damaged starch effects on baking quality limiting protein influence. “Influence of damaged starch on cookie and bread-making quality (vedi approfondimenti).

The temperature and pH optimum of α-amylase.

The temperature optimum of α-amylase was 40 – 50 °C in all sets of wheat (Figure 10a) and maize cultivars (Table 17). These values are comparable with that of cereal amylases (Mohamed et al. 2009; Al-Bar 2009; Nirmala and Muralikrishna 2003). …omissis…From technological point of view, enzyme’s temperature optimum considers an indicator for food processing application. In breadmaking, the temperature pattern during breadmaking process is divided into three stages (Drapron and Godon 1987): 1) dough- making, it includes mixing ingredients and fermentation. During this step the temperature does not exceed 25 °C. 2) Baking on the oven. Dough is subjected to a constantly increasing temperature from 25 °C up to a maximum of 100 °C. 3) Cooling and storage loaves, the bread is cooled to 25 °C. It is a common practice in breadmaking to use α-amylase from different sources as supplementation in flour to yiled fermentable sugars (Goesaert et al. 2005). Rosell et al. (2001) compared the temperature optimum of α-amylase from different origins (wheat, malted barley, fungi and bacteria) in order to optimize the use of α-amylase in flour standardization. They found that it is very difficult to satisfactorily control the level of bacterial α-amylase in bread making, because of its ability to survive at high temperatures found in the baking stage. On the other hand, cereal and fungal α-amylases had a different behavior. Fungal α-amylase is the most thermo labile, followed by those from cereal. …..omissis……The pH range of the maximal activity of α-amylase was within 4 and 6 in both wheat (Figure 10b) and maize (Table 17 and Figure 14b). Similar results have been reported for α- amylase from wheat (Mohamed et al. 2009), maize, sorghum, (Egwim and Oloyede 2006) and barley (Al-Bar 2009). From food technological point of view, the pH in most of food applications can not be readily adjusted to the pH optimum of α-amylase. Therefore, the origin of enzyme has to be chosen on the basis of its activity at the natural food pH (Curvelo et al. 2008; Cato 2005). For instance, natural pH of starch surry is general around 4.5 (Sivaramakrish 2006). Egwim and Oloyede (2006) tested the suitability of α-amylase from different sprouting Nigerian cereals (maize, acha, rice and sorghum) in starch hydrolysis processes based on the pH value. They found that the four cereals exhibited broad pH optima of α- amylase, ranging from 4 to 6, which was in agreement with the industrial practice. ……omissis….Sometimes the activity of α-amylase that presents naturally in flour is not suffient to produce good bread volume and quality. Therefore, flour is routinely supplemented with exogenous amylases to optimize the amylase activity. Commercial amylase can be obtained from fungal, cereal or bacterial sources (Goesaert et al. 2005). Studies carried out by Rosell et al. (2001) have tested the activity of amylase from those commercial sources with the process condition in breadmaking. They found that the pH optimum of cereal α-amylase at 4.5 – 6.0 was appropriate to use this source of enzyme in flour standardization. We may suggest using them as source of amylases in flour standardization for breadmaking owing to the broad optimum pH of their amylases. Characterization of α-amylase in wheat and maize. Dissertation

to obtain the Ph. D. degree

in the International Ph. D. Program for Agricultural Sciences in Göttingen (IPAG)

at the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Georg-August-University Göttingen, Germany presented by Hanadi Riyad Aljabi born in Damascus, Syria Göttingen, May 2014.”

Approfondimenti:

1 – Bakery technology – Enzymes

2 – Influence of damaged starch on cookie and bread-making quality.

3 – INFLUENCE OF AMYLASES ON THE RHEOLOGICAL PROPERTIES OF WHEAT FLOUR WITH PARTIALLY DAMAGED STARCH.

4 – The Effect Of Damaged Starch On The Quality Of Baked Good.

Back