Uno studio molto importante che evidenzia la sovrapposizione dei sintomi della sindrome dell’intestino irritabile con quelli generati dalla sensibilità al glutine non celiaca dalle ATI e da Fodmaps.

“A tight link exists between dietary factors and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), one of the most common functional syndromes, characterized by abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating and alternating bowel habits. Amongst the variety of foods potentially evoking “food sensitivity”, gluten and other wheat proteins including amylase trypsin inhibitors represent the culprits that recently have drawn the attention of the scientific community. Therefore, a newly emerging condition termed non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) or nonceliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS) is now well established in the clinical practice. Notably, patients with NCGS/NCWS have symptoms that mimic those present in IBS. The mechanisms by which gluten or other wheat proteins trigger symptoms are poorly understood and the lack of specific biomarkers hampers diagnosis of this condition. The present review aimed at providing an update to physicians and scientists regarding the following main topics: the experimental and clinical evidence on the role of gluten/wheat in IBS; how to diagnose patients with functional symptoms attributable to gluten/wheat sensitivity; the importance of double-blind placebo controlled cross-over trials as confirmatory assays of gluten/wheat sensitivity; and finally, dietary measures for gluten/wheat sensitive patients. The analysis of current evidence proposes that gluten/wheat sensitivity can indeed represent a subset of the broad spectrum of patients with a clinical presentation of IBS. (J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;22:547-557). Umberto Volta, Maria Ines Pinto-Sanchez et al.

Extrac from the study:

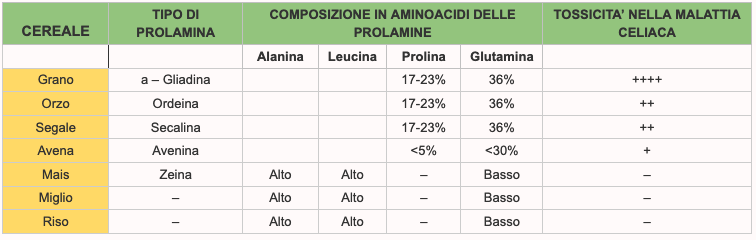

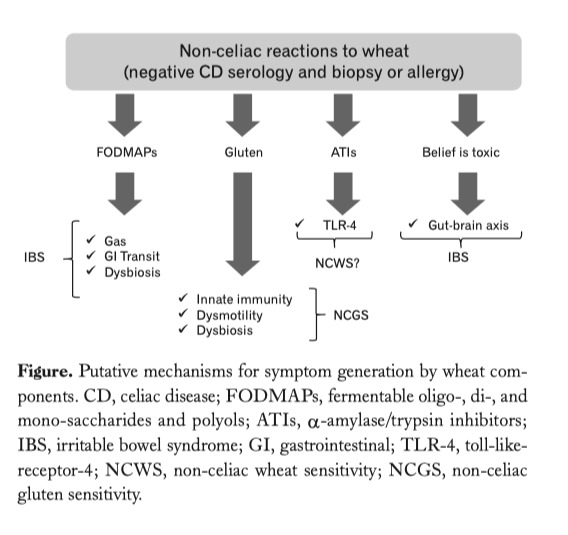

…..omissis. Experimental Evidence for a Role of Wheat Components in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Different mechanisms have been proposed to explain how gluten may trigger gastrointestinal symptoms in the absence of celiac disease (Figure).

In vitro studies have demonstrated that digests of gliadin increase the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and the production of proinflammatory cytokines in monocytes and dendritic cells (40,57,58). Certain “toxic” (that only stimulates the innate immune response) gliadin-derived peptides such as the 31-43mer, may evoke epithelial cell dysfunction, increased IL-15 production and enterocyte apoptosis (59). Recent studies have demonstrated increased expression of TLR-2 in the intestinal mucosa of non-celiac compared to celiac patients, suggesting a role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of non-celiac reactions to gluten or other wheat components (49). Other studies have shown that monocytes from HLA-DQ2+ non-celiac individuals spontaneously release 2-3 fold more IL-8 than monocytes from HLA-DQ2 negative patients. This suggests that patients without celiac disease (no enteropathy and negative specific serology), but with positive HLA-DQ2 status, may represent a subpopulation reacting mildly to gluten (60). In terms of gut dysfunction, gluten sensitization in mice has been shown to induce acetylcholine release, one of the main excitatory neurotransmitters in the gut, from the myenteric plexus (57).

In vitro studies have demonstrated that digests of gliadin increase the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and the production of proinflammatory cytokines in monocytes and dendritic cells (40,57,58). Certain “toxic” (that only stimulates the innate immune response) gliadin-derived peptides such as the 31-43mer, may evoke epithelial cell dysfunction, increased IL-15 production and enterocyte apoptosis (59). Recent studies have demonstrated increased expression of TLR-2 in the intestinal mucosa of non-celiac compared to celiac patients, suggesting a role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of non-celiac reactions to gluten or other wheat components (49). Other studies have shown that monocytes from HLA-DQ2+ non-celiac individuals spontaneously release 2-3 fold more IL-8 than monocytes from HLA-DQ2 negative patients. This suggests that patients without celiac disease (no enteropathy and negative specific serology), but with positive HLA-DQ2 status, may represent a subpopulation reacting mildly to gluten (60). In terms of gut dysfunction, gluten sensitization in mice has been shown to induce acetylcholine release, one of the main excitatory neurotransmitters in the gut, from the myenteric plexus (57).

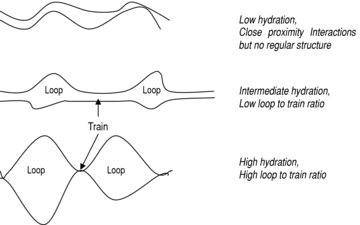

This correlates with increased smooth muscle contractility and a hypersecretory status with increased ion transport and water movements (57). These functional effects induced by gluten were not accompanied by mucosal atrophy, and were not observed after sensitization with non-gluten proteins. Interestingly gluten-induced gut dysfunction was particularly notable in mice transgenic for the human celiac gene HLA-DQ8 (57).

ATIs, a group of wheat proteins that confer resistance of the grain to pests, are strong inducers of innate immune responses via TLR4 and via the myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent and -independent pathway (40). This activation occurs both in vitro and in vivo after oral ingestion of purified ATIs or gluten, while gluten-free cereals display no or minimal activities (61). The role of ATIs in IBS is not yet known, however there is clear description of a mechanism that could be involved in the generation of gut dysfunction and symptoms. These mechanisms are different from those proposed for gluten and thus it is conceivable that they could co-exist in given patients or have a synergistic effect.