In evidenza alcune risultanze della ricerca Leaky Gut, Leaky Brain? Mark E. M. Obrenovich 2018 MDPI:

Omissis……

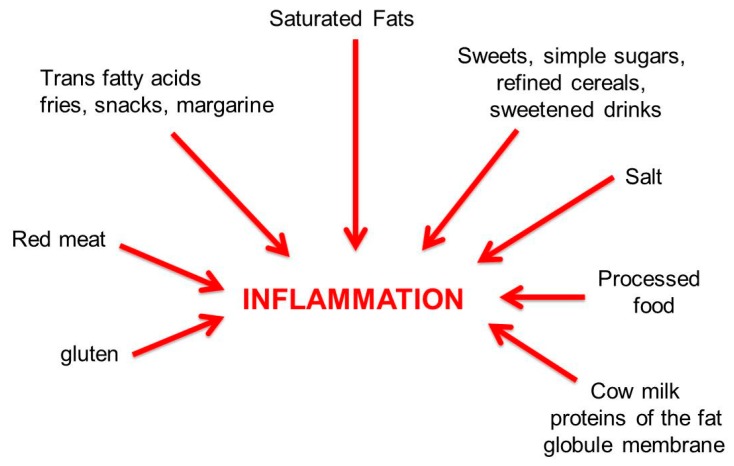

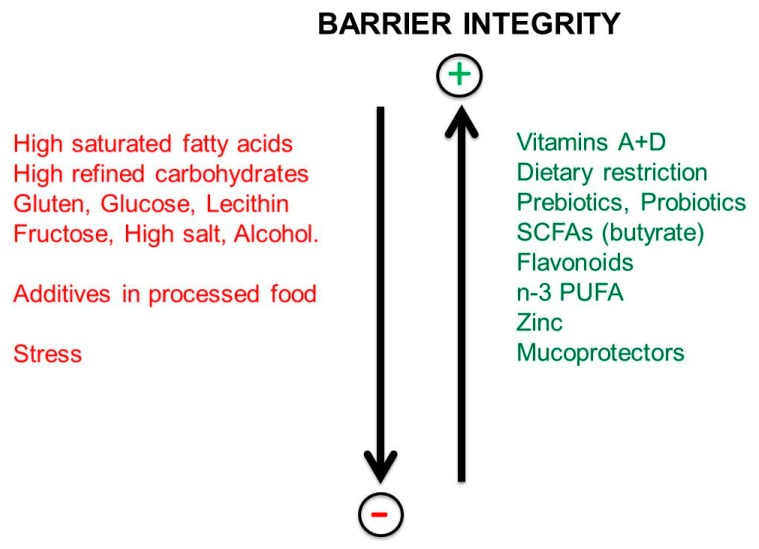

“Il modo in cui le proteine e i peptidi della gliadina resistenti alla digestione (A-gliadina P31–43) possono indurre una risposta allo stress o innescare risposte immunitarie innate può essere uno dei meccanismi nella perdita di tolleranza al glutine [32]. È stato dimostrato che la risposta immunitaria innata aumenta la zonulina, che è un modulatore delle giunzioni strette intercellulari e del traffico di macromolecole importanti nella tolleranza e nelle risposte immunitarie. La disregolazione della via della zonulina può aumentare la permeabilità delle giunzioni strette (epitelio intestinale) e [33]. L’invecchiamento può anche influenzare le barriere di permeabilità poiché è stato riscontrato che le risposte immunitarie innate aumentano nelle scimmie anziane in linea con carichi di traslocazione microbica più elevati, ma i profili del microbioma dell’RNA 16S non hanno mostrato grandi differenze in base all’età. I meccanismi dietetici ricavati da studi sulle scimmie dimostrano disfunzione della barriera gastrointestinale e permeabilità intestinale correlata all’età e risposte alterate a una dieta occidentale, senza malattia celiaca.”

Omissis…..

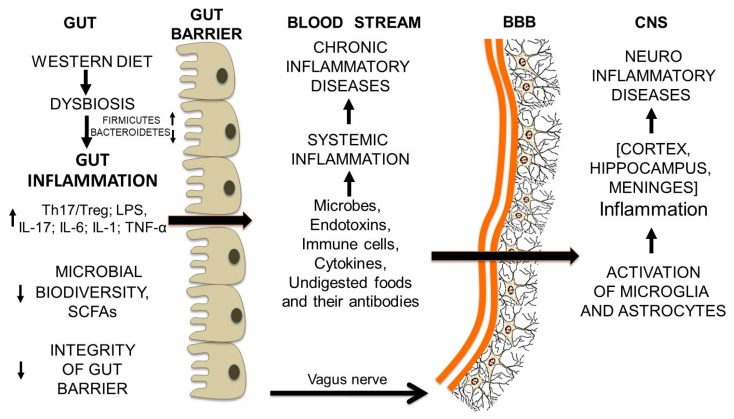

“La permeabilità intestinale può essere una delle cause (da sottolineare) delle malattie concomitanti che coinvolgono interruzioni nella barriera ematoencefalica [4,6,10,13,15,16,29] e numerosi studi indicano che l’ipossia e/o l’infiammazione aumentano la permeabilità paracellulare della BEE (barriera ematoencefalica)[12].”

Omissis…..

“Insieme alle proteine di trasporto selettive, le barriere consentono ai nutrienti, all’ossigeno, agli aminoacidi, ad alcuni farmaci e al glucosio di entrare nel liquido cerebrospinale e impediscono alle molecole idrofobiche di passare nelle interfacce delle barriere sangue-fluido cerebrospinale, vale a dire nel liquido cerebrospinale e nel plesso coroideo.”

Omissis…..

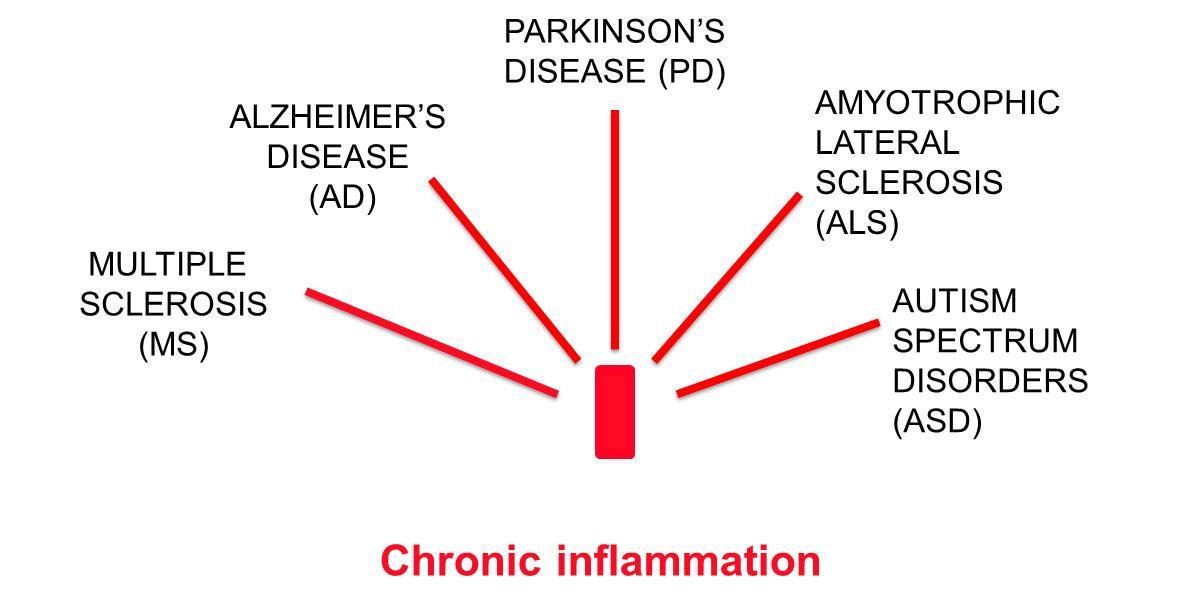

“L’infiammazione interrompe la BBB: The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a selective semi-permeable membrane between the blood and the interstitium of the brain, allowing cerebral blood vessels to regulate molecule and ion movement between the blood and the brain.). Molte malattie e fattori di stress fisiologici che colpiscono il sistema nervoso centrale alterano anche l’integrità funzionale della BEE = BBB (barriera ematoencefalica)[15,16]. Influiscono sulla capacità della barriera di limitare selettivamente il passaggio di sostanze dal sangue al cervello. In aggiunta a ciò, l’ipossia e/o l’infiammazione e il processo infiammatorio alterano le proprietà di permeabilità e contribuiscono alla patofisiologia delle malattie del sistema nervoso centrale, portando ad un rilascio alterato di agenti terapeutici al cervello [10].”

Riassumendo (dall’intestino al cervello):

peptidi della gliadina possono innescare la risposta del sistema immunitario innato

la risposta immunitaria innata aumenta la zonulina

la disregolazione della via della zonulina può aumentare la permeabilità delle giunzioni strette (epitelio intestinale) e rendere gli individui suscettibili a possibili disturbi autoimmuni, cancro e infiammazione

la permeabilità intestinale può essere una delle cause (da sottolineare) delle malattie concomitanti che coinvolgono interruzioni nella barriera ematoencefalica

Note

Le barriere più importanti sono la barriera ematoencefalica (BEE), la barriera emato-gastrointestinale (GBB), le barriere emato-oculari e emato-retiniche, le barriere emato-placentarie e emato-testicoli, la barriera emato-timica e la barriera emato-polmonare o delle vie aeree. Ognuna di queste barriere protegge organi e sistemi vulnerabili e sensibili.

La barriera emato-encefalica (BEE) è una unità anatomico-funzionale realizzata dalle particolari caratteristiche delle cellule endoteliali che compongono i vasi del sistema nervoso centrale e ha principalmente una funzione di protezione del tessuto cerebrale dagli elementi nocivi presenti nel sangue, pur tuttavia permettendo il passaggio di sostanze necessarie alle funzioni metaboliche ed al sistema enterocettivo

Nell’intestino, la barriera tra il corpo e l’ambiente luminale è formata dalla mucosa gastrointestinale, che tampona nutrienti, microrganismi e tossine. Le barriere sono semipermeabili, consentendo così un trasporto efficiente dei nutrienti attraverso l’epitelio, escludendo l’ingresso di piccole molecole e organismi potenzialmente dannosi. Le proprietà esclusive della mucosa gastrica e intestinale sono indicate come barriera sanguigna gastrointestinale [20].

La mucosa intestinale è lo strato più interno della parete intestinale. È formata dai villi intestinali che aumentano la superficie di assorbimento dei nutrienti. Come tale, si affaccia direttamente sul lume dell’intestino, a stretto contatto con i prodotti della digestione. Al di sotto della mucosa, procedendo verso l’esterno, si incontrano le rimanenti tuniche: la sottomucosa, la muscolare e la sierosa.

Approfondimento

Titolo originale dell’articolo: A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science; 1 novembre 2015

“Può sembrare incredibile che ancora oggi si scoprano nell’uomo nuove strutture anatomiche e invece è proprio così. Recentissima, per esempio, è la scoperta, pubblicata sulla rivista Science, di una barriera vascolare-intestinale in grado di impedire ai batteri dell’intestino di passare nel circolo sanguigno. L’ha individuata un’équipe guidata da Maria Rescigno, direttrice del Programma di immunoterapia all’Istituto europeo di oncologia di Milano, che svolge la sua attività di ricerca con il contributo fondamentale di AIRC.

“Sapevamo che, almeno in individui sani, i batteri intestinali rimangono confinati in quest’organo, però volevamo anche capire che cosa ne impedisca la disseminazione” spiega Rescigno. Con esperimenti condotti nei topi, i ricercatori hanno scoperto una nuova struttura vascolare al di sotto dell’epitelio, il tessuto di rivestimento dell’intestino. “È una barriera fatta principalmente di cellule endoteliali- le cellule che rivestono l’interno dei vasi sanguigni – molto vicine le une alle altre, in modo da consentire il passaggio dall’intestino alla circolazione sanguigna delle sostanze nutritive, ma non dei batteri”. I dati raccolti permettono di dire che una barriera analoga è presente anche nell’uomo.

Se la barriera è alterata – e i ricercatori hanno già individuato marcatori in grado di segnalarlo – alcuni batteri possono spostarsi dall’intestino al fegato, creando un’infiammazione che a lungo andare può provocare danni epatici. “Pensiamo sia quello che accade in pazienti con diabete di tipo 2 o in pazienti celiaci che, pur seguendo una dieta senza glutine, mostrano segni di danno epatico” sottolinea la studiosa.

Ora l’idea è capire se ci sono tipi di microbiota (l’insieme della popolazione di batteri in un determinato organo) più o meno protettivi nei confronti della barriera e scoprire i dettagli molecolari degli eventi coinvolti. Altre applicazioni della scoperta potrebbero riguardare l’ambito oncologico. “Stiamo lavorando per capire meglio il coinvolgimento della barriera intestinale nella formazione di metastasi al fegato di tumori intestinali, a partire dall’ipotesi che il trasferimento di batteri possa favorire anche quello delle cellule tumorali”.