Impact of wheat bran physical properties and chemical composition on whole grain flour mixing and baking properties. Sviatoslav Navrotskyi, Gang Guo et al. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2019.102790

In evidenza:

Nel complesso, questo studio suggerisce una forte relazione tra proteine della crusca, ceneri, composti fenolici estraibili, capacità di ritenzione idrica e proprietà funzionali della farina integrale.

Nonostante i benefici per la salute dei cereali integrali, la crusca di frumento tende a diminuire la forza dell’impasto,la tolleranza alla miscelazione e alla fermentazione e a ridurre il volume del pane e la morbidezza della mollica (Gajula, 2007). Le proprietà negative della crusca di frumento sono il risultato delle interazioni tra i componenti della farina (principalmente glutine) e i componenti chimici della crusca, come fibre alimentari, composti fenolici, antiossidanti, composti sulfidrilici a basso peso molecolare ed enzimi (Khalid et al., 2017 , Noort et al., 2010), o proprietà fisiche della crusca, come la capacità di ritenzione idrica (WRC) e la dimensione delle particelle della crusca (Jacobs et al., 2015).

Gli antiossidanti possono interagire con le proteine del glutine riducendo le reazioni di interscambio disolfuro-solfidrile, influenzando così l’aggregazione delle proteine del glutine (Huang et al., 2018).

Le proprietà antiossidanti delle crusche di frumento sono determinate principalmente dal loro contenuto fenolico libero, legato e coniugato. Il ruolo di questi composti fenolici nella formazione della rete del glutine può essere spiegato dalla loro capacità di reagire con i gruppi solfidrilici delle proteine del glutine o di aumentare la velocità degli scambi proteici solfidril-disolfuro (Han e Koh, 2011).

Ad esempio, l’aggiunta di acidi fenolici al pane diminuisce il tempo di miscelazione, la tolleranza e l’elasticità dell’impasto e diminuisce il volume del pane (Han e Koh, 2011).

I composti sulfidrilici liberi, concentrati nella crusca e nel germe del chicco di grano, contribuiscono ad un notevole ammorbidimento dell’impasto (Noctor et al., 2012). Tra tutti i composti sulfidrilici a basso peso molecolare presenti nel chicco di grano, il glutatione è il più studiato. Il glutatione ha un effetto negativo sullo sviluppo della rete del glutine formando legami disolfuro con i residui di cisteina delle protein del glutine e interrompendo così la formazione dei macropolimeri del glutine (Noctor et al., 2012).

“Abstract

Wheat bran can have diverse chemical composition and physical properties. The objective of this study was to determine the associations among physical and chemical properties of bran and the mixing and baking properties of whole wheat flour. Eighty samples of bran were milled into fine (463 μm) and coarse (783 μm) particle size groups and analyzed for water retention capacity, protein, ash, lipoxygenase activity, antioxidant activity, sulfhydryl groups, and extractable phenolics. Brans were mixed with a single refined flour to make reconstituted whole wheat flour and analyzed for mixing and baking quality. Fine particle size samples had larger bread loaf volume, and softer bread texture compared to the coarse samples. Bran protein and extractable phenolics showed positive correlations with dough strength (p < 0.01) and development time (p < 0.01), respectively. Bran ash was positively correlated with dough strength (p = 0.004). Water retention capacity (WRC) of bran was significantly correlated with dough development time (p = 0.002), bread volume (p = 0.002) and initial hardness (p = 0.007) and firmness (p = 0.028). Overall, this study suggested a strong relationship between bran protein, ash, extractable phenolics, and water retention capacity and whole wheat flour functional properties.

Introduction

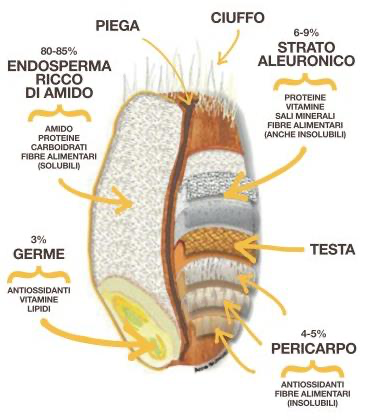

Whole grain foods are well known for their nutritional benefits (Hemdane et al., 2016a, Hemdane et al., 2016b). Epidemiological studies have shown that whole grain foods decrease the risk of type 2 diabetes, obesity, and heart disease (Cho et al., 2013) These benefits are likely derived from the combination of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and dietary fibers that are present in wheat bran.

Despite the health benefits of whole grains, wheat bran (i.e., non-flour components) tends to decrease dough strength and mixing and fermentation tolerance and reduce bread volume and crumb softness (Gajula, 2007). The negative properties of wheat bran are the result of interactions between flour components (mainly gluten) and either chemical components of the bran, such as dietary fibers, phenolics, antioxidants, low molecular weight sulfhydryl compounds, and enzymes (Khalid et al., 2017, Noort et al., 2010), or physical properties of the bran, such as water retention capacity (WRC) and bran particle size (Jacobs et al., 2015).

One of the main contributors to the poor functionality of the whole grain flour are dietary fibers. Dietary fibers generally result in reduced bread volume and poor texture (Mishra, 2016). The negative effects of dietary fibers on bread volume and texture can be by explained in many instances by the competition for water between these carbohydrate polymers and gluten proteins, which causes dough weakening (Rosell et al., 2010).

Antioxidants can interact with gluten proteins by reducing disulfide-sulfhydryl interchange reactions, thus impacting gluten protein aggregation (Huang et al., 2018).

Antioxidant properties of wheat brans are mainly determined by their free, bound and conjugated phenolic content. The role of these phenolic compounds in gluten network formation can be explained by their ability to react with gluten protein sulfhydryl groups or increase the rate of protein sulfhydryl-disulfide interchanges (Han and Koh, 2011).

For instance, the addition of phenolic acids to bread decreases dough mixing time, tolerance, and elasticity and decreases bread volume (Han and Koh, 2011).

Free sulfhydryl compounds, which are concentrated in the bran and germ of the wheat kernel, contribute to considerable dough softening (Noctor et al., 2012).

Among all low molecular weight sulfhydryl compounds present in the wheat kernel, glutathione is the most studied. Glutathione has a negative effect on gluten network development by forming disulfide bonds with cysteine residues of gluten proteins and thus terminating gluten macropolymer formation (Noctor et al., 2012).

Finally, bran-associated enzymes have variable effects on bread quality. For example, lipoxygenase (LOX) produces active peroxides that can oxidize glutenin thiol groups and promote gluten macropolymer formation (Bahal et al., 2013). However, LOX can impact the flavor of products by catalyzing hydroperoxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, which leads to the formation of grassy or beany off-flavors (Hemdane et al., 2016a, Hemdane et al., 2016b).

Bran composition varies among different wheat lines and growing environments (Hossain et al., 2013, Cai et al., 2014). Additionally, due to the different distribution of chemical components among the bran layers (Hemdane et al., 2016a, Hemdane et al., 2016b), milling performance can significantly influence the chemical composition of bran.

Furthermore, bran particle size also has a significant impact on bread quality (Xu et al., 2018), although contradicting results have been reported. de Kock et al. (1999) reported higher loaf volumes by utilizing coarse bran (1800 μm) compared to fine bran (750 μm), and Noort et al. (2010) showed a linear increase in loaf volume with an increase in bran particle size from 70 to 1000 μm.

Inoltre, anche la dimensione delle particelle di crusca ha un impatto significativo sulla qualità del pane (Xu et al., 2018), sebbene siano stati riportati risultati contraddittori. de Kock et al. (1999) hanno riportato volumi di pane più elevati utilizzando crusca grossolana (1800μm) rispetto alla crusca fine (750μm), e Noort et al. (2010) hanno mostrato un aumento lineare del volume del pane con un aumento della dimensione delle particelle di crusca da 70 a 1000μm

However, Zhang and Moore (1999) reported the largest loaf volumes for samples containing medium particle size bran (415 μm) compared with coarse (609 μm) and fine (278 μm). The conflicting reports could be explained by differences in chemical composition among brans, or by differences in milling and baking techniques used.

The present study was designed to identify the role of chemical and physical properties of wheat bran in the mixing and breadmaking quality of whole wheat flour. Chemical components that were most likely to influence flour functionality were selected, taking into consideration the number of samples analyzed. Ultimately, bran particle size, protein, ash, free sulfhydryl groups, extractable phenolics, antioxidant activity, LOX activity, and WRC were evaluated, with dietary fiber evaluated on a subset of samples (due to the laborious nature of dietary fiber analysis). Because we desired to examine the functionality of bran independently of endosperm properties, bran samples were combined with a single based flour to make reconstituted whole grain flours for mixing and baking tests.

Specifically, the coarse particle size brans had significantly higher WRC and lower antioxidant activity. Other chemical components were not significantly impacted by particle size of the bran.

The differences in WRC among bran particle size fractions may be explained by the enhanced ability of coarse particles to trap weakly bound water compared with fine particles.”